This article is about food. I promise. Just bear with me.

* * *

On being foreign

In January 2018, I went to Japan to visit my grandmother, who was ill and unlikely to recover. My mother had already flown out from Canada to be with her, and she suggested that if I wanted to see my grandmother before she died, I should visit soon. So I boarded a plane from my home in London, hoping I’d make it in time.

My grandmother, obaachan in Japanese, had been living in an old age home for several years, and over that time had developed dementia. Dementia is a serious business, but when I visited her two years earlier, I was surprised and delighted at how funny she found her situation. She would ask me if I had seen my uncle, and then laugh when I pointed out he was sitting right next to her. Her memory was like a goldfish. After asking and re-asking the same question five or six times, my uncle and I would point out the repetition. “Oh, did I already say that?” she’d chuckle… and then ask the question again with a smile. “If I live that long and get dementia,” I said to friends, “I hope I’m like her — she is so cheerful!” Her combination of ignorance and innocence defined her resilience. Every new revelation was a delight.

This visit was different. Late in 2017 my grandmother had caught pneumonia, and at 90-something, pneumonia is no small matter. When my uncle, cousin and I arrived at the home, she was sleeping. But after travelling from such a distance to see her, we ignored her need to sleep and tried to gain her attention. “Obaachan,” we said. “We’ve come to visit you.”

I wish we had just let her sleep. Waking up was such a struggle. It was selfish of us to demand it of her. Her eyelids were heavy and protested the movement. My uncle had to use his fingers to pry them open. Breathing while awake was more difficult than when asleep. Something (maybe everything?) was painful, but she couldn’t articulate what. Sitting up hurt. Laying back down was no relief. We plumped pillows, rubbed her arms and legs, and fed her juice, which caused her to choke. We fruitlessly tried to relieve her of her discomfort while actually causing her more. What was most distressing was just how confused she was. She didn’t know who we were, or why we were disturbing her rest. I stood back, seeing that the attention and touch of two people was already too much. “Koroshitekure.” “Please kill me.” These words she repeatedly called out, asking us to help release her from pain. Already terrified of old age, this moment cemented my fear. I am terrified to live so long.

My uncle tried his best to keep things light. Knowing I’d travelled far for this moment, he turned the attention to me. “Hana-chan is here to see you. Do you remember her?” My cousin had coaxed the motorized bed to a semi-seated position, and my grandmother along with it. Several moments passed for obaachan to recover from the pain of the transition. When she finally did, she looked up. Her eyes widened in alarm. Her arm raised in my direction and her finger extended out to point to me. “Mukou-no hito-da!” she exclaimed. “It’s a foreigner!”

* * *

On white-ness

I think it’s important to say early on (if it’s not already obvious from the above) that I “pass” as white. This has shaped the way that people see and treat me, and shaped the way I see myself. I’ve had all of the privileges that come with whiteness, as well as the exciting “exotic”-ness of being half-Japanese.

When I’m in Japan, I’m always praised for my language skills. People are surprised and delighted to hear fluent Japanese come out of my mouth. By contrast, when my brother is in Japan, his experience is the opposite. He looks Japanese, but when he opens his mouth and speaks his few heavily accented words, he is met with disappointment and confusion. We both confound Japanese people, but my looks have meant that I come off with the advantage.

It’s rare people recognize I’m multiracial. Looking back at this experience, I realize I have always had to tell people I’m part-Japanese and it’s the reason I chase my Japanese identity as hard as I do. I spend my free time cooking Japanese food, reading about it, developing Japanese recipes, and teaching others about Japanese dishes. I’ve always had to tell people that I’m Japanese, and I tend to do that with food.

* * *

On Japanese-ness

I grew up in Vancouver, Canada, with a Japanese mom and a German dad. My parents both immigrated to Canada in their early 20s. They met in Edmonton (of all places) and moved to Vancouver, where they were married and I was born. In Vancouver, my childhood activities were similar to many children who grew up with immigrant parents. I went to regular Canadian school during the day, Japanese school two evenings a week, and for a short time, German school on Saturdays. Other evenings were occupied by piano lessons and ballet.

My relationship with Japanese language school was not a happy one. Out of a school of roughly 300 children, only two of us (me and my oldest friend, Aki) were half-Japanese in an otherwise all ethnically Japanese student population. The other children all spoke Japanese at home, but Aki and I grew up using English, the lingua franca of our Japanese-German households. After about grade 3, we struggled to keep up with the other children, and I eventually checked out. I avoided homework, “forgot” my books when driving to school, and devised various ways to cheat on tests. (That is, until I got caught and was moved to the front of the classroom for my remaining two years at the school.) Aki didn’t seem to care — her confidence in herself didn’t rely on her ability to speak, read, or write Japanese — but I did. Each week’s Japanese school lesson was a reminder that I was less smart, less studious, and less Japanese than my peers. This was made abundantly clear each month, when our teacher would hand back tests in order of achievement. “Matsumomo-kun! 100%”, “Suzuki-san! 98%”… Aki and I alternated in receiving our test papers last, our scores dwindling from 60% in grade 4, down to about 30% in grade 6. At regular school, I was a high achiever, but at Japanese school I was a dud. I just wasn’t Japanese enough.

* * *

On food

One thing I was always good at, though, was eating. “She’s a good eater”, other parents would say. Perhaps it was a polite way of them letting my parents know I’d eaten their cupboards bare, but at the time I took pride in being a “good eater”. Eating, and later cooking, was something I could do well. I learned to cook by helping my mother, whose cooking repertoire would be one that many Japanese-Canadian families would recognize — sometimes Japanese, sometimes North American, and sometimes a mix of Japanese foods and “Canadian” foods in bizarre and delicious (and sometimes not so delicious) combinations. I enthusiastically learned as much as I could from her. Starting at around 11 years old, I was given the grown-up responsibility of preparing dinner for my dad, my brother, and myself when my mother was away working as a flight attendant. I revelled in the responsibility. It was both an hour of freedom at the end of the school day, as well as an indication that I was good enough at something to be trusted to do it on my own.

In my early twenties, I moved to Japan. Those three years were an education in Japanese culture through food and cooking as much as anything else. My background meant that I was far ahead of other expat colleagues in my knowledge of Japanese food, and my confidence in my Japanese identity grew. I started a recipe column in a local expat newsletter, teaching my peers how to navigate the grocery aisles and put together simple Japanese meals. And while I presented those recipes as an “expert”, they were opportunities to hone my own skills and learn more about Japanese food for myself. I shopped, cooked, and ate with real Japanese ingredients, ate out in real Japanese restaurants, and put each experience in contrast with the Japanese-Canadian food of my youth. In comparison to what I was eating in Japan, the North American-ness of Japanese food in Canada became apparent to me. Even my mother’s home cooking — with its larger pieces, larger portions, and foreign elements unabashedly mixed with traditional ones — expressed North American values of maximilization and multiculturalism. Over three years of study, I parsed what was “authentically” Japanese from what was other.

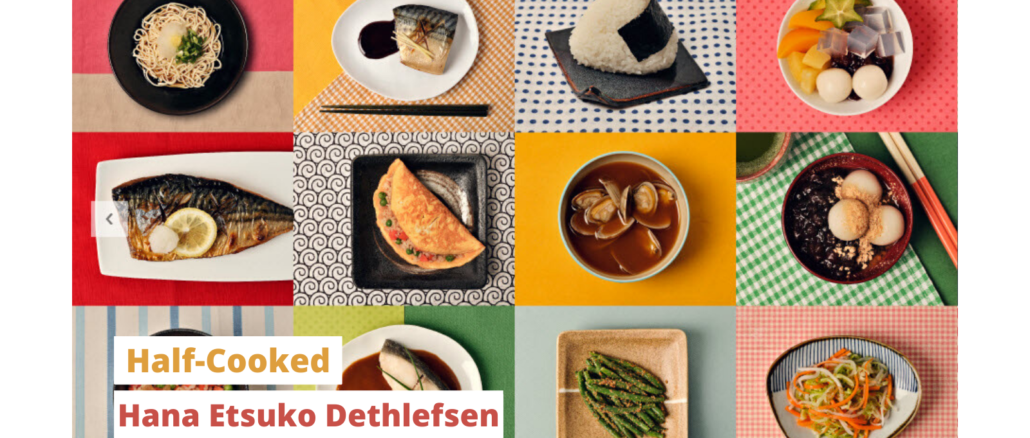

After returning to Canada, I started teaching a Japanese cooking class at the University of British Columbia. Through those lessons, I developed a set of recipes that I turned into my first cookbook, Let’s Cooking. I wanted to correct people’s perception of Japanese food and to share with people what real, authentic Japanese home cooking was. At the time, it was important to me that people knew that the sushi, ramen, and gyoza they ate in restaurants wasn’t Japanese daily fare. In developing my classes and book, I leapt into researching traditional Japanese food. I loved the research — loved learning more about the concepts behind traditional Japanese cooking, loved improving my skills in the kitchen, and loved sharing what I was learning with students.

In Let’s Cooking, I boiled down all of Japanese cooking (pardon the pun) to a simple set of main recipes and accompanying variations. Tidy. Easily approached. Practical. What was ostensibly a helpful way for home cooks to try out real Japanese cooking was also a helpful way for me to define for myself what was authentic Japanese cuisine and culture. A way to categorize what was Japanese, and what was not.

* * *

On TV

The book did better than I could have imagined. A crowd-funding campaign video and a couple of breakfast television spots later, I had a call from a television production company. Was I interested in auditioning for a cooking show?

I got the job and presented two seasons’ worth of shows. On the outside, I smiled, but internally I struggled. Although it was fun and I am thankful for the experience, the recipes I presented were not my own. For their own reasons, the television company held the intellectual property of the recipes and content. That meant I was cooking — on national television — Japanese recipes that had been chosen and developed by a white producer and a white chef, but presenting their recipes as my own, and as authentically Japanese.

Not all recipes were problematic, but when they were, there were often too many problems to fix in time for filming. I realized that if I was going to get Japanese food on national TV, I would have to pick my battles and compromise. Sure, there were some shows on TV that occasionally introduced Japanese recipes, but I had never before seen a Japanese cooking show outside of Japan. So I bit my lip on the small stuff and spoke out about only the major errors. Surely some presence on mainstream television was a start, right?

Through it all was a strong feeling of self-doubt. Whenever I did call out mistakes, I was always secretly worried — what if I was wrong? Here, on this television show, where I was being asked to represent Japanese cuisine, I couldn’t afford to make a mistake. It would prove that I wasn’t Japanese, or at least, Japanese enough. Before calling anything out, I would rigorously research to make sure I was correct. Being “half-Japanese” meant that there was a half of me that wasn’t. A half of me who might not know. That other half left room for me to think that others might know better than I did. The chef was professionally trained, after all, and I wasn’t. The TV producer certainly knew more about making TV than I did. Looking back, I see that I let too many things go. I gave others the authority to “know” more than I did, because I felt only “half” Japanese.

* * *

On being in-between

In 2016, I started the research for a new cookbook. After publishing Let’s Cooking, I had seen people really take up the recipe okonomiyaki — cabbage pancakes. Readers told me that they made them regularly, and that okonomiyaki had become a part of their repertoire. I was thrilled. And when I asked them why, they said, “because I already know how to make a pancake.” It hit me — hard. Like okonomiyaki, many other foods in Japan had similarities to Western food… because many Japanese foods originated in the West. I saw that there was an opportunity to point out the familiar in what is often seen as a prestigious, unobtainable cuisine.

I become obsessed. I wanted to know more about the origins of katsu-don (pork cutlet on rice), gyoza (pork dumplings), okonomiyaki, and ramen (noodle soup); foods that came to Japan from Europe, China, the U.S., and Korea. Cutlets, dumplings, pancakes, noodles — these were all foods that were familiar to my students and readers. I thought that if I could show them how similar these dishes were to food they already knew how to make, then these recipes could be their first baby-steps into Japanese cooking.

I travelled to Japan and spent days photographing menus. I went to resutoran-gai (restaurant streets) and painstakingly photographed every page of every menu on each street. After returning, I spend months translating and transcribing each item into a database, researching, cataloguing, and tagging each item’s country of origin. I wanted to know how many of the dishes offered in the restaurants were “Japanese”, but actually came from elsewhere. And when all of the data dust settled, my hunch was confirmed. Despite the “Japanese” appearance of the dishes listed, most of them were originally from the West or China.

I learned so many things through the research I did for this project, but the research that impacted me most was about dumplings. When I learned that Japanese gyoza and Chinese mantou, Turkish manti, and Italian ravioli might all be cousins related through the Silk Road, I was bowled over. It seems silly to say it, but the realization that Eurasian dumplings were related to one another released me from my obsession of categorise and label dishes, and the need to categorise myself. None of these dumplings could fully be attributed to the ownership of any one culture. If dumplings could be both European and Asian, then why couldn’t I?

What I set about to do with this project was to point out the familiar elements of Japanese food. But what I ended up asking was “Is it possible to be both from somewhere else and be Japanese”? It was truly a revelation to realize that all of the cooking, recipe development, and research into Japanese cooking was about understanding who I am. And what it means to be Japanese. Or not Japanese. Or in-between.

* * *

On language

Words do funny things, don’t they? The word “half”, for example, both includes and excludes.

I describe myself as “half-” in many ways. The most obvious is in my cultural heritage, but in my early 30s I started to call myself “half-deaf”. I suffered from sudden hearing loss and wear one hearing aid. Soon after receiving it, I was invited to a professional networking event for the deaf and hard of hearing, where I soon realized that my experience was not at all that of someone with profound hearing loss. I realized I could not claim the identity of deafness.

In my mid-30s I received dual citizenship with Germany, and used my EU passport to move to the UK. It made me feel as though I could finally legitimately call myself “half-German”… that is until I tried to get through customs in Germany. When the customs officer realized I couldn’t speak German, he let me know in no uncertain terms that I had no claim on German-ness.

I’ve grown up calling myself “half-Japanese”, and never really questioning that “half” defined me only as a part of a whole. For a while in Japan there was a push to call people like me “double” (daburu) instead of “half” (ha-fu), to acknowledge that we have dual identity instead of half of one. But the word “double” hasn’t stuck, and I continue to use “half-” to describe my Japanese-ness. I don’t look very Japanese, and people don’t treat me like I am, so what right do I have to claim Japanese-ness? My Japanese language is functional, but not awesome, so although I say I am fluent, it isn’t “native” (or sometimes even very fluent). And although I’ve spent a lot of time in Japan, I’m not up to date on all of the current trends. Despite my ambition to claim all of my identities, when it comes to Japaneseness, “half” still feels like the right descriptor to me.

“Half”. It means I’m a part of something, but never fully.

* * *

Katsu-don

This recipe is for a pork schnitzel on rice. I like to think of it as the culinary equivalent of me. A German schnitzel on a bed of Japanese rice adorned with hanjuku (half-cooked) egg cooked in a sweetened soy-flavoured broth. German. Japanese. Half(-cooked). If I ever do anything special enough to warrant a biography, I want it to be called Schnitzel on Rice.

The key to this dish is timing, as you want to have all of the elements complete at the same time. My instructions walk you through the multi-tasking, but the most important thing is to ensure is that you have nothing else on the go when it’s time to cook the eggs, which should be removed from heat before you think they should be. Hanjuku eggs will be luscious and soft.

Time: 45 mins – 1 hr

Makes: 4 mains

Ingredients:

4 cups hot, cooked Japanese rice

A

4 pieces (approx. 500g) pork loin

salt & pepper

¼ cup flour

1 – 2 eggs, beaten

1 cup panko breadcrumbs

vegetable oil for frying

B

3 cups water

2 tsp dashi powder

2 Tbsp soy sauce

2 Tbsp mirin

2 Tbsp sugar

1 medium onion, sliced thinly

4 green onion, sliced into 2 inch lengths

8 eggs, beaten

Garnish:

thinly sliced green onion

shichimi 7-spice or ground sansho pepper

Tip: Serve your katsudon with both chopsticks and a spoon — the chopsticks for the tonkatsu, and a spoon to scoop up soft, eggy rice.

- Put the rice on to cook while you make everything else. Having hot rice on hand at the moment of assembly is critical, so put the rice on to cook. If you have a rice cooker, this will be the time to use it, as you’ll have plenty of other things on the go. If not, keep the lid on once done to keep it piping hot.

- Prep & bread the tonkatsu (pork cutlets).

- Flatten the meat. Using a meat tenderizer, rolling pin, or even the bottom of a heavy cast iron pan, flatten the pork loin to about 4 – 5 mm thickness. Season with salt and pepper and set aside.

- Bread the meat. Prepare 3 shallow bowls with the flour, beaten egg, and panko breadcrumbs. Bread the meat by first coating it in flour, making sure to cover all surfaces. Shake off the excess, dip and cover with the egg, and then place into the breadcrumbs, pressing them in to ensure they stick to the meat. Set aside on a large platter.

- Cook the onions in the broth while the oil heats. Pour about ¾” – 1” of vegetable oil into a large, heavy bottomed pan (preferably cast iron). Heat on medium high heat. In another large saucepan, bring all of B to a boil, then reduce to a simmer and cook on low for about 10 – 15 minutes while you fry the cutlets.

- Fry the cutlets while the onions cook. Test the oil to see if it’s hot enough by dropping a nib of eggy breadcrumbs in. If it sinks partway and then floats back up, it’s the right temperature. If it sinks, it’s not hot enough, and if it skits on the top of the oil, it’s too hot. Fry one or two at a time for about 3 – 4 minutes per side until a deep golden brown and crisp. Drain on a cooling rack or on plenty of paper towel and fry up the next batch.

- Rest the cutlets while you cook the eggs in the broth. When all the cutlets are fried and resting, bring up the heat on the broth, and when at a strong boil, drop the beaten egg into the middle of the hot broth. Don’t stir the egg. Instead, gently spoon some of the hot broth from the edge of the pan into the middle to heat the centre of the egg, watching carefully to pull the pan off the heat when the egg is only just halfway set. This should only take 1 – 2 minutes.

- Assemble. Work quickly to assemble the donburi rice bowls to ensure the egg is still soft, loose, and jiggly when served. Scoop rice into four serving bowls. Slice the tonkatsu on the bias into strips approx. 1.5 – 2 cm wide and place on top of the rice. Scoop and pour ¼ of the eggy broth over each bowl and garnish with some more sliced green onion.

Hana Etsuko Dethlefsen is half-Japanese, half-German, and grew up in Vancouver, Canada. She’s taught Japanese cooking in Vancouver and on TV, and now lives in London, England, where she is writing her second cookbook and posting @letscookingbook