When I was barely old enough to remember, my folks took me to a small suburban house in the Los Angeles megalopolis. In their backyard was a little pond, probably not more than a few hundred gallons in size. There were lots of aquatic plants in it, and, most beguiling to my nascent consciousness, there were guppies in the pond. I had recently discovered tropical fish and I had a little tank in my room at home with a few guppies. I thought that it was amazing, this backyard fishpond. I fell in love at that moment with all the possibilities of fish. When you are little and close to the ground, you see things differently. I have never really stopped seeing things differently. Lately I have decided to do something about it. I am building a place to completely immerse myself into the world of fish.

I had a moment around that time of life where the realization that I was going to die hit me like a brick in the back of the head. I was looking out the window of our blue 1957 Ford wagon at the yards lining San Roque Road, which was the street I grew up on. I don’t know if this happens to everyone. I was three. Later that day I told my mom I was going to live forever, and she gave me a bit of adult, saying, “Oh, and how are you going to do that?” We had a bougainvillea that covered the entrance to the back door that covered the first few years of my life with paper red flowers and I’ll not forget thinking this thought in their warm rose haze: “Ah, I am going to live forever.” Is that normal or common? I assume it is.

My mother was abandoned by her birth parents, along with her little sister when she was 4 years old. They left the two of them in a hotel room with some bread and some milk. A local woman sheriff found them and this being the 1920s, adopted the two girls herself. Grandma Thomas, as I knew her, liked to gamble and I remember her having me pull the 5-cent slot machine handles in Carson City, Nevada, when I was around 5. Even after security came and shooed me away from the machines, she waved me back to pull the handle. She gave me the cup of her nickel winnings at the hotel room, the Caesars Palace branded cup full and heavy.

For almost all my mother’s life she denied she had a little brother. Her younger sister had always claimed they did, but I never really heard her make this claim. One day when I was in my thirties with kids of my own, she asked me if I thought it was possible she did. She had received a letter from the IRS from a man claiming to be her half-brother. He laid out the family tree. He confirmed my mother’s little sister’s story. I wasn’t initially struck by the name but in retrospect it has become something of an organizing principle in my own life. Not simply that his name and my name are the same and spelled the same. More importantly that the moment I was named, she was denying she had a brother with the same name she decided to give me.

Loss and return seem to be the skeleton, their twinning girders the architecture of my life.

My dad grew up on a dairy farm. It was not my grandfather’s first choice, to be a dairy farmer. His first choice was to live in a commune. A collective. He was a follower of Eugene V. Debs and he believed in the idea from each according to the ability, to each according to their need. Debs ran for the presidency four times, the last time from jail in 1920. My grandfather and some other followers of Debs decided to start a commune in the town of Llano. It was essentially a disaster. Some people refused to do their fair share you might say. He had a brother who told him about some land in Lakeview, Oregon, so he went north and threw in with his brother. My dad was born there, and as the third boy and the seventh child he was given a name that started with E like his brothers Eric and Elmer. My dad’s name is Eugene.

I never met my grandfather. The most interesting thing I can say about him, besides his being a socialist, was that he started a school in Lakeview for all the children and that every one of his kids got a scholarship from a rich, local benefactor and went to college. Except my dad. The Peterson kids always won the scholarship and I guess it was decided that maybe somebody else should get to go to college. He graduated high school and went to work in a bank. After a couple years he moved in with his older brother Eric at Purdue and enrolled. He paid tuition once. By maintaining a 4.00 grade point average, he had his tuition reimbursed each semester he was there. Then he went to Caltech, where he said he met really smart students.

It only recently occurs to me that I too worked at a bank, although I worked there for 25 years and did no actual banking. I was a historian trying to find a way to align the past with the desires of people who think mostly of shareholder value and ROI. What I got out of the experience is a well-versed loathing of what counts as normalcy amongst the managers of capital in 21st-century United States of America. When I look at what counts as normalcy in people’s imagination as they buy stuff to surround themselves with in their manufactured suburban oasis, my loathing shifts. If you listen closely, I can bring you to my level. Or you can continue to make trips to Home Depot for Satan.

In my fantasy I am floating in my backyard pool, which is filled with hundreds of Cyprichromis. These little cichlids are open water mouthbreeders from the Rift Valley of Africa. The males of one common species are royal blue with sunflower yellow tails. The females school together, brooding their fry with stretched throats, eyeballs like marbles peering out through translucent skin in their buccal cavities. As I watch them, the females en masse, release their fry into the long, black roots of the water hyacinths, dangling beneath the surface. Hundreds of fry from dozens of mothers gather and dissipate in a syncopated rhythm, sunlight striping the green haze and lighting up individual fish with flashes of iridescence. As I drift, new miniatures of Lake Tanganyika fauna, Julidochromis and their polyamorous communities of adults and fry huddle and dart through lava rocks on the floor of the pond, looking like checkboard torpedoes. Since it’s my fantasy, I see a sandy bottom with any number of sand spawning jewels, males staking out territories to entice reproduction. It’s something I have thought about for years.

2017, my corporate position at a bank was eliminated after working there since 1992. I was relieved. I thought I didn’t hate my job, but it became apparent, for at least a decade really, that I was working for cheerleaders and jocks. High school Rockefellers, dinosaurs of American atavism. I got close enough to see their glistening maw, the sinews of fresh kills stuck in their gleaming white teeth. I had watched these carnivores chew up the grasslands of a well-planted history, 3700% more company in the last 20 years. I went from guarding a legacy to defending its existence. The goal became “more white space” in the marketing lexicon. The soul of the company was streamlined and polished like the yards of my rich neighbors whose idea of nature is curb appeal and increased sale price. One neighbor monthly sprays branded carcinogens around his yard along with weed killer in his happy suburban production of Operation Ranch Hand. Vietnam is never far away in the minds of the ruling whites. Eliminate the gook bugs, build sterile spaces to raise offspring with immune deficiencies.

Corporations have metastasized and homes have grown even as the impossibility of unlimited growth heads like a meteor toward our collective future. I worked for my overlords and they paid me just enough to buy my way into a nice neighborhood lacking diversity. My wife grew up poor enough that she remembers the family recycling, hoping to collect enough to buy dinner. We had dreams of a property with a straw bale house on forty acres of chaparral and ended up back near the university where we met. We had lost our first child, a cadence of doom that this new old house in an uncrowded neighborhood seemed to change into a happy rave-up for raising our two young children. We had bought our simulacrum of Eden. We lay in our upstairs bedroom looking out over the pool at a backyard hillside covered in green. We would wake up thinking, “Can we afford this?” as though we had won a misplaced prize.

25 years later without a job, I found time to actually build my lunatic Eden.

Southern California is full of folks trying to attach a suburban Eden to an America heaven, with the latter provided by the winning climate. And there are a lot of pools in the locals’ attempts to build their personal version of nirvana amongst the native chaparral and invasive Eucalyptus forests that mark the ecology of their southern California house farms. Pools are poisoned deserts, chemically sterilized so that the kids can swim in them, the parents can drink in them, and the government can collect property taxes from their owners who hire men with long poles and bottles of acid and chlorine to keep their Edens pure. They are generally abandoned after the kids are gone.

For me, I wonder if my ideas of a perfect backyard can connect to something a bit more edifying than a blue desert. There are historical precedents for the Eden I am imagining. I think it is an inhabitable space. I don’t think Eden is a fortress. Somewhere toward the end of my career I got prostate cancer. I don’t want to minimize that or maximize it either. Cancer has a focusing power that cannot be avoided in our society. When you get a diagnosis, it sounds like “Luke, I am your father.” Prostate cancer is something most men get and relatively few die from. But it sits there, not only in the mind of the patient but in the minds of all who love the patient.

I was diagnosed in 2015. After the prostatectomy failed, there was radiation. My sex life disappeared mostly. Then, in late 2016, I was laid off. Finally, my dream seemed to be worthy of attention.

The essence of our modern world is consumption. Eat the apple. There was a moment when this was an agrarian country. It was no Eden, but it had more of at least one element. The psychological bridge between producers and consumers was crossed. We are now overwhelmingly consumers. Can becoming a producer open something up inside me, I wondered? Watching things grow and reproduce does something to me. I am becoming convinced it is where sanity lies … in reproducing. Cancer is insane reproduction. I wanted sane reproduction.

Eden should be something that can appear anywhere; that is, it should be affordable. I have always been taken by miniatures, dioramas of imaginary Eden or projection from the minds of people who hold the divine in their head buckets. Now, you can’t live in a diorama, but you can imagine the reality of being in one for a moment and the tingle is real to me anyway. People in the West tend to live in houses if they get half a chance and those houses are for less or for more their Eden. They spend most of their moments not spent under their overlord’s gaze in their fantasy space. They pay more to own the house they live in than anything else, except for maybe cancer treatment if they get that diagnosis. And often the house turns on them. The snake preaches debt in our neighborhood. A friend once said, “The sooner you get in debt, the sooner you get ahead.” Judging by the debts I have collected in the last 20 years, he was clearly my unconscious avatar.

If you bought a house in Levittown—the most famous of the first house farms that appeared after World War II—you received a box that was simplified Eden. Eden is about having a place to have sex as much as anything else, and pools and spas are linked to carnal delights. But there were no pools in these first developments. The pools were shared, community spaces.

Where I grew up on San Roque Road, shared elements with Levittown that surprised me when I looked at pictures of life there. Their everyday looked pretty similar to my everyday as a child. Every day I rode my Schwinn Fastback on streets that led to other kitchens decorated with wallpaper and Formica. Birthdays were a trip to the local roller rink. One of my best friend’s had a pool. I spent one entire summer going to his house every day to swim.

Community pride in Levittown seems to be measured by the size of the firehouse. In Santa Barbara, the highlight of the summer was fireworks at La Playa stadium. Before the show, every different type of firetruck operating in the area was lined up on the track. All the sirens were turned on as they circled, and the kids delighted in the cacophony.

Pools were rare, and they tended to be shared. Only the rich had pools, or at least kids who had pools in their backyard’s had been born into a rarified stratum that put Huck Finn into actual play. My preschool taught swimming, and swimming over the deep end was a psychological barrier that I accomplished the year after potty training. That’s not quite right, I just remember that somewhere around four or five the miracles of public daycare pissing were replaced with the new magical joys of pools.

Swimming training was something on the mind of my mother, who around this time had taken me along to have lunch at the boss’s house in the hills above Montecito. Their home was perched above the pool, a long set of steps led down to the turquoise waters. There was a step in the pool with maybe 18 inches of water over it. One fine day I was put in the pool and told to remain on this shallow ledge. I was left there with my life jacket while Mom went up the steps out of sight to the terrace above. I stepped off the ledge and began drowning within a few minutes and Ricky the German Sheppard saved me by barking that I was no longer where I was supposed to be on that ledge. I was told years later that Ricky was usually in charge of alerting them to my needs. I was often left in a carriage and when I awoke crying on that Montecito terrace, he would start woofing, “The human puppy is awake.” My dad was against us having a dog, but my mom ended up getting us a Sheltie.

To my mind now, pools are Aryan fantasy ponds. And while I have kept scads of fish tanks in every house I have owned, the urge to get right in there with them has been regulated to those trips to Hawaii when we snorkel with saltwater fish. I don’t keep fish because I want a showy jewel box; I keep them because the tank is a complete world to be immersed in as you try to mimic the wild in a way that fosters reproduction in your charges.

When the day came that I became a pool owner, I began to have a particular fantasy about doing something radical to my pool.

Lake Tanganyika is in the Rift Valley of Africa. The lakes are so deep that beyond a certain point, there is no oxygen. The bacteria that live below are anaerobic. Occasionally there is volcanic activity under the lake and a huge bubble of hydrogen sulfide erupts from the deep. This can cause mass casualties as the gases are heavier than the atmosphere and as it spreads over the human landscape surrounding the lake it displaces breathable air. People suffocate. Besides that, Lake Tanganyika is the home to my favorite fish, specifically those from the genus Cyprichromis. Lake Malawi is not bad either, and Lake Victoria is pretty interesting. The lake cichlids of these waters are incredibly diverse and complex. They are in nearly every fish store in America, Europe, Japan, etc. When I was about eight, the owner of Pet Manor, Mr. Redding, introduced me to Julidochromis Marleri. I have kept some sort of species of Julidochromis continuously, with only a few breaks, since 1969.

I imagine all aquarists fantasize about turning their pools into ponds at some point.

For nearly 20 years I suggested to my life partner that we go feral. At first it was “but what about the children?” Monthly pool fees went from 55 to 75 to 125 over the years and it remained a blue pit. The pool guy became enamored with my first Border Collie and we paid for all kinds of repairs to keep the thing clear, as the surest sign your alcoholism is catching up with you is either an unkempt lawn or a green pool.

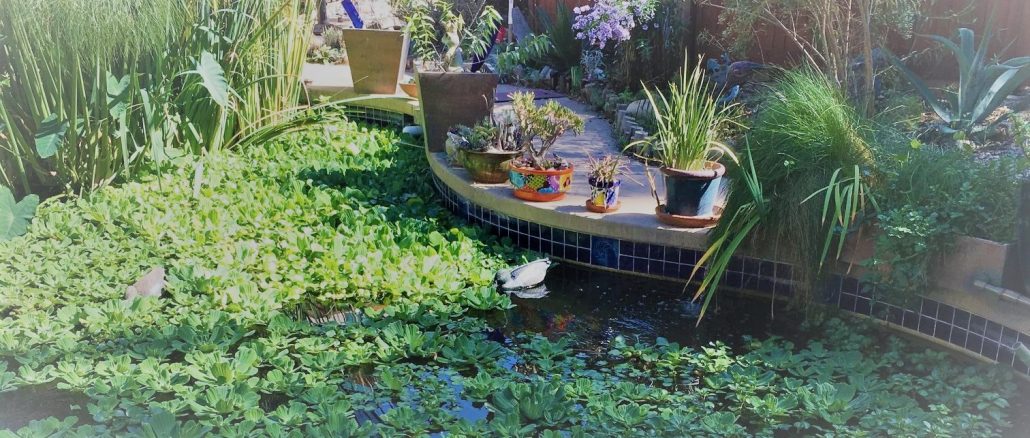

About the time I lost my corporate career my partner relented, and I was off to the races. What won her over was visiting another couple who had turned their pool into a giant koi pond filled with so many aquatic plants and animals that it fairly screams “fecund!” Listening to them and what challenges they had faced helped me to think about what I wanted to build, how I wanted to stage this space so that it was more Sunset and less hippie park.

I admit that a big part of my motivation at first was monetary, or at least anti-social. I hate that my neighbors abuse their ecological privilege to protect their investments rather than create habitat for all the animals displaced by their homes. I get it, we are all sinners here but spraying poison monthly around your yard is grounds for a drive by. If a weed killer commercial comes on the TV, I go nuts. If you don’t know that Roundup is going to be sued out of existence, to paraphrase Thoreau in jail, why don’t you? What is so wrong with folks that they can’t connect how they view their yards with how they view say, racism? What makes killing OK? Have you ever really asked yourself that question about anything besides humans?

I had an interesting conversation with a friend about buying property the other day. And after much triangulation and contextualization, he convinced me that mortgages are often the results of a lot of boat salesmen. Oh sure, you need a place to live, etc., but where is it written that indebtedness is a great freedom? That buddy who told me years ago that the sooner you get into debt, the sooner you get ahead? By that standard I have done well. I could have done a lot better just being disciplined with money. Too late for that now, and I am off to make my backyard a scary place for realtors.

The skin I have in the game now is considerable, although everything I have done so far is reversible. When I built the deck over the end of the pool, I used screws. I like to live in a way that makes me think I can unscrew myself. I built the greenhouse that sits on top of the deck over the pool-pond with the same philosophy in place. You could walk into a thousand—heck, ten thousand—backyards in San Diego and you will not see a single one that has my configuration.

Looking over the evolutionary construction, the mirrors tying it to my consciousness reflect back to me with surprising impact. Good intuition will echo truths back to you, the spooky result of the holographic paradigm. My dad is a physicist, a pragmatic one rather that a theoretical one, but one who studies fundamental truths about nature. A characteristic of holograms is that if you break off a piece, it contains the image from which it was separated. Whether that means that because he was a farmer I can’t escape the idea of turning my pool into a backyard fish farm or whether it means that the first humans (Adam and Eve anyone?) came from the same part of the world Cyprichromis come from or whether it means that in our attempt to control our world it refuses us, I don’t know.

We as a nation are in a liminal space, a moment of transition into either something horrible and neo-apocalyptic or something fascinating and neo-idyllic. We either face the future honestly and realize that Western capitalism is a collection of false promises made up by racists, or we worship at the feet of the titans of capitalism and lick the boots of death born out of fear. I hear that a lot of millennials are making work their god, not knowing, of course, that capital is the god they serve. They were told that good intentions are enough. Work hard, conform, win prizes. The prize most often displayed is a vacation to a place you can swim with colorful fish. And we are destroying it to visit it. I think I have a better idea. Time will tell.

As my wife and I walked through the neighborhood a few nights ago, I was struck by the waste and artifice that rules this community. During the day the place empties out, and few venture out except when the local schools open and close. It was dusk, so a few folks were out, and as we walked down our shared street she remarked to one of our neighbors, “Your yard looks nice.” We have watched him tear every plant out of his front yard, put in in a new walkway, and add mulch and a few ornamental plants. “It must have taken a lot of work,” and his expression suggested that she was right. I kept my mouth shut for a few houses. I agreed, but felt the question he answered was really not his; it was a question of property values not life values.

I had recently substituted at the local high school. They have an aquaponics club. At the moment, they are spending millions in bond money to build a fancy auditorium, a gym, new athletic fields god knows what. Public schools are in competition with private schools for students, students they will track into fancy universities, creating engineers to make digital products for massive corporations who worship the black mirror. Kids will be able to code but they won’t be able to grow a garden. They will outsource the production of the calories they consume to people far away who they either abhor or ignore. I feel like I am at the epicenter of stupidity.

“What if,” I began talking to my wife, “there was a program teaching urban farming at the high school? And the kids grew vegetables in the yards of these folks instead of then creating another ecologically dead curb appealing ornamentation . . . .” I went on and on. She didn’t say too much. Most people don’t. They aren’t scared enough yet.

I’m scared. I’ll be dead soon enough and most of the hell coming will take place on top of my grave. Everyone eventually stops being a consumer. I just thought I might try to do it while I was alive.

Irascible and profane, ALLAN PETERSON was born and raised in Santa Barbara, California, moved to San Diego for college, married a local girl, and sealed his fate. A recovering corporate drone, he seeks to repent his banal ways and pursue sustainable fantasies of exotic flora and fauna. With two grown children out of the house, he lives with his wife Janet of 33 years, two irresistible border collies, and a whole lot of fish.

Irascible and profane, ALLAN PETERSON was born and raised in Santa Barbara, California, moved to San Diego for college, married a local girl, and sealed his fate. A recovering corporate drone, he seeks to repent his banal ways and pursue sustainable fantasies of exotic flora and fauna. With two grown children out of the house, he lives with his wife Janet of 33 years, two irresistible border collies, and a whole lot of fish.