“Shver tsu Zayn a Yid” follows a young anthropologist discovering his own ethnic identity as a Jew. The process was made difficult—potentially dangerous at times—by ‘background’ anti-Semitism exacerbated by Israeli government abuse of Palestinians, and by his family’s penchant for secret-keeping stretching back five-hundred years.

It’s “Hard to Be a Jew.” Being a Jew in the Diaspora (we call it exile), has always been dodgy: dishonest and dangerous both. When anti-Semitism comes to the table, you anticipate insults, maybe worse. You dissemble.

In the ‘80s, I played poker with a bunch of guys in San Diego. When one in particular was absent—a man with an obviously Jewish phiz, family name and New York accent—he was mocked without mercy.

“Would you rather have a thousand dollars, or Weintraub’s nose stuffed with nickels?”

“If I had his nose stuffed with that much money, I wouldn’t be playing cards with you cheap bastards.”

I stayed shtum: I call it “passing for Goy.” If they didn’t remember I was Jewish too, I wasn’t going to remind them. We were all social scientists, most anthropologists. Who should have been more “woke”?

The founding of the modern State of Israel was supposed to make this all go away. Partly in self-mockery, Yiddish-speaking European Jews used to inquire of any incoming news: “Iz es git fur der Yidden oder iz es shlecht fur der Yidden?” (‘Is it good for the Jews or is it bad for the Jews?’) We’re now obliged to ask of any news about Israel (as Israel’s neighbors constantly must): “Is Israel good for us or, is Israel bad for us?” Sadly, the answers too often tilt towards the latter. This further complicates existence for virtually all Jews, no matter how we might feel about Israel’s government. The dream of Israel was to defend Diaspora Jews from anti-Semitism. Instead, the Israeli government foments anti-Semitism by criminally displacing and abusing Palestinians, using the Diaspora as cover. I don’t know if in principle the Israeli state is good or bad for the Jews, but it doesn’t make it any easier to be one.

My family’s secret-keeping (they kept more secrets than the Secret Service), meant my fuzzed-up identity had already been founded on sand. Most of their secrets were pretty mundane—the philosopher Hannah Arendt had it wrong: evil is evil; it’s embarrassment that’s banal—but a few were existential.

My mother grew younger by the decade. In the 1920 census, her birth year was given as 1910, in 1930 as 1911, in 1940 as 1912. Growing up, my brother and I had been told she’d been born in 1913, allowing her to claim to be three years younger than our father. While looking for papers of my own in 1967, I found my mother’s 1910 birth certificate. It was amazing to her sister’s sons that my brother and I hadn’t known this.

Those same papers informed me that, before marrying our mother in 1947, our father had been married to a servicewoman during WW II. His older brother—who’d played pater familias in the U.S. until permanently promoted by the Nazi murder of our Polish family—disapproved of the marriage and forced my father to have it annulled. At least part of the reason their younger sister settled with her husband in California after the War was to escape her New York brothers’ control! Her father had behaved much the same; she’d had enough!

Other family secrets directly affected my identity as a Jew. As a youth growing up in Poland, my father had been a member of Mizrachi, the religious Zionist movement. (The movement name is a contraction of Merkaz Ruchani ‘Spirit Center,’ but the Hebrew word mizrach means ‘east’; mizrachi Jews dwelt in and around the Holy Land.) My father was supposed to emigrate to the Yeshuv, the Jewish ‘Settlement’ in Palestine that preceded the establishment of an Israeli state. His expected visa went to someone with better political connections; he was sent to join his older brother in America. His enduring resentment helps explain how I came to grow up in a post-World War II Jewish home with almost no feeling about Israel: apart from the Passover holiday, the name was hardly spoken in our house.

When I went to be divorced, though, my sense of Jewish identity was totally upended. I learned I was not Ashkenazi—as I’d believed my entire life—I was Sephardi!

If you’re not Jewish, those last sentences probably won’t mean anything at all. If you are Jewish, you will be scratching your head even more vigorously—how could a person be confused about something so basic? Central and Eastern European Ashkenazim dine on borscht (beet soup), gehakte leber (chopped chicken liver mixed with chicken fat, onion and eggs) and blintzes (cheese or fruit stuffed unleavened pancakes). Circum-Mediterranean Sephardim, on the other hand, relish garbanzos (chick peas), lamb tagine (stewed with fruits and nuts in a greased earthenware pot) and dolmos (lentil- and rice-stuffed grape leaves). How could a person not know what he’d had for dinner?

I got my first ‘non-Sunday School’ lessons in ancient Jewish history from an ancient Czech Jew on an Israeli kibbutz near Petah Tikva. Polyshook (if he had another name, I never heard it) had roamed Central Europe as an itinerant printer either side of WWI: his itinerancy due in large measure to his penchant for printing communist and anarchist broadsides. I appeared to be the only young man on the kibbutz interested in hearing his stories … and sharing the fierce banana liqueur he made from the over-ripe fruit we banana cultivators brought him.

“The Jews had been making bezrodnyi cosmopolitov (Russian: ‘rootless cosmopolitans’) of themselves in Greece and Rome for five centuries before the final revolt against the Roman Okupace (Czech: ‘Occupation’),” Polyshook said. “That balagan (Yiddish: ‘mess’) ended at Masada in 136 AD.” (I gave up counting how many languages the old man spoke.)

“I was taught that Bar Kochba and his men refused to surrender. That they killed their wives and children before taking their own lives.”

“True, they were kashe oref (‘stiff-necked’),” he said in the Biblical phrase, “but I‘ve always wondered if the ferkakte (‘crapped up’) Romans didn’t slaughter everyone, then blame it on the Jews. History’s first documented case of ley fuego—‘shot while attempting to escape,’ eh?” Polyshook added with a raised eyebrow.

“In any case,” he went on, “Judea was all but depopulated. The Jews who escaped deportation to slavery in Rome scattered in every direction: throughout Asia as far as Kazakhstan, India and the Yemen; to Europe, where they melded with the earlier settlers to become the Sephardim and Ashkenazim.”

Traveling with the Islamic conquest, Polyshook explained, the Sephardim (from Sfarad, classical Hebrew for Iberia), reached Spain via North Africa in the 7th and 8th centuries AD. Meanwhile, the Ashkenazim—named for an imaginary kingdom that took its appellation from Ashkenaz, a great-grandson of Noah—migrated into Central Europe via the Levant and the Caucuses, dragging the Kingdom of Ashkenaz behind them from Scythia, through the Slavic lands, eventually to the Rhineland: Ashkenaz is now Hebrew for Germany.

“Because the Ashkenazim were influenced by the languages and customs of the Slavs and Germans,” Polyshook said, “and Sephardi culture shaped by that of Arabs, Berbers and Iberians, each developed distinct farstelung (‘practices, conceptions’), even very different ideas of how it was to be a Jew.”

“With each convinced that the other had gotten it completely wrong. My father used to say: ‘Ask a question of two Jews, and you’ll get three [strongly held] opinions.’”

“Still,” Polyshook said, “both continued to write with Hebrew otot (‘letters’), to be influenced by Hebrew dikduk (‘grammar’) and to govern themselves under Halacha (traditional Jewish law). Hebrew itself was set aside as the lashon ha-kodesh (‘holy tongue’), reserved for ritual and scholarship.”

As an anthropological linguist, I knew the Sephardim had elaborated a secular language—variously called Ladino, Espanyol, or Judió—from a Hebrew and Arabic inflected Old Spanish. Meanwhile, between the mid-11th and mid-14th centuries, the Ashkenazim developed Yiddish from the extant Middle High German, informing it with Hebrew, Aramaic, Slavic and even French and Latin—the Yiddish for ‘bless,’ bentshen, comes from the same root as benediction. In consequence, Sephardim call their fathers padre; Ashkenazim call theirs by the Slavic tateh. Surely a person knows what he calls his father.

Still, as I was about to learn from my own father, it wasn’t that simple.

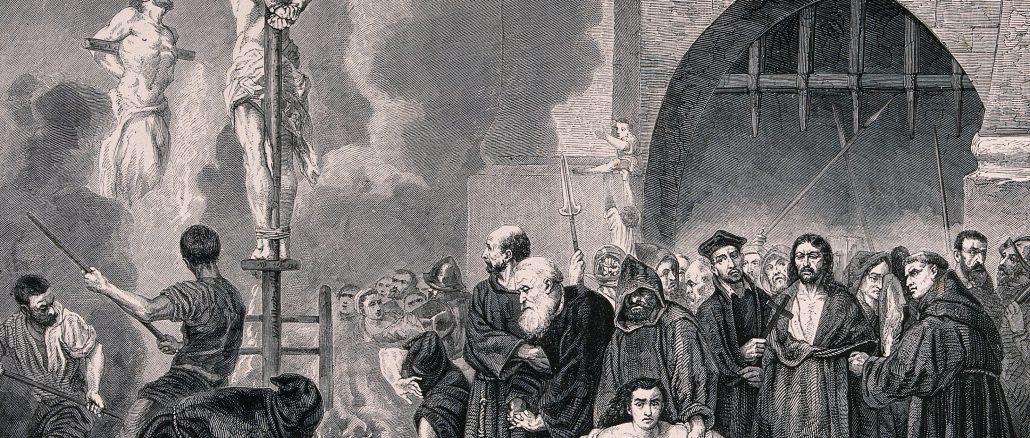

“When the Spanish finished wiping out the Muselmanehs (he meant the Moors), they turned on the Jews,” he said. “The Inqvizitsia (‘Inquisition’) murdered or scared plenty of Jews into becoming afikorsim (abandoners of their faith)—at least in public. But that wasn’t enough for the king and queen [Ferdinand and Isabella]. They ordered a geroosh (‘expulsion’) of the Jews and many Naiyeh Kristinehs (‘New Christians’) accused of being ‘secret Jews’ [called marranos in Spanish] went with them.”

(Support for the idea Columbus might have been Jewish comes from his 1492 diary, which begins: “In the same month in which their Majesties issued the edict that all Jews should be driven from the kingdom … they gave me the order to undertake with sufficient men my expedition of discovery to the Indies.” It suggests the expulsion was that notable to him.)

“Where did the expelled Jews go, Papa?”

“I always heard the most went back to the Mahgreb (‘Northwest Africa’),” he said, “or, east towards Turkey. Others ran away to places where the Inqvizitsia wasn’t so strict: the Felachlanden (‘Lowlands’) that became Belgium and Holland; the colonies in Brazil and the Caribbean.” (A Brazilian friend suspects his ancestors were marranos: no one in the family claimed to be Jewish, but his grandmother followed otherwise inexplicable customs, like lighting candles at twilight on Fridays.)

Of the Sephardim who settled in Northern Europe, some continued east, into Germany and thence, by invitation to Poland, where they assimilated into existing Ashkenazi communities. Apparently my paternal ancestors became just such Yiddish-speaking, Slavic food-fancying followers of the Ashkenazi rite … clinging to only one small piece of their Sephardi heritage.

As Jewish marriage is sanctioned by a rabbi in a beit tfila (‘house of prayer’), Jewish divorce must be sanctioned by a rabbi in a beit din (‘house of justice’), a court. Lodged in an old brownstone, the Brooklyn Beit Din to which my wife and I took our crumbled marriage in 1974 was lined from floor to ceiling with massive, leather-bound tomes of law and prayer ritual. A study hall too, it was further lined with heavily-bearded men wrapped in black and white wool and silk prayer shawls, davening—praying with a back-and-forth rocking motion—chanting as much from memory as from the texts in their hands.

While they prayed fervently with attention firmly fixed on God, they were also the court’s official witnesses, missing neither a spiritual nor a judicial beat. When the rabbi heading the court, the Rosh Beit Din, asked if there were any children born of our marriage and we answered in the negative, the seemingly most enraptured of the praying men burst out with a joyous “Danks Gott! No children!” all but blowing me off my feet.

Of all the parts of the divorce ceremony, none seemed more important than precisely determining our names, a result of the centuries of destruction visited on Jewish documents as much as on Jewish bodies. The Rosh Beit Din strove to ascertain every name I had ever gone by at any time or place.

“What is the name on your American birth certificate?”

“Nathaniel Abraham Wander.”

“And what other names are you known by in America?”

“Nat, Nate.”

“What name are you known by in the State of Israel?”

“Natanel Vander.”

“And, what other names are you known by in Israel?”

“Nataniyel, Nati.”

“What name are you called by when you stand before the Aron HaKodesh (‘Holy Ark’) to read from the Sefer Torah (the handwritten scroll comprising the five books of Moses)?”

“Avram Nechemya ben Ephrayim Elisha.”

Now we were down to the bedrock, my Jewish name, my real name as it were. It would gloss in English as ‘Abram Nehemiah son of Ephraim Elisha.’ These patronymics (matronymics in a woman’s case) were passed down through the generations, putatively since the gathering in the desert—B’Midbar, or ‘Numbers’ in English translations. To complicate matters, it was also customary to name children in the local language with names whose initial sounds approximated the Hebrew ones, much as a Chinese girl named Jing might go by Jennifer in an English-speaking place.

My mother apparently thought Nathaniel admirably American (I doubt she even knew it was Hebrew), likely appropriating it from Nathaniel Hawthorn—she was a prodigious reader. Why Avram became Abraham in America, I’ll likely never know, but in the Bible, God changed Avram’s name to Avraham in anticipation of the miraculous birth of his son Isaac when Abraham was already one hundred, his wife Sarah ninety-nine. A ‘60s Israeli pop song declared: “Im Adonai rotzeh, afilu matateh yoreh,” ‘If God wants, even a broom will shoot.’

This Avram/Avraham thing looked to become a pivot upon which the Bet Din could teeter-totter forever. The presiding rabbi ran through the litany of questions regarding all the names I had ever been known by. And again. And again. He would change the order, or the wording, or throw in an unrelated question or two as if trying to catch me off guard when he snapped out the crucial: “What name are you called by when you are called to the reading of Torah?” My answers never varied.

At last, as if almost against his will, he accepted them. “Though you speak Hebrew with a modern Israeli accent,” he said, “I can tell you are Ashkenazi. But Avram is a Sephardi name: Ashkenazim use Avraham.”

The rest of the ritual went off hitch-less.

That evening, I related the experience to my father. I described how the Rosh Beit Din had been obsessed by Avram—which I’d inherited, after all, from his father—insisting it was a traditionally Sephardi name.

“That’s because we are Sephardim,” my father said, proceeding to tell me of his family’s migrations from Portugal to Holland to Germany to Poland, of which he knew only the outline. I was so flabbergasted, I didn’t think to ask why he’d never mentioned it before; it’s too late now.

Yet, almost forty-five years later, it puzzles me still. Would it have been embarrassing to be a Sephardi among Ashkenazim, even after four hundred years of assimilation? Were Sephardim still not accounted real Jews in Ashkenazi Europe? Were they tainted by cultural associations with Arabia and Spain? Or worse, polluted permanently by the (even if forced and faked) Christian conversion of so many? How very sad if Jews had to hide their ‘true’ identity from other Jews.

NATHANIEL WANDER is a Columbia-trained anthropologist. The author retired from Edinburgh University to study woodpeckers in Belize. This essay is from his forthcoming book You Are Here—X: Tales from the Evolution of an Anthropologist. Its sixth published chapter, “Cowboys and Indians,” recently appeared in Jaggery—an online magazine for people of the South Asian diaspora.

NATHANIEL WANDER is a Columbia-trained anthropologist. The author retired from Edinburgh University to study woodpeckers in Belize. This essay is from his forthcoming book You Are Here—X: Tales from the Evolution of an Anthropologist. Its sixth published chapter, “Cowboys and Indians,” recently appeared in Jaggery—an online magazine for people of the South Asian diaspora.

Featured image: An auto-da-fé of the Spanish Inquisition: the burning of heretics in a market place. Wood engraving by H. D. Linton after Bocourt after T. Robert-Fleury. Wellcome Collection.