Beware of the spiritual journey. You may end up in a place that’s not so comforting. I discovered this hard truth at a meditation retreat in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Vipassana Meditation, the time-honored method attributed to the Buddha, gave me vision, startling vision, and terror. It unanchored me.

I’m going about my life pretending it didn’t happen. Nothing happened. I’m engrossed in the daily stuff that takes up a day, absorbed in my semi-heroic existence of the average man, woman, like you, perhaps, and seen at the coffee shop and in the classroom and at a multitude of tasks, enduring, getting by. And I still like people in doses, and rue the frightening news but keep my chin up, every day, and my shoulder to the wheel and . . . stop short at the wall of clichéd, hackneyed language that trips me up, up. Interrupting myself. Breaking down a bit, not too terribly. Because I can’t go that route. I can’t.

It is not about language, oh, no, oh, no. But what can’t be expressed.

“No, I couldn’t, doctor, tell you why… what I saw.” I’m a wide-eyed patient on a black leather stool in an examination room. I’m studying the walls with deep, deep gratitude, actually pleased to be here. And getting up and going about my business, I tell you, fit as a second-hand fiddle picked up at a Mexican flea market. Bow me. I screech “hello” and “how’s it going” and other sounds akin to the regular noises of the marketplace—conversation, I think they call it, small talk. Social intercourse. I engage in it like everybody else.

And grunting. I do some grunting in bed. “Oh, baby, this is all we got.”

And praying. I get on my knees and, well, pray, as unfashionable as it is. Adopt the time-honored posture for appeal to the divine presence in the universe that appears so, so…

I’m blank. I’m on the cusp of revelations the world may profit from. I’m not mad. I’m a fan of demented seers is all. That gang. Mr. Poe, Eureka, cometh to mind. But that’s just… literature. Words. More words. I’m wordless. I’m not. I’m sitting here writing you, sensibly, with my mind clear of the thing I saw.

I’m wrecked. But there’s no sense dwelling on it. There’s so much to swear by. I’m living in extraordinary times on the dying planet that still offers bargains in natural beauty only a few miles away, an ocean and waves, and mountains and trees, and even beautiful manmade sights like bridges that span waters and magnificent buildings and crowded sidewalks with people of all kinds moving in one, solid direction according to the laws of foot traffic. Only a few go the other way, grim faces they are. And I’m despondent when I glance up at the pleasant, afternoon sky and see behind it, behind it. Daytime turns to night and… terror upends my life.

I saw it all. I stand outside myself and love me, me.

Stephen believes in God but doesn’t know how to handle it. Stephen is a major disbeliever with a hankering for the absolute. Stephen believes in many things but indifferent he’s not. Stephen saw the universe so scarily one night he might have gone mad forever.

He didn’t go mad forever. He is not cracked. He is whole.

Wholly me. Holy me. Holy all. All, all are in it together on this ridiculous planet with its churches and synagogues and temples and mosques and ashrams and improvised basements. I get perturbed in apocalyptic times because it all seems so senseless, this rush to kill ourselves, when we’re not that important. Oh, aren’t we? No, we’re not. Glorious beings that we are… Inversely, our insignificance should goad us to accommodation, not tragic hubris. I despair. But I inject myself with hope, with hope. And gift—gift is the new verb—whenever I can.

I do my best for you, reader, who might be distressed beyond your endurance—oh, so much shit happening around us—beyond your ability to hold it together. You might be hungry, hungry for consolation from the heavenly quarters. Or anywhere down here, you know, the spiritual route, the secular way. And perchance you are embarking upon a course of meditation in the fragrant valley near your home, or on a lone mountaintop, or in the vastness of the desert, like the Christ himself, or on the ocean shore. Or you just might be practicing an artful form of closed-eye seeking so diligently in your cozy den that a suburb might be the site of your own dissolution. Step outside and, and… If you don’t watch out, God might enter your life, not exit it. And that is an unspeakable load to bear.

Ave Maria sing the Catholics. Out of visions in the sky and triumphant unveilings of nothing, nothing come prayer and low chanting, and a mother’s breast to suckle.

I am a diehard Catholic. I am lonely down here, Maria.

* * *

Ave Maria. I signed up for a 10-day meditation retreat in the Sierra Nevada foothills in California. I had been spending twenty minutes a day in cross-legged devotions at home, sometimes twice a day, and learned of Vipassana meditation from a friend who practiced it and recommended I try it. I battled busyness in my head at the outset, no good at it, discouraged. I had no one to help me out, all of us at the retreat bound by the rules of Noble Silence, no communication of any sort allowed—no signaling, no small gestures, no talking or whispering or nudging or making eye-contact with anybody. Excepting God. You could carry on a conversation with him if you found her in the neighborhood. The neighborhood was the woods outside your cabin door. Small paths led to wider roads of the mind in a meditation grove where people sat on rocks, and walked, and leaned down and touched flowers and cried.

“Hello, Mr. Flower,” I said. “You are so beautiful. I’ve never seen you before.”

Mr. Flower bowed his yellow head. I kissed him, on the top of his head.

It was all due to the third eye. Meditation opened it, constant meditation in a dark hall. We were instructed in the strict form of Vipassana, step by step. It was intensive, with proper breaths a big part of it. Around the seventh day, I opened up. If it wasn’t my third eye that blinked awake and saw the world clearly for the first time, it was another faculty unknown to me, another organ in me. I don’t care what you call it, what I call it. I don’t care if you deride it. I know it was holy and good, Godly, the saint’s way, and absolute. It was so peaceful, loving and generous a feeling I count it a taste of heaven. Lizards looked at me from atop rocks and understood too. I sopped it up, the remarkable expansiveness emanating from my heart. Then the third eye enlarged uglily.

I’m shut down now. I’m operating with my regular senses. I’m far from that state of rapture. Years ago, it happened. And never swept me up again. I write in a normal state of mind. I use words from this side of the experience, not the other. The core of it. But that would probably be futile, anyway.

“Like wow, man. There’s not a lot I can say. It shattered me. It broke me. I picked myself up.”

I am past worrying about anything bad happening to me.

“I sit down. I write essays. I grade papers.” I enjoy the night sky with its stars and bright moon and occasional jet nearing San Francisco International Airport or the smaller one in Oakland. I appreciate the finitude of the view, as if it all takes place before a black curtain. I go inside. I steep a cup of hot herbal tea. I put my feet up on a footrest in my study and flip open a book, a poetry book, a history book, a novel, a biography, a memoir, a mystic’s writings, any book, really, with weight and substance, if not some light, goofy thing, and rejoice.

Holy holy holy. I relish the assurance of four walls, a ceiling, and two windows looking out at that same benign night sky.

Night sky. Night sky. Ave Maria.

“But I’m okay, basically. I ran into some trouble under the stars.”

I’m well liked in the ward on account of my affability and imperturbability. I play cards with friends with bands around their wrists, and smile often. “I saw it all, all.” I whisper for hours on end in my corner and nobody gets mad at me or kicks me out into the hard, cold winter night under the stars, which hide it all, all. They are only trinkets in the sky to confuse us. They convince us of order, of grandly conceived order. We are only a small part of it all, all, we tell ourselves, standing on firm ground. Terra firma. But they’re decoys. They cover up for God, the face of him, and obfuscate. They blur the view from below, and mar the picture we crave and fear to see, the endless picture without a frame that will change us, like exposure to something upsetting at a museum, a grotesque painting bathed in truth. They twinkle and blind us, do these stars, these tidy remnants of a Copernican world, which we still live in. We can’t escape it. There’s a conspiracy to propagate it. The Bible is still the bestselling book in the world, and the movies say the same thing. The universe is wonderfully, splendidly varied and big, and closed. I learned otherwise.

“The stars are just the picket fence in the cosmic neighborhood. I crashed through it and can’t find my way home. Meds at six o’clock. Bed at nine.”

Ave Maria. I am not confined in “a safe, secure environment,” like my friend the schizophrenic poet Salinas who witnessed the devil taking a piss in the men’s room, and didn’t like talking about the stars much. “I cut that line out of my poem. Fucking stars. I like it when it’s dark and you can’t see nothing up there. That’s my life.”

“At least you got the grass down here.”

“And tamales.” He rolled a purblind eye at me.

Poets and stars. I’m comfortably at home. I’m entertaining literary matters, of all the stupid ways to waste your life. But I’m me! I’m free! I’m beholden to the vision for courage. I acknowledge a beneficial aspect to it. But I mess up. I suspect a damning violation of literary etiquette has been noted. How dare I use the imagination in a piece of nonfiction? goes my concern, a recurring one. Has the essay been destroyed, its credibility shot, or been labeled a laughably loose ethnic try by the zealots, those critical types who track down punks like me? Who break down walls. Who carry buried fears that might motivate the whole damn thing. Fears of, of… The new Star of David is brown and in the shape of a taco.

Nonsense. Buck up, old man. Get back to stars and God. Fight or flight? Both. Face the accusation.

“Non-nonfiction.” No, it is not, it is not. It is a real account of something that really happened to me. It is all real, all truthful. I make a pit stop in the state ward for the non-criminally, non-fictionally disturbed because it is only right and proper to do so.

“I saw it all, all.” Slap me.

The ancient Vipassana way of Buddhist meditation was responsible. Supposedly, it can be traced to Gautama Buddha and his proven method for emptying the mind of gunk and accessing the pure, still center where love and compassion abide. Whatever it does in the religious line to make you a better person, it also upsets your balance on the earth by allowing you to see past the show around you, like an LSD trip, a good one, and appreciate the view, the freshness, the vividness of the drab world come to life. It can also work like a bad LSD trip, a bummer ride, and tear things down, terribly, terribly until there’s nothing left of the ground to stand on.

So it went badly that night for Stephen.

“How badly?”

“Horribly.” All because he looked up while drunk on the secret Vipassana concoction, perfected by the Buddha himself more than two millennia ago, according to the guru in charge of the worldwide Vipassana ministry. This man was named Goenka, and nightly he gave videotaped lectures in a series prepared for the program. Formal introduction to Vipassana entailed theory and practice. Dutifully, Stephen attended the viewings in the darkened meditation hall with the rest of the retreatants. Squirming on a plump cushion, he looked up at the screen and listened intently as the master charted the universe inside you. It was all right. He was good.

He boiled it down. What every retreatant was after. Peace. The end of suffering. Wanting. Desiring. Agonizing over existence instead of passing through the world beautifully, gracefully, lovingly, without uncoiled emotions, feelings and thoughts bringing disharmony to oneself and others. To the world in one’s orbit.

To get there, you must meditate. The Vipassana method consisted of an upright posture on the floor, hands folded in your lap or cupped on your knees, and back as straight as possible, buttocks supported on a pad of some kind. However, if that didn’t work, any reasonable attitude of concentration was acceptable. Eyes stayed closed. Then came soft breaths and hard breaths and stillness practiced for long, uninterrupted blocks of time. It brought about a change in him, gradually. Stephen began to break open. One day, he walked on air. He trod a few feet above the ground on the hiking trail at the retreat center. He began to laugh inside at the absurdity of it all, the beauty, the goodness, the immeasurable wholeness of things. Everything worked together constantly, constantly. He lowered his foot on the dusty trail as his other foot rose behind him in one fluid motion, a constant stepping into air and out of it, and thus he glided on the nature trail with a beaming smile on his face.

When he looked up at night it disappeared, the daylong smile on his face. It evaporated in the anguish of what he saw. “Oh, man. This is bad, bad.”

He kept walking, fast, back to his cabin as soon as he glimpsed it, the truth, the awful, unforgettable truth. Then he snuck another peek up, and that’s why it stuck so horribly in him. It came alive, even more. The living, monstrous universe. He doesn’t remember what he did next. Hang his head down? Look away to the bushes by the fence, the wide palings that marked the path? He can’t reconstruct the encounter to that extent. But he did scream in his head later that night. He had such a terrifying vision of the way things are he feared his sanity might actually be at stake. He put himself to bed. He lay under the covers and trembled.

“We’re not held up by anything. It’s unsupported, everything. That’s an illusion, our fixity. Just a show we’re forced to believe by the books we read and the movies we watch and the lives we lead. But nothing, nothing about it is stable. Nothing about it is. Oh, if we only knew! It couldn’t be borne, couldn’t be borne. We’re nowhere. And it’s big, big, this nowhere. It never ends. But there’s no accounting what this ‘is’ is. We’re in the middle of ‘is’ because there isn’t ‘is not’ but nothing is something and, and… Oh, my God, oh. It’s what is because something has to be. Only nothing can’t be. I, I saw it all, all. I swear I did.”

That’s when he screamed in his skull. It was a loud, shrill yell, an agonizing clutch at his head such as Munch caught, without the gesture. Just the silent noise. “I’m trapped on this fucking planet. Get me out of here. Please. Out of here. Nowhere to go.”

He came to a conclusion on his side in bed, clutching a blanket to his chin. “The nut wards are home to people who have seen it. I’m sure of it. They limp in after visions, and stay. Or tramp the streets endlessly, babbling away. They can’t take it, either. They’ve seen it too. At least a few of them—somewhere, they roam, the unlucky ones who have seen it all, all. Our father who art in heaven. Hallowed be thy fame. Thy blubber lips. Blub. Blub. Blub. Thy blueprint done. Thy rootless son. Thou scary one. On earth as it is in… nowhere else at all. Preserve us our fantasy the day after tomorrow and every day after. Amen.”

Ave Maria. I was given a direct line of vision to, to … the end of it all, the beginning. Wherever it was, I don’t want to be there again. I dare anybody who’s been there to go back, and revisit it, and come back and live with it every day. Carry that picture in your mind, and deeper than your facile mind bear it afresh in your treasury of vital knowledge, your survival kit that determines life and death for you—your brain zone marked CRUCIAL DATA—and be normal. No, it can’t be done. I approached it only through meditation, by accident, basically, and forfeited it, as soon as I could. I dumped it, which was easy. It’s too profound a vision to maintain, too unsettling a fragile instance of reality to preserve.

Brute reality. I have ceased to see it. Only a few, a few I say learn it. Not in school, but in the woods, on drugs, after meditation, sex for the record books, a visitation from God in sleep or a crew of extraterrestrial beings infusing the mind. After loopy preparation. Not from bestsellers explaining it all. Not from studies printed in eminent journals. No, not even the shrewdest scientists convey the necessary information to reconstruct it adequately for a short, imagined visit. They don’t provide greater guideposts to entry.

I need to establish my credentials. I own a P.H.D. (Plainly High Development) in Cosmological Matters. I exceed the masters in the field of Big, Big Stuff, the Nobelists with squinty eyes and long, flowing locks in their European towers and American universities and Asian laboratories. Oh, all these geniuses! I am one of them. I am a scientific prodigy without a formula, only experience. I can’t even read the literary gems in the broadening genre, quality essays about the cosmos or the brain or the maligned butthole without impatience creeping in. The details snag me and disturb my absorption, inevitably. I can respect them but not love them.

I don’t tackle bona fide science writing, either. In my opinion, none of it can make the astronomical ideas real enough to change what you see around you, every day, as you go about living. It can’t illuminate the mind sufficiently. The unreal nature of our understanding of the universe remains intact no matter how lucid the explanation of what’s really going on up there, all around us, elementally. Respectfully, then, I don’t credit the experts with any profounder knowledge of it. I don’t believe that these good men and women in lab coats and dusty classrooms and behind massive telescopes see it any better than any of us on a daily basis. They’d be crippled for life. They’re rescued by the distancing calculations of their extraordinary minds, which are as average as any layperson’s in taking it all in and understanding it and accepting it for what it is.

“My God, Ann, I can’t go home to supper tonight. Ever. I want off this planet, please.” The scientist bent over the lens finally got a glimpse of it, after observing it for forty years.

“I told you not to take up yoga, Ben. Let’s call it a night and get you to the clinic. You’re green.”

I’m pale. I’m attending myself with a defiant act of writing. Could be good. Could be bad. Could be all he had left before he went mad. It’s too much, too impossible, and hell on a career, on a life, grasping what is going on up there. I get it. I’m scared. Who wouldn’t be? Under it? Gazing up and seeing it?

Ave, ave, ave Maria. At the conclusion of Goenka’s lecture, the last activity on the day’s long agenda—meditation and more meditation made up most of it—I flowed through the heavy doors of the main hall with the rest of the men, the men and women separated for the duration of the retreat, the obvious genders, anyway, and put my dusty clogs on outside. I joined the general shuffle under the stars towards the cabins and tents, and in silence navigated a dark pathway with a bunch of scruffy nature bums in their twenties and thirties and in their rightly calibrated minds—peaceful, radiant souls in earnest retreat they were, and following some law of station we massed behind an old Korean-American guy in his hale eighties, I later learned, on a knobby walking stick. We had come ready for the woods in mid Spring, and received the night air in jeans and down jackets and cargo pants and parkas, silent, silent, all of us, moving along. We lit the path ahead with our flashlights, zigzagging the beam discreetly, or concentrating it on the ground below. I scanned the sky for beauty, for comforting figures of order and permanence. I fell into a deep, black well or shaft or timeless tunnel and lay at the bottom of it, looking up, and nothing in edgeless space performed its usual function of stable signpost. Only the dark immensity existed familiarly.

There wasn’t much to see separately but all of it could be accessed with its constituent parts subsumed and fuzzy, as if struggling to be seen under a hazy film covering the gigantic, black spread. Stars shone feebly. The moon maintained quaintness. Perhaps a meteorite trailed a weak tail. Then it split open. It brought me nearer. There it ostensibly stood as my friend the celestial raiment, only brighter, more vivid, and fake, with a meretricious quality, existing as a made up thing. And there I paused, aghast, craning my head to identify the eternal patterns buried in my skull from first glance in the tribal desert, millennia ago, and astounded at the selfsame deceptive easiness of the largely incoherent sham. Starstruck I am, without a star to fix on, and abruptly losing my footing, slipping a bit, my knees buckling.

I ducked my head down. I couldn’t bring it up.

“But I have to. Oh, my God, no.” I averted my eyes for the last steps to my cabin.

I slumped against the door and breathed hard.

“I only have two more days of meditation. I can do it. I can make it. I didn’t know. I didn’t know. I got to hold on. Oh, get inside. Get inside.” In the safety of my single-occupancy room, my monk’s quarters for the week, I sat on the edge of my neatly made bed, with hands clasped between knees, and stared blankly. I appreciated the floor under me, and the walls around me, and the door to the hall with a knob sticking out, and the dresser in chunky relief. I loved the solidity of my surroundings, my immediate surroundings. I could reach out and touch things if I wanted. I didn’t move for a long time, aware of how good I had it, where I was.

“Where we are is, is…nowhere known to us. I see people running down the street screaming. Forget Ginsberg’s starving hysterical naked minds of a battered generation. They got it easy, knowing nothing. I know nothing. I saw everything, at least a part of it. I stood under it. I, I… got to quit talking to myself. But it helps. Do we only have ourselves in our lonely corner of the universe?“ I got under the covers. I soothed myself to sleep. I mumbled prayers. I masturbated. Did I? Could I? Was desire possible anymore? Fantasy? Was that the only out? I knew staying in it was bad. It wasn’t possible to live in the place I’d been. Oh, no. That couldn’t be, ever. I slept it away, the walls fading before my eyes.

Around four a.m. a monk made the rounds of the Vipassana haven in the sacred hills of California, clanging a bell. I got out of bed and went down the hall to the bathroom and did my thing, using the toilet and brushing my teeth and slapping my face mildly at the end of the long counter with many sinks, at the screened window, getting a dose of cold air to wake myself more fully. I hadn’t had my coffee yet. Was life on earth sad, or what? I shaved. I hate shaving. I am bad at it. I swiped at the soap and stretched my chin out and shaved against the grain, the only way for me to get a clean shave. I tapped the razor blade against the sink to see the water drops fly. I was still high. My mind hadn’t closed up. I inspected my chin. I pronounced it a decent job under the dim lights that conserved energy and cast the bathroom in a sickly yellow. But I didn’t mind. I couldn’t argue with environmental resourcefulness. I couldn’t argue with anything, really.

“It’s going to be a good day,” I told myself. “Two more to go.”

I stepped outside with my toiletry kit in hand, imbibing the fresh air and eyeing the woodsy view with a brisk face and a bare chest. Ah, nature. You are my friend in times of distress and confusion. Wonderfully, it appeared normal. 3D depth provided clarity. Like, it was okay to be alive on this morning and enjoy it. Everything notched into place.

Operation Natural Deception resumed. Birds chirped. The stars faded fast in the cobalt blue sky, and the outlines of the trees rose enormously around me. The plentiful squirrels stood on hind legs in different corners. It was like a marvelous set we lived on, the script-in-progress written by God, forming our words for us before we even opened our mouths. Fated, fated, controlled are we, playing our roles on a determined stage.

What, am I crazy? No, I’m not. I’m just needy and prone to comforting fictions when I’m scared or have been outwitted by, by… Vipassana meditation.

“It’s time to go home. Roll out of here in a day.” I had to get back to work, if I could manage. Stay serious. Playful. Intent. Turn on the computer and essay a trifle on kissing a flower that trembled stiffly on a lone stalk, a yellow beauty, or rhapsodize on a line of ants marching in the dirt. Bent over the thin trail of quivering black insect life, I had extolled the graciousness of the universe that allowed me to witness this mighty procession, this necessary embodiment of ever-moving life on earth. “It could be no other way now,” I had mumbled to myself. It was all building up to this, what I had noticed before the lockstep campaign passed under my nose, the few ants milling about my door.

“Wow.” So much had been given to me! I could handle this material with abrupt sentences that ended with periods, or even long sinuous ones, as long as each contained an appropriate end sign. Period! I didn’t ask for much. I could record commonplaces, and mutter, “holy, holy, holy,” upon completion. Or I could do nothing, nothing at all and not worry that my part in the scheme of things had broken down. I had lost faith in it all the night before and would never look at it the same, at least for a long, long time. Right under it again, in future, I wouldn’t embellish the firmament in the soft human light of divine placement and cross-borne favoritism, as we view it, here in the West. Like it or not. That’s us. I couldn’t play the game anymore, the fun dioramic fantasy taught me in catechism and reinforced in Mass weekly, not after the sweep of my spiritual excursion that previewed love and terror and fear on a scale I never imagined. I measured the waning night, by the cabin door, maintaining my fragile peace of mind till the inevitable slide into normalcy erased the last vestiges of the startling vision and encouraged a romantic repurposing of myself the next night. Oh, yes, there I would stand in my yard in the suburban Bay Area, surely, basking in my sly centrality below the anemic stars and filmy clouds and pockmarked moon, all of it tucked into the Godly dome called The Sky Above. But I knew better than to trust it.

Saint Thomas Aquinas had such a powerful, unexpected sighting of God or ultimate, sacred reality or, for the irreligious reader, the adamant atheist and Godless one, the whole picture that he cast his eyes down in humility—such a flooring encounter with the unveiled universe occurred during Mass that he couldn’t persist in his trivial life. He refused to finish his magnum opus, the Summa Theologiae, based on what he saw. He famously said: “I cannot, because all that I have written seems like straw to me.” Did he know all there was to know? All that is humanly possible to comprehend in a flash? A sustained moment? Did he leap past the terror of the physical universe that dwarfs human understanding and mocks sanity, and land safely on the right side of totality? Did he acquire a reverent state of mindless mind, and feel free, without fright, without need, without any human bother, only awe? He saw it all, maybe more than me, certainly more than me. I only saw a slice and chickened out under it, cowering like a child encountering its first scary Halloween mask worn by a mischievous father. I lie. I saw it all, all.

STEPHEN D. GUTIERREZ is the author of three books, most recently The Mexican Man in His Backyard, and an American Book Award winner. His nonfiction has appeared in Fourth Genre, River Teeth, ZYZZYVA, and other magazines. An essay in Waccamaw 16 received a Notable Essay citation in Best American Essays.

STEPHEN D. GUTIERREZ is the author of three books, most recently The Mexican Man in His Backyard, and an American Book Award winner. His nonfiction has appeared in Fourth Genre, River Teeth, ZYZZYVA, and other magazines. An essay in Waccamaw 16 received a Notable Essay citation in Best American Essays.

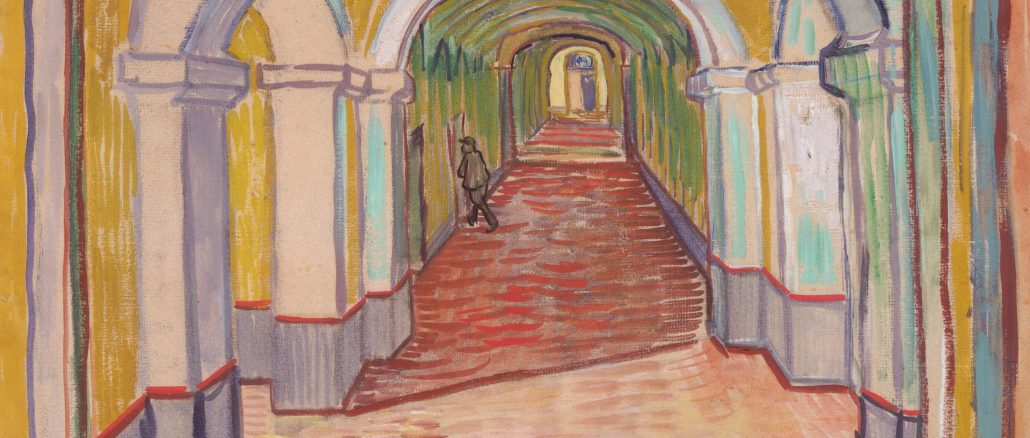

Featured image: Vincent van Gogh, “Corridor in the Asylum,” oil color and essence over black chalk on pink laid (“Ingres”) paper, September 1889, bequest of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1948, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.