Mark Harris’s art judges what is wrong without judging humanity. He immortalizes the pain he sees inflicted on black men in American society without a hint of othering. He somehow manages to include himself inside the discussion, even though he is one of the often othered at whom society hurls unfair, often unjust and horrific jabs, even reaching into the hatred well at times.

What I admire most about San Francisco-based visual artist Mark Harris is that he lacks a chip—the kind that rests heavily on the shoulders of so many in the marginalized communities of our polarized nation. Mark is capable of inclusion, and thus, he creates conversations that unburden through education and enlightenment.

Spending time with Mark tends to bring one to the precipice if you look into his work—if you choose to have the pluck to pause. He has the ability to access a viewer’s subconscious through his imagery, within which he creates a narrative that demands attention. There is a future that he is brave enough to envision and one he asks his viewers to consider at length, and then in hope, embrace.

Shedding our rain-dappled gear at his studio’s door, I stepped down a few colorful steps into Mark’s work area, walls bathed in natural light exuding his activism, pieces in varying degrees of completion leaning into one another around his lively work table. Mark was generous in his response to my uncomfortable attempt to check my white privilege as I took in his body of work. He opened a portfolio and pointed to the work that transformed him from a suit-wearing corporate wage-earner to activist artist. The piece, like much of Mark’s work, was exquisite—and heartbreaking.

Andrea Lynn: Tell me about this piece that embodies your shift into the role of activist artist.

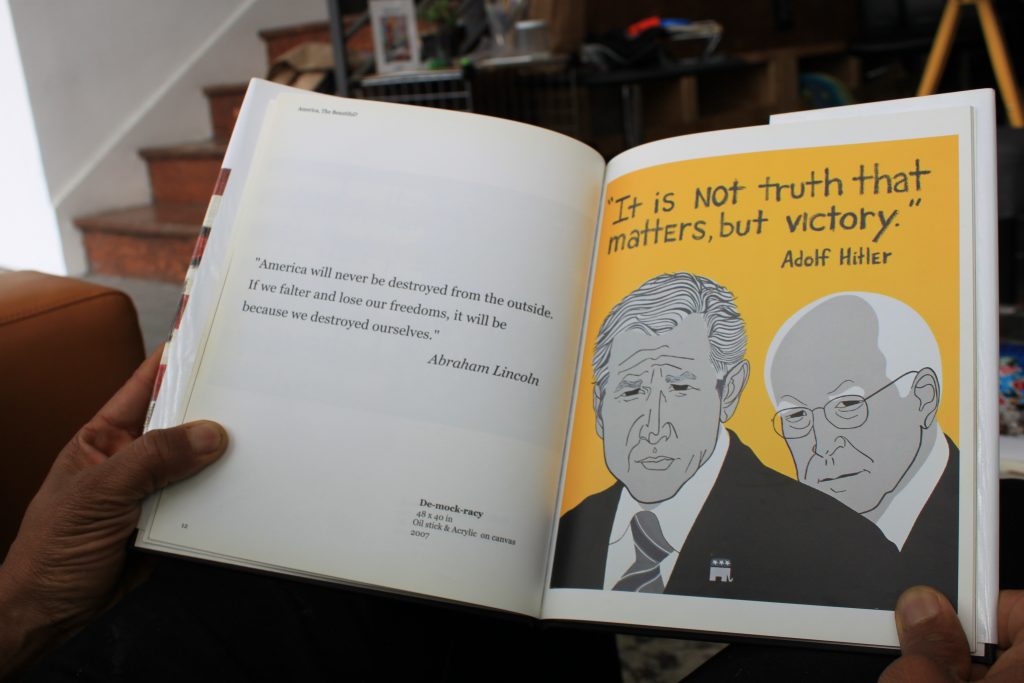

Mark Harris: It was 2007. I was in a creative transition with my art practice. I was working in South San Francisco for a biotech start-up. I’d finished reading John Dean’s book, Worse Than Watergate. I was upset and angered. I began to wonder, what recourse do any of us really have? I wanted to, needed to respond.

AL: So, you just started painting?

MH: I wanted to present an alternative narrative to this whole propaganda campaign going on at the highest levels in our government about the invasion of Iraq. I was in the moment; it wasn’t really so much a conscious decision as a response based on what I was feeling. I didn’t think I could sell the piece. It wasn’t about that, but I needed to respond. The entire series, it just evolved, one painting at a time.

AL: Did you consider exhibiting this body of work?

MH: I did! My first exhibition of work from this series was at Linn-Benton Community College. There was a national, juried exhibition called “The Political Show.” They accepted all three of the pieces I submitted. I also exhibited some of the same work later that year during SF Open Studios. I remember a guy came up and actually spent some time with the piece “De-mock-racy” and asked questions. We had a great conversation.

AL: So that had to feel like confirmation of your work. Did you really dive into political art at that point?

MH: Well, no. The 2008 election happened, and I felt good, great! I went back to abstract expressionism and found I could make money at it.

San Francisco

AL: Were you also responding to something larger, or something else beyond the administration in power at that moment in America?

MH: I looked around San Francisco and was wondering what had happened. I thought, and think, that this community needs to be engaged in the conversation—in the here and now. Fifty years ago, it may have been about society at large. Now, it seems to be all about technology—sort of a new Gold Rush.

AL: You were responding to San Francisco’s transformation?

MH: I felt like San Francisco wasn’t paying attention. All the changes to the city felt like a personal afront to me. There’s really something about the ethos of San Francisco that does allow you to evolve who you are. People still feel like they’re going to come here and be transformed. This transformation in me never would have happened if I weren’t here. With the proliferation of connectivity and communication I decided ignorance could not be an excuse anymore.

AL: You left the corporate world and dedicated yourself to your practice—to an artist’s life?

MH: This is where artists have to come in—we are the visionaries who can create what the future can look like as the old systems die and are reinvented; this is our mantle.

AL: That’s a heavy mantle. How do you think artists can accomplish this form of leadership?

MH: We get people’s attention, make them question what they’re seeing. We bring people to a place where they want to do something about it—whatever they in their own ways can do.

AL: You talk about what’s happening, and I know there’s a lot behind that, but can you articulate the happenings beyond the political propaganda around which you want to create responses?

MH: I want to wake people up—there’s so much we need to be paying attention to; so much inequality, and so many struggles. I want my art to be a glitch in the system; we’re indoctrinated into the status quo—we’re just used to society moving along.

I had been taking in the arts here—getting to know the artist community. I felt that the artists who are here have a responsibility—I feel that I have a responsibility. I didn’t think I could sell any of my political work, but it wasn’t about that. It was about having a way to respond and to bring that deep engagement back into the community.

Return to Activism/Ferguson

AL: What caused your move back into political art, activism art?

MH: Ferguson. It was just the straw that broke the camel’s back for me. The things I took for granted were shattered. Things I was sure about were gone. Yes, I had grown up in the Deep South, in Atlanta. But I was a post-civil rights baby. Things were different by then. My parents, all the adults, they told us how to behave; my parents had grown up in North Carolina, but their stories of oppression sounded like ghost stories to me when I was young. You know, kind of like, well—it’s behind us. That was all ancient history. The events that transpired in Ferguson [in reference to the fatal shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown, an African American, by white police officer Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri] shook me out of my slumber—out of my revisionist history sort of thing.

AL: What did you do?

MH: I began a collage, “Original Gangsters.” It was one of the very first collages I did post-Ferguson; I obviously had a very strong response to that event, that historical event. It’s what really gave birth to this body of work I’ve been doing ever since. In this piece I wanted to create, to give a counter-narrative to what unfolded.

It seems the victims in these shootings are always portrayed as the criminals—they are portrayed as these grown men who are wild… They’re not painted as the kids that they really are. Law enforcement’s response is, they fear for their lives. So, I wanted to create a counter-narrative to that. I came up with the title because as I was creating this piece, I saw the police as being gangs; organized, with an agenda. And that, these are young men who are being killed. There’s a term in West Coast Hip Hop culture called O.G.—Original Gangster. Well, I felt like we didn’t have gangs in our community when we were first brought to America. If you look back at the history of African Americans in this country, there were no gangs in the earliest days of our existence here. We lived very collectively, we took care of one another, we looked out for one another, and I believe the gangs in our communities are by design—but—that’s a different conversation.

AL: You said Ferguson, and the police killings, felt more personal to you?

MH: Yes. In the arc of time, again, to be reminded that your life doesn’t really matter.

AL: Are you referring to the lives of African American men?

MH: I’ve been acculturated to this society; being told as an African American man that you can’t be too angry, but with the brutality that occurred in Ferguson, I decided that was it—I didn’t care. I was going to give voice to him [Michael Brown] and all the others. The work, my work, is confrontational, but that is not my MO as a person. I am approachable. I need to be able to create this kind of work and then be capable of holding a conversation about it—that’s my obligation.

Impact

AL: In this moment, what do you hope happens when somebody spends time with an image like this?

MH: I hope it impacts them in a way that makes them want to make this piece of art truly a relic of the past. I hope it would inspire them to want to see wholesale change initiated, started; conversations really being had about this issue, because it’s not new. That’s the big separation with this issue for people. For black people and for people of color, this is nothing new, but, for a lot of white people, they don’t know about these photos, or this portion of our history so it doesn’t resonate with them in the way it resonates with me when I see it continuing to happen in the twenty-first century and people want to act like it’s just a one-off; that these young men were so scary that they deserved to be shot in the back, shot while handcuffed, stalked because of what they were wearing. I hope it makes you uncomfortable, deeply uncomfortable—as I feel when I see police lights in my rearview mirror if I’m driving. That’s a reality for me.

AL: How do you reconcile the message in your work with selling it, earning a living from the work?

MH: When I sell a piece like this that carries such a message… I don’t know how I feel about that. Most of the people who buy my work are white. I feel that I need to be a relevant artist, so people spend time with the message. All of my artist heroes, they really put themselves into their work—Pablo, Frida, Miles Davis, Bob Marley—into the message. That’s what I try to do.

Introduction to Art-Making

AL: Did you ever consider art as a child? What was the first work of art you remember creating?

MH: I was seven years old and I loved horses. I asked my dad to draw a picture of a horse. It was a Saturday afternoon and he was watching college football—he probably didn’t want me to ask him about drawing right then, but, he goes ahead, and he takes a minute and scribbles one out. I looked at it and told him I didn’t think it looked like a horse! He told me to go get the encyclopedia. Looking back, it was a great beginning to my creative practice. I looked up a picture of a horse and drew from it. I began to look at things and draw them—sports figures, comic book figures. That’s how I got into a creative practice.

AL: How did you begin your journey as an artist?

MH: It was 2001 and I was soul-searching. I was working in Palo Alto for a multinational company, not in any way thinking of myself as an artist. Around the same time a co-worker had commissioned me to paint something for her new apartment—I painted casually then—a few canvases to decorate my apartment. My co-worker brought some pillows to work that she had used in her decorating as a color reference. She gave me complete freedom to create what I wanted. After a few weeks I finished the piece and she was thrilled with the results. Several months later the economy imploded, and I was faced with the choice of taking a $20K pay cut or being laid off. I opted for the lay-off.

AL: So, what did you do?

MH: I went out and bought all the canvases I could fit into my car; I think I bought the store out that day. I turned the second bedroom in my apartment into a studio and I just started painting, and then painting more, then every day. Every day. I spent a lot of time studying the work of van Gogh, Stuart Davis, Matisse, and Picasso—I was taken with expressionism, abstraction, and cubism.

Art and At-Risk Youth

AL: You work with at-risk youth. What role does art have for these children?

MH: As a child, my interest in art was so beneficial to me. Art can help kids deal with whatever’s going on at home; it’s a way to sort how they feel. My home life circumstances made me very sensitive to people and to their moods. I struggled with my identity—I tried to find myself in sports or in whatever my friends were doing. My friends thought it was cool that I could draw.

AL: Drawing helped you discover self?

MH: Creating instills confidence because a kid can see his creation. It is what you can get back out of art—it didn’t have to be about me but was about the work. I like to teach kids about process; I don’t think enough people recognize how much art is about critical thinking. Kids learn so much as they move through the process, and they build their confidence as they recognize that they are creating. I ask three things of the kids: that our time together be a judgment-free zone, that we respect one another, and that we have fun!

Purpose/Pride and Prejudice

AL: You said you never really thought of yourself as an artist, but drawing was an important part of your childhood. What gave you as an individual the confidence to make the commitment to a life of activist art?

MH: Interestingly, there was something in my church upbringing that always stuck with me: What’s your purpose? We were always told to find our purpose. It made letting go of the pole so much easier—I always knew there had to be something more.

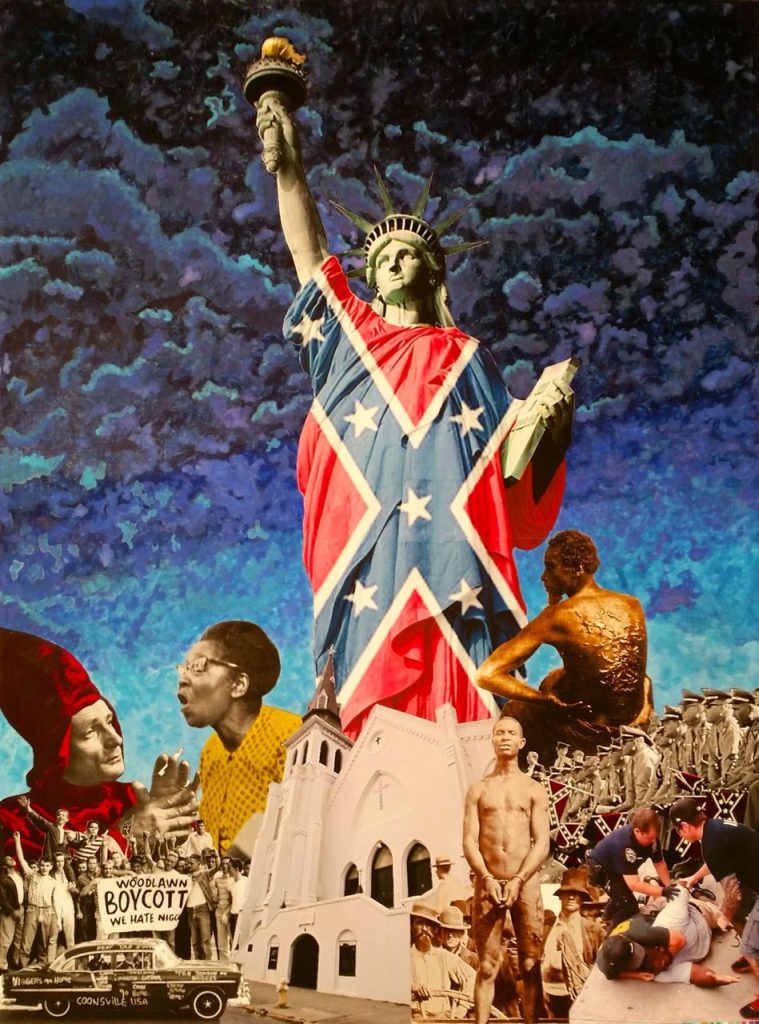

AL: Speaking of church, you said your piece, “Pride and Prejudice,” which was selected for the cover of the San Francisco inter-arts journal Mission At Tenth, was your response to the tragic mass shooting at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

MH: Yes. The story rocked me to the core. This was my response; it was deep. Real. Raw. I knew those people—without seeing their pictures, I knew them. They were just like those I attended church with as a child; I could see their faces.

New Work

AL: We’re looking now at your newest piece. You call this piece, “Man to Man.” How did you come to this theme?

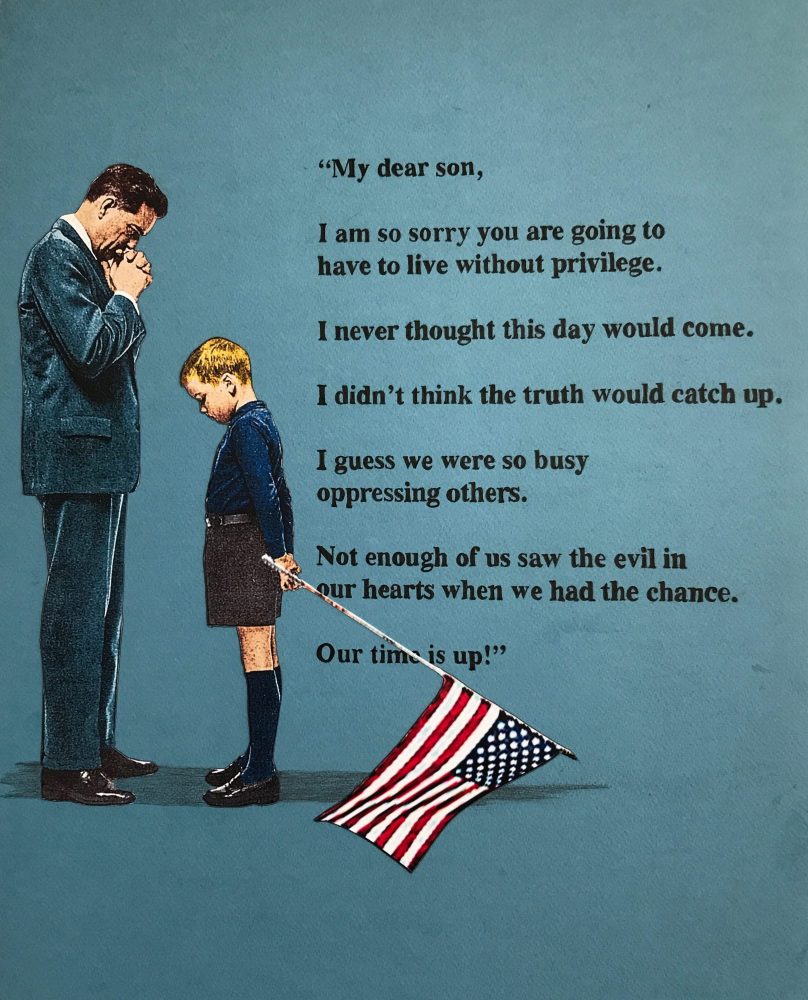

MH: It was the image initially, it was in an ad [circa October 13, 1961] to help raise money for the building of the American Freedom Center in Valley Forge … the letter in the ad was talking about the rise of communism. The father was apologizing to his son, because communism was on the rise and was a threat to their way of life, to the American way of life… I felt like, with what is going on now—the resurgence of isolationism … these ads were essentially propaganda, to create fear of the other, or to believe in this idea of the American dream or what the perfect life is.

I want to use my ability as a visual artist to plant a seed in peoples’ minds because I think the visual artist has access to the subconscious mind. And, we’re also the visionaries of the future so if we can create imagery of the way we want the future to unfold; this is our time. This is something I want to see—I want to see an end to white male patriarchy … the people who created that want to keep the system alive … they know it’s near the end. Time is up!

3.9 Collective

Mark is a member of the 3.9 Art Collective based in San Francisco. The 3.9, as it is casually referenced, is an association of San Francisco-based African American artists, curators, and art writers. Founded by Nancy Cato, Rodney Ewing, Sirron Norris, William Rhodes, and Ron Moultrie Saunders just before the 2010 census, the group came together to draw attention to the city’s dwindling black population. The 3.9 took its name from a report published in the weekly newspaper, The San Francisco Bay View. The paper predicted that the black population in the city would soon decrease to a level equaling only 3.9 percent of the total population.

AL: What is it like to be part of a collective of artists? Do you come to influence one another in your work?

MH: For me, the 3.9 are those special people in my life I don’t need to explain myself to. They are my, ‘I get it!’ community. We don’t need to have a conversation about what it feels like to be black, or to be an artist in San Francisco. When we are together, we are often taking time to simply enjoy being in a group of people with whom we have so much in common. It’s healing.

Process

AL: Do you mind sharing the technical aspects of your mixed media work?

MH: I often worked on canvas and paper with oil stick and acrylic paint pens in the past, but now I am working more on panel because I can go larger scale. I use archival paper for textural effect, and I do a lot of old-school cropping techniques—hand-trimming with an Exacto.

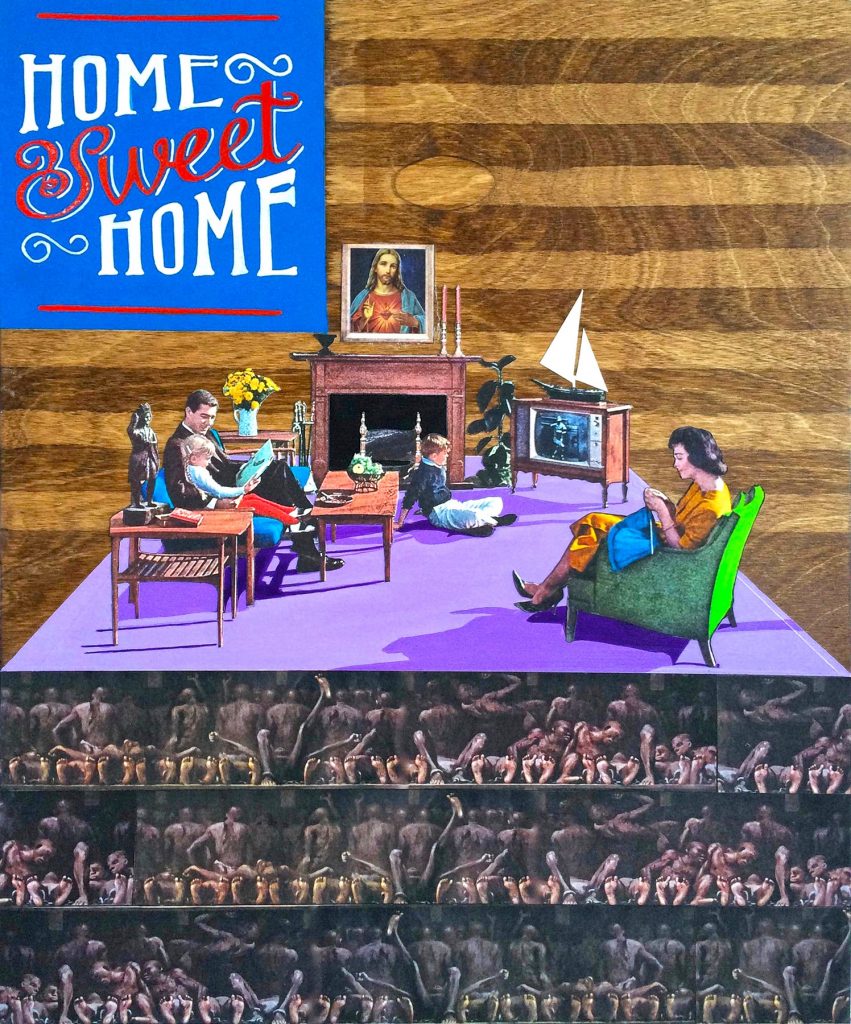

AL: I feel like I’m looking at pieces of an old Life magazine when I view some of your pieces.

MH: Yeah, Life was the be-all-end-all representation of Americana. I like using the old imagery—you can very quickly evoke a particular time, an era. I juxtapose the old imagery from the golden age of advertising that was designed to communicate the paradigm we’ve already bought into. I want people to question what’s going on in my scenes—it messes with the grid; creates a glitch in the mind.

AL: A glitch?

MH: My work is intended to be subversive; I use the old images as wholesale representation of what we’ve bought into; especially if you consider how African Americans were presented.

What’s Next?

AL: What’s on your mind?

MH: While my next body of work is in its embryonic stage, I have continued to explore how I might get my work out to a larger audience, to keep expanding in the collective consciousness these messages so I can help people toward being the change they want to see. I’m interested in the productivity of my work. I sold a piece [recently] to an individual who is a part of the Democratic Socialists of America. He said the piece was going to hang in their offices here, as it depicts the messaging to which they endeavor to adhere. This connection gave me a serendipitous introduction to an artist interested in projecting my work in public spaces—onto the sides of buildings here—subvertising! I’m excited about this opportunity to get the work and the message out to a larger audience. This is what I want to continue to do; to affect the collective.

San Francisco, California-based artist MARK HARRIS has combined his passions for social justice, activism, and art making to create a unique visual vocabulary that he uses to engage his audience on some of the most critical issues facing society today. He has expanded his practice to include mentoring at-risk youth through art education programs.

Facebook: @TheArtivistSF

Instagram: @markharrisart

ANDREA LYNN‘s writing is activated by an eccentric curiosity that collects ideas and details. The training and temperament of a journalist, her natural inquisitiveness is concentrated on exploration of the human capacity to remember and to forget. She dreams of an empathetic collective.

Featured image: Mark Harris, “Original Gangsters,” mixed media collage on paper, 2014.