Born in a refugee camp in Germany after World War II, JOHN Z. GUZLOWSKI came to the United States with his family as a displaced person in 1951. His parents had been Polish slave laborers in Nazi Germany during the war. Growing up in the tough immigrant neighborhoods around Humboldt Park in Chicago, he met hardware store clerks with Auschwitz tattoos on their wrists, Polish cavalry officers who still mourned for their dead horses, and women who had walked from Siberia to Iran to escape the Russians. In much of his work, Guzlowski remembers and honors the experiences and ultimate strength of these voiceless survivors.

Over a writing career that spans more than 40 years, Guzlowski has amassed a significant body of published work in a wide range of genres: poetry, prose, literary criticism, reviews, fiction, and nonfiction. His work has appeared in numerous national journals and anthologies, and in four prior books. Guzlowski’s work has garnered high praise, including from Nobel Laureate Czeslaw Milosz, who called Guzlowski’s poetry “exceptional.” Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded, his book of poems and essays about his parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany, won the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation’s Montaigne Award. He is also the author of three novels.

It is our pleasure to share with you our intimate interview with Guzlowski, but before we dive in, please watch the video below and read the three poems we’re featuring on The Nasiona, which were originally published in the critically-acclaimed Echoes of Tattered Tongues. These examples will help you get a sense of what is to come.

And now, the interview.

Julián Esteban Torres López: Imagine you are a character in a story you are writing. How might you introduce yourself?

John Z. Guzlowski: This is the hardest question I’ve ever been asked in an interview!

How would I introduce myself? Generally, I write in the third person, so I think I would say something like this:

He was an old guy who didn’t know he was old, or at least he didn’t know it too often. When he didn’t know it, he would think about the trees around him, the sparrows waiting to sing, the dawn shaking him awake and whispering, “Open your eyes honey, it’s a new day waiting for some words to describe it.”

But when he knew he was an old guy, he would brood about stuff old guys brood about, aging, death, dying, the silliness of the world going on around him. He would brood about that and try to put some words together about all that so he could make some sense out of it before it was too late.

JETL: Your book Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded is excellent on so many levels. It is raw, moving, real. The writing is compelling. Hypnotic. You speak with the honesty of memoirs and the haunting voice of a refugee. Your poems and prose unearth the essence of the human condition. Storytelling at its best. One thing that really stood out for me was that you tell a story about World War Two I hadn’t really heard before. To help set the setting for your book and for your family’s experience, can you tell our readers a little bit about slave labor camps during the war and the refugee camps after the war?

JZG: Echoes of Tattered Tongues focuses its memoir pieces and poems on my parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany. I give a lot of talks and readings about this, and I always find myself explaining why there was slave labor in Germany during the war.

The reason is pretty straightforward. Most of the German men were out trying to conquer the world, and they didn’t have time to do the work they would normally do. They couldn’t work in the factories making tanks and bombs, and they couldn’t work on the farms to produce food for themselves and the rest of the people of Germany.

So what the Germans did as they invaded countries was to scoop up civilians in those countries and turn them into slaves back home. The Germans liked to call this “forced labor” but my mom and dad—who were both slave laborers—always used the Polish word for “slave” when they talked about how they and the 2 million Poles who were taken to Germany to work in the factories and on the farms there were treated.

Another thing I have to explain during poetry readings is that my parents weren’t Jewish. They were Polish Catholics. The Germans felt that they were subhumans, almost like mules. The Poles, of course, weren’t the only ones. By the end of the war, when we finally beat the Germans, the Allies found about 12 million slave laborers there. They were people from all the countries of Europe. A lot of them were in concentration camps that had been built around factories or farms.

My parents were in those camps. My dad spent 5 years in Buchenwald, and my mom spent almost 3 years in some sub-camps of Buchenwald.

What was it like in the camps? Every year about 25% of the slaves died of starvation or brutality. They worked 14-16 hours a day, most days, on about 600 calories of food. When my dad was liberated he weighed 70 pounds. When my mom first met him she said she wasn’t such a prize but that he looked like two shoelaces tied together.

Let me say one more thing about those slave laborers. After the war, the UN tried to sort out all the slaves and they were put in refugee camps until the UN could get them some place safe. It took my family 6 years to find a country that would take us in.

JETL: Another thing that stood out for me about your book is that it went beyond the statistics we’re used to hearing about the war. You humanized the data. Your stories about your parents keep the memories of the victims of the war alive. Can you tell our readers a little bit about your mother and father?

JZG: For me, numbers are never enough. If you Google WWII and statistics, you’ll come up with a lot of numbers. You’ll find out that the Nazis murdered 6,000,000 Jews. You’ll find out that altogether 52,000,000 civilians died in the war, more or less. You’ll hear that 20 million died in Russia, 7,000,000 died in Germany. 2 million in Japan. I was surprised to hear that Yugoslavia, a country that I don’t think much about anymore and probably never did, lost 1.7 million people. The country my parents came from was Poland, and it lost 1/6 of its population. Before the war, there were 36 million Poles; that means about 6 million died. In Warsaw, the capital city of Poland, a quarter of a million civilians died during a 60-day battle to throw the Germans out in 1944.

That’s a lot of numbers, but there are many, many more associated with the war.

I read those numbers, and it’s hard for me to realize what they mean.

I have a friend who’s a professor of mathematics, and she tells me that most people can’t imagine and can’t visualize a number greater than 1000.

What I’m trying to do in my writing is to translate all of those deaths, all of that suffering into numbers that people can imagine, can visualize. My mother, for example, would be one, my dad would be another one. That’s 2, the two my poems are about.

My mom and dad before the war were typical Polish farm kids. My dad was 18 when the war started, my mom was 17. He lived in northwestern Poland, she lived in eastern Poland.

My dad was captured in 1940. He had gone into his village to buy some rope one Saturday morning. The village had been surrounded by the Germans, and they rounded up people. They were gathering people up to work in the factories and farms of Germany. My dad was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp, and he spent the next 5 years there as a slave laborer. During that time he saw a lot of the boys from his village killed. They were hanged, beaten to death, crucified, starved. One time my dad complained that he couldn’t work without more food, and a guard clubbed him into unconsciousness. When my dad awoke, he was blind in one eye.

My mom was captured in 1942. The Germans came to her village. She saw her mom, her sister, and her sister’s baby killed. My mom fled into the woods near her home, but she was captured and put in a boxcar with the other girls from her village and sent to Germany.

My parents met at the end of the war just before liberation. My dad was on a death march that was traveling by the camp my mom was in. The German soldiers who were guarding them both fled at that point because they were afraid of the advancing Russian army.

I think about this moment a lot. I think about what it must have been like for my mom and dad and all the millions of others, people who hadn’t experienced a single human loving touch in so many, many years. They must have felt overwhelmed with hope at that moment of coming together and feeling hands and bodies and faces that were loving and not hating.

After that, my parents spent 6 years in a UN refugee camp waiting for some country to open its doors to them. They—like lots of others from Eastern Europe—felt they couldn’t go back home because home was now controlled by the Russians.

I was born in one of those refugee camps in 1948 and came with my parents to America in 1951.

JETL: How has your parents’ traumatic experience as slave laborers in Nazi Germany during World War Two echoed through time?

JZG: The war never ended for my parents. It was always there.

My father had terrible nightmares all his life. I remember when I was a kid hearing him screaming in the night about how the Germans were coming to drag him to the ovens. I would run into his bedroom to try to wake him, and it was always hard to do.

When he was awake, his thoughts were always about the war. He couldn’t control himself. He would see something or someone and the war would be there right in front of him. I remember one time when I was a boy, about 12 years old, bringing a friend over to our house for the first time, and my dad saw this friend and said, “He’s a German. I don’t want him in the house.” This surprised me so much because my father was a loving person. He never raised his voice or got angry at anything or anyone, but this German-American boy coming into the house triggered memories my father couldn’t deal with. These memories also drove him to drink. For most of his life, he was an alcoholic. The drinking didn’t help, of course. When he drank, all he could talk about was what the Germans had done to him and his friends and so many others.

My mother almost never showed any kind of signs that she had been affected by the war. Even though she had experienced terrible things and seen terrible things done to so many people, she didn’t have nightmares, she didn’t drink, she didn’t throw my German friends out of the house, she didn’t grieve. My mother, in fact, didn’t show any kind of emotion, not grief, not love, not hatred, not joy. She also—for decades after the war—refused to talk about what she had experienced and seen in the war. The only proof she showed that she was affected by the war and the way she was treated was her anger when something wasn’t done right. If my sister failed to wash some dishes or cook a meal correctly, my mother would beat her with a broom handle. My sister and I used to say that my mother learned parenting from the German guards in the camp.

JETL: How has your experience born in a refugee camp after the war and being a displaced person echoed through time?

JZG: It shaped me in a lot of ways. I think the most profound effect was that my father started telling me stories about what happened during the war very early on, probably when I was 4 or 5. He would have a few drinks and call me over and start telling me about women being stabbed in the breast by German soldiers. He would tell me about his friends who had been crucified or frozen to death by the guards. I’ve never shaken these stories.

For a long time, I tried to shake them off. And I tried to shake off the whole experience of being a refugee and a displaced person. I grew up in a neighborhood in Chicago that was made up of lots of refugees. Many of my friends were refugees, and their parents were like my parents—fucked up by the war. I saw my friends experiencing the same kind of cruelty from their parents as my sister and I experienced from our mother. In fact, in some cases, it was much much worse.

There was this and then there was also the way we were viewed by the non-refugees in our neighborhood in Chicago. We were seen as dirty and dumb. Officially, according to the UN, we were DPs, Displaced Persons, but our neighbors told us repeatedly that DP meant dumb Pole and dirty Pole. We were the people who nobody wanted to rent a room to or hire or help. We were the “wretched refuse” of somebody else’s shore, dumped now on the shore of Lake Michigan, and most people we came across in America wished we’d go back to where we came from. And that we’d take the rest of the Poles with us.

As a kid growing up, I felt hobbled by all that sorrow and all that difference, all that apartness. I didn’t want to be a “displaced” kid. I just wanted to be an anonymous American kid, a “placed” person. School helped me get away from all of that DP world. In college and grad school, I turned to books and literature, a world where there were no survivors, no refugees. During all those college years, I seldom thought about the lives my parents had lived during the war. At least not until the very end of my college career. I was a year short of finishing my Ph.D. dissertation on postmodern American fiction when I wrote my first poem about my parents. I guess you could say that I had to be “placed” before I allowed myself to be “displaced.” I had to overcome their world before I could enter it. But even then, it was a slow process. It took me another 25 years to write the poems that became my first book of poems about my parents: Language of Mules.

JETL: Given that you deal with some very real and traumatic experiences, how difficult was it for you to write this book?

JZG: How difficult was it to write this book? I started in 1978. This book came out in 2016. I wrote the first poem about my parents and I never envisioned another poem at that point. Then a few years later I wrote a second poem about my parents, and then the following year I wrote two or three, and then the next year a few more.

The writing itself wasn’t difficult emotionally. I would remember something that my father said, and I would write it down and then flesh it out. My writing at that point was mainly about remembering the stories my parents told, and setting them down in such a way so that someone reading the poem would feel what my mom or dad was trying to convey about their experience when they told me the story.

It was largely a process of memory for me, and it’s a process that’s ongoing. Forty years after I wrote the first poem (a poem by the way about remembering) I am still remembering things my mom and dad said and setting them down. Here’s a small piece I wrote today, a sort of haiku about something my dad saw and heard in Buchenwald toward the end of the war:

Buchenwald — A Haiku

Behind the winter wire

a Russian soldier sings —

his voice a violin

For me, the difficulty comes when I have to present these poems about my parents at a poetry reading or a presentation. Reading them in front of an audience, I hear again my parents’ voices telling me the stories that became these poems. I hear my dad talking about the bayonet thrust into a young girl’s breast or I hear my mom talking about how she would tell the German soldiers that she had a venereal disease so that they wouldn’t rape her and how they would laugh in disbelief and rape her anyway, again and again.

That’s the hard part for me. Telling these stories and hearing my parents’ voices again.

JETL: How did you learn about your parents’ stories?

JZG: My dad was always telling me stories of the camps and the war. I don’t remember a time when he didn’t. My mother wasn’t like that. She didn’t start telling me the stories until I was much older. In fact, it wasn’t until after my dad died that she started telling the stories. I think by that time she realized that the stories needed to be told. I remember one time watching a TV show. It was an interview with a Holocaust denier. My mother turned to me after the show and said, “He wasn’t there.” I think it was soon after that that she began telling me her stories.

JETL: Why did you write Echoes of Tattered Tongues? Was there a reason?

JZG: The reason? I never intended to write about my parents. For a long time when I was first in college, my dream was to write science fiction novels. I wanted to be the next Robert Heinlein or Isaac Asimov. I wanted to write about silver spaceships moving through the endless darkness of space toward a jeweled planet of creatures not even I could imagine. And then in grad school, I became obsessed with writing about literature and all the great writers of the American past. I never wanted to write about my parents and their tortured lives and memories. In fact, it was the last thing I wanted to write about. But writing doesn’t always ask you what you want to write. In my experience, it tells you to write, and you must write what it wants you to write.

There are reasons of course. I think it’s important to remember these stories and pass them down. So many mothers and dads and children died in WWII. If my telling one of these stories can prevent even one death, I would consider that justification enough for writing.

JETL: Do you ever envision what your life would have looked like if there was no World War Two and your parents would have met in Poland, gotten married, and had you and your sister there, instead? If so, what do you imagine that life would have been like?

JZG: I can’t imagine it. After spending 3 years in a concentration camp, my uncle went back to Poland after the war. He traveled on a UN-protected train. He got off the train and was arrested by Russian soldiers and sent to a concentration camp in Siberia. He died there.

But life in Poland under the communists who took over after the war? It would have been very hard. If my parents had been able to return to Poland, they would have become farmers, probably on a small family farm north of Poznan. It would have been a difficult life. When the Germans were finally thrown out of Poland, they left a country in ruins. One out of every six Poles had died in the war. I’ve seen officially UN photos of Poland in 1946. It’s a ghost land.

But if we had gone back? Perhaps after 30 years of working on that farm, my parents may have had enough money to buy their own 20-acre farm. They would have sent my sister and me to school. But I doubt that I would have ever gone to university or written anything about my parents.

The prospect of imagining life in Poland after the war is so bleak.

JETL: Can you share a happy childhood memory that still brings a smile to your face?

JZG: Oh sure, of course.

My parents loved to take walks in one of the great parks that Chicago has. Almost every Sunday, my mom and dad would take my sister and me to a park where we would see flowers and trees and sailboats and a zoo full of elephants and bears. And sometimes we would go to a beach on Lake Michigan and sit on a blanket and eat my mother’s wonderful Polish food and then go swimming in the lake until it was so dark that we would have to rush home to get to bed.

JETL: Readers sometimes hope their favorite authors share some of their favorite things or hope they can relate to them on a human level. I have here some questions for our readers to get to know you a little better as a person.

What does your writing process look like?

JZG: I write a lot. I try to write for a block of 4-5 hours each day. But even when I’m not writing, I’m writing. I take down notes for ideas for poems or stories or essays.

The 4-5 blocks are a lot of fun. I am always working on some project. Either a new poetry book or a new novel. Or I’m revising one or the other. Or I am doing the final editing for a book.

I enjoy doing all of this.

What I hate about the writing process is all of the stuff that doesn’t involve writing. I hate submitting poems or stories to magazines, I hate receiving rejection letters, I hate looking for agents and publishers. That stuff eats up so much time that I would rather be spending writing.

JETL: What’s your secret talent?

JZG: If I tell you, I’ll have to kill you.

Just joking.

Listening to the muse. She always says put down a word, any word, and I’ll take it from there.

JETL: Do you have a writer ancestor (related or not related)? Someone’s whose writing you relate to/with?

JZG: I’ve loved a lot of writers. But I think the two that most shaped me were Jack Kerouac and Walt Whitman. For years, I carried a book by one of these writers at all times. When I was riding my bike, or taking a bus to work, or hitchhiking across America, I had a copy of Whitman’s Song of Myself or Kerouac’s On the Road or one of their other books in my pocket. What moved me in their writing was that they both had a real sense of how chaotic and unforgiving life could be, but still they both had a dream that there was beauty and love and forgiveness in the world.

JETL: What makes you angry?

JZG: Killing. Killing. Killing. In some ways, it feels that the terrors of WWII are still here, still alive around me.

I live in the US where there is a mass killing every couple of weeks. About 20,000 people are murdered here every year. And the U.S. isn’t the only place where there is killing.

The killing in Syria? The killing in Iraq? The killing in Mexico? The killing in Afghanistan? The killing in Myanmar? In Ethiopia? In Darfur? In Somalia?

There are 4 countries where armed conflicts have killed at least 10,000 people so far this year.

There are 14 countries where armed conflicts have killed at least 1,000 people so far this year.

This makes me angry and powerless.

I sometimes feel that killing is built into our DNA, that killing seems too often to be the first solution we turn to to solve any problem.

JETL: What do you regret doing or not doing in terms of your career?

JZG: I spent 35 years of my life focused on academic writing, the kind of writing that professors do, with research and footnotes and references to obscure academic critics no one remembers. I published dozens of such academic articles. It was a waste of time and kept me from doing the kind of writing I should have been doing.

JETL: What’s your favorite thing to do when you’re not writing?

JZG: I like to read a book, walk around a park, have coffee in a café, listen to the voices there.

JETL: Who are your influences?

JZG: I mention Walt Whitman and Kerouac above, but there are so many others. I’ve always loved reading and I feel that a lot of writers have influenced me in a lot of ways. A short list would include T. S. Eliot, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Emily Dickinson, John Steinbeck, Dostoevsky, and Saul Bellow.

JETL: What kind of music do you like?

JZG: American Jazz, blues, folk, ’60s rock and roll, Beethoven, American songbook. All kinds of music.

JETL: Do you have any food taboos?

JZG: I’m a vegetarian. I haven’t had meat in 40 years.

JETL: What are you working on right now to get better at or improve?

JZG: I’m working on 4 books of poetry right now: a book about a Japanese Buddhist monk, a book about all the stupid things I’ve done in my life that I’m ashamed of telling you about, a book about what God means to me, and a book about the writers I love to read.

They are all in various stages of composition, but I hope to get a couple of them published this year.

JETL: What do you think the world needs more of?

JZG: Love, peace, hope.

JETL: Is there a celebrity you really want to meet?

JZG: No. I’m not really interested in meeting celebrities. There are actors, singers, and writers who I admire very much, but I honestly wouldn’t cross the street to meet one.

JETL: What do you wish you knew when you were 20 that you know now?

JZG: I wish I knew that I could write. I would have started when I was 20 and not waited until I was 55.

JETL: If you’re in a new city, what do you like to do?

JZG: I love going to art museums. If I were in a city I had never been in, I would immediately go and see what kind of art the city likes to look at.

JETL: Do you consider yourself an introvert or extrovert?

JZG: Both.

JETL: What’s your favorite thing to cook, and why?

JZG: Soup. I like vegetable soup. Bean soup. I like cooking it because it always brings my mother back to me. She loved to make soups, and I loved to help her.

JETL: If you want to be alone, where do you go?

JZG: My study. I can spend the whole day there and my wife will seldom come down or call for me. She knows I’m working.

JETL: Coffee or tea, or neither?

JZG: Coffee in the morning. Tea in the afternoon. Red wine in the evening.

JETL: Dog or cat, or neither?

JZG: Cat. I have had cats all my life. I’ve never had a dog, and I probably will never have one. My wife Linda is allergic to them.

JETL: Do you prefer to work in the morning, afternoon, or night?

JZG: I used to love to work for a couple hours in the morning revising, and then four hours in the afternoon writing new stuff, but now what I tend to do in the morning is exercise and do chores around the house. I leave my writing for the afternoon. I start about noon and go until 5.

JETL: What’s your favorite city?

JZG: The city I grew up in. Chicago. But not the Chicago of today. The Chicago of 60 years ago. A city of immigrant and refugee dreams. A city of poets and writers. Of words describing every cool breeze and every sunny day.

You can follow John Z. Guzlowski on Twitter, Facebook, and his blog.

And don’t forget to read the three poems we’re featuring on The Nasiona, which were originally published in Guzlowski’s critically-acclaimed Echoes of Tattered Tongues.

Winner 2017 Benjamin Franklin GOLD AWARD for POETRY.

Winner 2017 MONTAIGNE MEDAL for most thought-provoking books.

“A searing memoir.” ― Shelf Awareness

“Powerful…Deserves attention and high regard.” ― Kevin Stein, Poet Laureate of Illinois

“Devastating, one-of-a-kind collection.” ― Foreword Reviews

“Gut-wrenching narrative lyric poems.” ― Publishers Weekly

“Taut…beautifully realized.” ― World Literature Today

Julián Esteban Torres López is a Colombian-born journalist, researcher, writer, and editor. Before founding The Nasiona, he ran several cultural and arts organizations, edited journals and books, was a social justice and public history researcher, wrote a column for Colombia Reports, taught university courses, and managed a history museum. He’s a Pushcart Prize nominee and 1st place winner of the Rudy Dusek Essay Prize in Philosophy of Art. His book Marx’s Humanism and Its Limits was BookAuthority’s Best New Socialism Book of 2018. His micro-poetry collection Ninety-Two Surgically Enhanced Mannequins is not as serious in tone as his forthcoming book Reporting on Colombia: Essays on Colombia’s History, Culture, Peoples, and Armed Conflict.

Twitter: je_torres_lopez

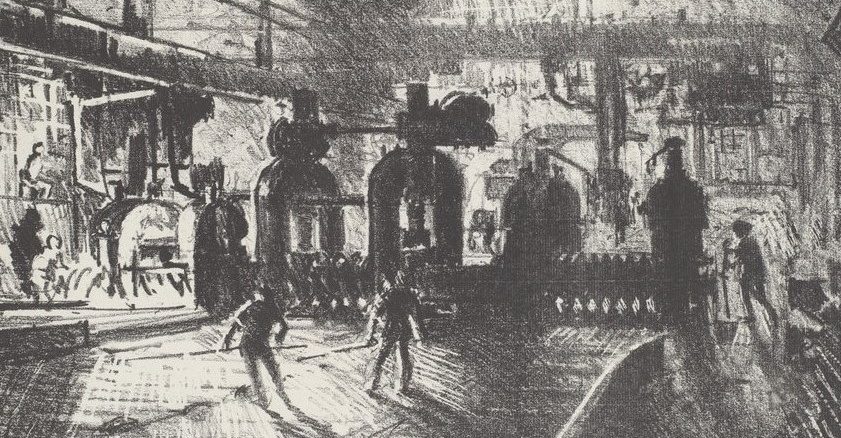

Featured image: Joseph Pennell, “In the Jaws of Death, Rolling Bars for Shells,” lithograph, 1931, Rosenwald Collection, National Gallery of Art.