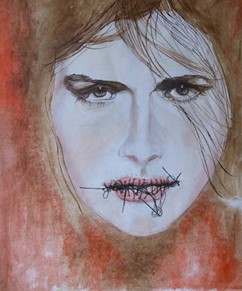

Speak, it’s called. A small portrait in oils. The head of a young woman, not yet twenty, with soft melancholy eyes.

There’s a needle sticking through the canvas with an untidy tangle of thread, the colour of dried blood, dangling from it. The work of the needle is clear to see — a ragged mess of stitches running in jagged lines from upper to lower lip. I left the needle there, piercing the tender flesh of the mouth, as any woman pausing between stitches does. This is an artwork that will never be entirely finished. She could not speak when I took up my brush and laid down the first strokes but things are different now — threads can be unpicked, voices recovered.

Me at nineteen. Coming up for air, emerging from the turgid waters of puberty. A long way from home.

This is my first share house. I like everybody. I don’t care who they are — I like them. I’ve deaded my instincts, put a gag on every whispered apprehension, every slither of fear, distaste, dislike. I’m deaf to my own shudders, the ever-so-slight recoil I feel in the company of certain people. The only thing that matters is what the others think of me. I want to belong to this tribe. I’ve decided, arbitrarily, that they’re it, they’re my people. They’re a little older and a lot more savvy than I am — university graduates — while I haven’t even started on that journey yet. They smoke weed, go to demos, throw parties. All of Melbourne comes to these parties and I find myself rubbing shoulders with journos, actors, painters, mystics.

I’ve stumbled through the gates of heaven and somehow dodged the door bitch. Sooner or later I know I’m going to be found out, exposed as the unworldly little imposter I really am and hurled back into the insipid realities of my previous life. But for now I’m cool. I fit in. At least I think I do. But I’m never really sure. I’m hyper-vigilant for the least little sign that I’m saying the wrong thing, wearing the wrong gear, befriending the few odd bods the others quietly roll their eyes about.

People are always dropping in and out of the house. It reminds me of home. We used to leave the key in the front door. A steady stream of visitors was always coming and going. But these visitors aren’t nosy neighbours coming over to gossip, or dreary relations, or school friends. These are stand-outs — they come to argue politics, to play music, to talk art and philosophy.

I drift in and out of other people’s houses, too, going to one party after another, dropping in for dinner or a joint. I never refuse an invitation — that’s a luxury I can’t afford. I won’t risk being thought snooty or uncool.

Danger has a smell, a shape, a sound. It’s very distinct. When you’re listening for it. But when you’re crazy for approval, manic to belong, it blurs and blunts your senses.

‘Get down!’ you tell your gut, not yet aware that it’s the best surveillance apparatus you’ll ever have. You’re so focussed on trying to impress others that you’re oblivious to the nudges and jabs within telling you to walk away, deaf to the alarm bells that startle your senses when real peril looms into view.

Ella rode a motorbike, a novelty for girls in the 70s. She was odd, a bit on the rough side. I never felt comfortable around her but she was a close friend of my house-mate, Tamara, and impossible to avoid. The two couldn’t have been more dissimilar. Tamara was studious, quiet, bohemian; Ella coarse, moody, unpredictable. Now and then, she rolled up at our parties with her bikie flat-mates. A couple. Mick was in his mid-twenties. He wore leathers with a gang insignia on the back. His girlfriend was a lot older, reed-thin, condescending.

Ella, Mick and his girlfriend. These people inhabited one universe and I another. We had nothing in common but a few mutual acquaintances. But when Ella invited me for dinner at her flat, I swallowed my surprise and said yes, the way I said yes to every other invitation, despite feeling how strange it was that someone who had barely ever looked at me sideways would want to cook for me, despite wondering why she hadn’t asked Tamara who was standing right there, despite sensing that something was not quite right here.

I still hate to think of myself threading my innocent way through the back streets of Carlton that night, stifling the dread that was gathering in the pit of my stomach, the dread that I took to be nothing more sinister than boredom at the prospect of spending an evening with Ella.

It was quiet in the flat. There was just Ella and Mick. The condescending girlfriend had gone away. Ella disappeared into the kitchen and stayed there for a long time, shoving away my efforts to help and only emerging at intervals to slam plates and dishes down before us and laugh in that manic way of hers. Mick was a man of few words. From the little he did say, it quickly became apparent that he had nothing at all of interest to say for himself. By the time Ella finally joined us at the table, the atmosphere in the flat had become oddly off-kilter and I couldn’t wait for dinner to be over so I could take myself off home.

‘I better be heading off. Getting dark out there.’ I imagine that’s what I said as I collected my bag at the end of that unremarkable meal.

My memory of what happened next is a great deal clearer. The stillness in the room. The look that passed between those two, seated unmoving at the table. This was not at all how it was meant to end.

‘You can’t go!’ Ella shouted, but Ella shouted so often that I didn’t raise an eyebrow.

‘Mick really likes you.’ Her voice had softened but the grin she gave me made my stomach turn. ‘He wants to have sex with you.’

I wish I could say I froze inside when I heard that. I didn’t. Men, young and old, said things like that on a regular basis in the 70s. Perhaps they still do. Very few girls my age would have been shocked. That isn’t to say it wasn’t mortifying and uncomfortable in the extreme. But surprising? No. What was surprising and totally disconcerting was that the words had come out of another woman’s mouth on behalf of a man who was standing right in front of me. As though he was incapable of telling me himself. I looked up at Mick who gave a dopey laugh and nodded his head.

‘Bad luck,’ I said flatly to Ella, not to Mick. Mick hadn’t asked. ‘I don’t want to have sex with him.’ And I headed for the door.

But Ella stepped in front of me, blocking my path. Only then did I feel an icy rush of terror race through my veins.

‘Why not?’ she exploded. ‘Look at him! He’s gorgeous. Why don’t you want to have sex with him?’ Outrage and disbelief were written all over both of their faces. Mick still hadn’t uttered a word.

I dodged around Ella and was at the door in a flash but so was Mick and, before I could grapple with the latch, he had unearthed a rifle from somewhere and had it pointed at my head.

Dear Jesus. I simply don’t have the vocabulary to explain how it feels to have the muzzle of a rifle resting on your temple in the certain knowledge that the person wielding that weapon is both angry and stupid.

‘Let me fuck you or I’ll shoot.’ All of a sudden Mick had found his voice.

‘Go ahead and shoot. I’d rather be dead than let you fuck me.’ I didn’t have to think — the words just spilled out of me. How cool and confident they look on the page. How brave and utterly contemptuous of the brute who towered over me. The reality was vastly different. I was shaking so violently I could barely stand upright, my throat was dry and I was gasping with sheer terror.

I don’t think Mick expected me to refuse. He was a big hunk of a guy and he loved himself. Ella loved him, too. Even then, through the thick fog of my fear, I caught a glimpse of the perverse dynamics that had sparked the situation. Mick didn’t want Ella but she wanted him. If she couldn’t have him, at the very least she could try to procure a woman he desired. That way, he’d be grateful, he’d see that she was on his side, he might even come to want her one day.

I am trembling a little as I write this. I am nineteen again. I remember that I sobbed. ‘Let me go. Just let me go.’

He didn’t. Not at once. He was a bikie, a tough guy, he couldn’t afford to look like he could take a knock-back so lightly. And so I was compelled to stand there, facing the door — oh that timber door, I can still see it every line of it and feel the tantalising proximity of the latch – with the rifle poised on my temple while the two of them talked about it for ten or fifteen minutes. At least that’s how long it felt. Perhaps it was only two.

I don’t remember what they said in those long minutes but, in the end, Mick put the rifle down, defeated, and I fumbled and scratched crazily at the latch, got the door open and ran. Down the stairs. Out into the street. Home.

In ‘73 it wouldn’t cross your mind to call the police over something like that. That was just how it went. I went home and forgot it. Almost. There were odd surges of panic now and then. The merest glimpse of a man in leathers could drain the colour from my face and I thought twice before entering any building with a motorcycle parked outside.

A couple of years after the event, I saw Mick and his girlfriend walking in the city. My heart raced and I stopped dead in my tracks. Neither of them noticed me standing, head reeling, only metres away, numbly trying to reconcile the picture they presented with the horror of that night. A golden couple they seemed, tall and beautiful, calmly connected to each other in a way you sensed could never be sundered. For a split second, I thought of running up to her, blurting out the whole story, exposing him, but the impulse shrivelled and died almost as soon as it arose. I knew I would be wasting my time.

Then the memory closed over. For decades it remained so deeply buried in the farthest reaches of my mind that it seemed to have vanished altogether.

Out of the blue one day something impelled me to tell a friend. Secrets have astonishing power, the power to strip away decades of accumulated experience. Open up an untold, closely guarded secret and you are briefly but most potently at its mercy. All of the sensations and emotions embedded in that very private moment of time exploded and I was thrust back into the brutal truth that I had been fleeing all those years. What I recalled seemed lurid, grotesque, unbearable to contemplate, a chapter of my life from which I would never recover. I was shocked and confused to feel my body shaking convulsively as I struggled to get the words out, baffled to find myself in the grip of fear so intense that what I was describing might have happened only yesterday. Yet only in the telling did the horror begin to dissipate and its ferocity to dim.

What emerged as the haze began to disperse were answers to the puzzle that I had become to myself. Unlocking that once so firmly bolted door showed me how one single evening in my young life shaped all of my subsequent responses to any perceived threat. How alert I became to danger in any form, how closely I scrutinised acquaintances and strangers alike, coolly assessing their potential for harm. These are survival skills it took many of my peers years, sometimes decades, to develop. And here’s the twist. That episode catapulted me into adulthood, showed me the limits of my endurance, taught me that young and female doesn’t have to equate to compliance in the face of intimidation. But there are gentler, kinder ways to learn the same lessons.

Looking back, I still marvel that I had the courage or craziness to hold my own ground that night. Physically, I’m a coward, terrified of spiders, heights, deep water, storms, high speeds, getting on a bicycle, treading on rough or slippery ground – anything the least adrenaline inducing. And I go out of my way to avoid these things. I fear certain kinds of people, too, but the mere whiff of threat from them — to me or to anyone vulnerable in my vicinity — has the curious effect of making me dig my heels in hard and stand up to them, regardless of the risk. Awakening that sleeping giant also helped me to understand why I lost my appetite for making demigods of mere mortals so young. In a sense, it both dirtied and deepened my view of men and women alike, for Ella was complicit in what transpired that night. I could no longer be seduced by appearances, lost that aching need to belong and became deeply attuned to my own instincts.

There might well have been a grimmer outcome. It’s an indisputable fact that resistance can escalate violence as surely as it can cut it short. The long-running debate about which response to a threatened assault will inflict the least damage — resistance or compliance — ignores the reality that every circumstance is as distinct and unique as the individuals involved. But I wonder how much choice any of us really has when our lives are imperilled and we don’t have the luxury of time to consider our options. I know I acted purely on instinct. Perhaps I intuited that this was a man whose threats were nothing more than bluff. I suspect I was just plain lucky. I was scared, but not scared enough. Mick was a brute, but perhaps not enough of a brute to take it any further.

Paulette Smythe

Paulette Smythe is a Melbourne writer and visual artist. In her work she seeks to capture some of the mystery and paradox that lie beneath the surface of ordinary life. Her work has appeared in Bewildering Stories, Verandah, Eureka Street, the Shuffle anthology and Prometheus Dreaming.