I went through my childhood unloved — almost entirely — but luxuriating in love for my adulthood thus far. The juxtaposition between wanting to be loved as a child, feeling a literal figurative void in my little heart, and having an abundance of platonic and romantic love as an adult has been accompanied by various geographical, social, political, and linguistic changes in my life. The last of which remain of interest to me: even though I only spoke Arabic in my childhood, English is my primary language now, and a part of me wonders if I can experience love differently if the language through which I express it changes; that is if love will occupy a different space in my psyche if I were to ever love in Arabic.

I am a stranger to being loved in Arabic — utterances of both platonic and romantic love I have only heard in English, and I still cannot bring myself to proclaim love in my mother tongue, even to my Arabic-speaking friends. I hold both my languages dearly to my heart but English is the only language through which I learned to love and be loved, rendering Arabic a language with experimental dimensions to me: there is a yearning within me to speak to and about love in Arabic, to utter Arabic terms of endearment I learned from songs and poetry, sentences of platonic and romantic love, letting syntax bid farewell to the last unresolved wish of the unloved child I once was.

I can only think of one moment at which love was spoken of in Arabic: I was twelve years old and I was in the car with my father. My parents had been divorced for a while by then and I was living with my mother. My father had come to our building to talk to me. I was drenched in sweat already, as I had always been in his presence, dreading his company as I did my mother’s. I had not seen my father for weeks and nothing remarkable had transpired to necessitate a visit or a conversation of any kind.

“Listen, Nofel,” he said, seeming to defeat his perpetual stutter this time. “There are some obligations I have toward you as a father,” he asserted, staring into my eyes. “I will still perform these obligations, but I want you to know that I no longer love you.”

“OK,” I said, looking at him, unsurprised — grappling with an amalgamation of emotions I will never be able to name.

He gestured for me to leave the car.

I did not think of this conversation for years after. I never assumed that my father loved me in the first place and a part of me understood that such a revelation could only be reflected on once I experienced love, which I had not then, not even toward myself. I realized even then that I would never know what it means to stop loving if I did not know what it truly means to love.

Now that I have both fallen in and out of love with people, platonically and romantically, I have been looking back at this moment often — with peculiar fondness: it is the only simultaneous confession of falling in and out of love to which I have been a witness, for a declaration of no longer being in love when love was never expressed to begin with is nonetheless a divulgence of love. I now realize that for someone who kept all his life a secret from me, it must have been burdensome for my father to tell me that he no longer loved me while admitting to have loved me, at least for some time. I wonder which proclamation was more challenging and for how long he grappled with revealing to me that he did not have love for me.

I have never loved my father. As much as I tried to delude myself that I did as a child, I now know — almost certainly — that I was incapable of loving him. He simply did not deserve my love, albeit I am definite (and hope) he has been worthy of someone else’s love. I have not seen my father for years and I have no plans of ever connecting with him. The last time I saw him at sixteen, around eight years ago, I had a premonition I was not going to see him again and I asked him to give me a book of his to remember him with. He had more than a thousand books, most of which he had not read, but he refused. I went inside his office and stole one of his Arabic books. I have recently lost it. I am sure it is scattered in a box somewhere, covered with years and years of dust, waiting to be picked up and read — numerous Arabic sentences longing for a new experience, for a poetics of liberation, of love.

*

A longer version of this essay previously appeared in Arabic on jeem.me.

Nofel

Nofel is a Canadian poet and essayist. His writing has recently appeared in Yolk Literary Journal, Open Minds Quarterly, and House: Queer Black and Brown Creative Anthology.

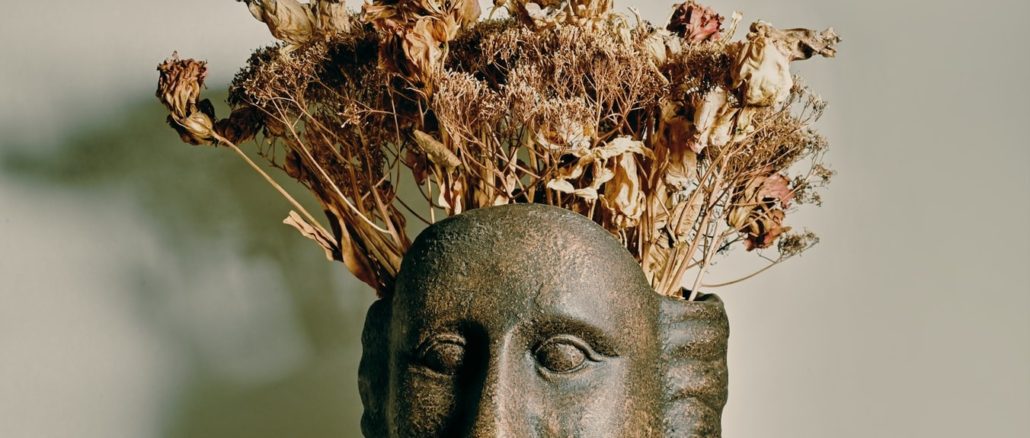

Featured image: Artwork by Girl With Red Hat on Unsplash.