If puppies don’t socialize during the first few months after birth when behaviors are relatively easy to modify, they subsequently fail to develop fully into social animals. Comparative psychologist John Paul Scott dubbed life’s key developmental and socialization stages “critical periods” to emphasize how essential they are for many animal species.

Although people are more complex than canines socially and behaviorally, both dogs and humans are fashioned by interactions at a young age. More specifically, children and young adults undergo socialization processes for which elements of family, fraternity, and fidelity play key roles. In my life, two formative events influenced my adult conception of justice and injustice. The first incident turned the homespun idea of “family” on its head, warping certain expectations about honest interactions. The second experience took place at college in the Midwest upon discovering how some time-honored social institutions advocating brotherhood and fidelity actually operate through duplicity.

I can still hear her words. “If someone is a member of your family, you must love them.”

Each time my mother repeated the statement when I was a youngster, emphasizing “must” as she always did, I thought there had to be something wrong with me. I never believed the statement as a child and came to reject it more vigorously as time went on, thinking any argument merely repeating a single note is not much of an argument. What kind of love must I feel? Mom was apparently championing some ideal about family affection, or did she mean dutiful acceptance perhaps more common during mid-twentieth-century America when wives acceded to the whims of husbands, and children were often expected to speak only when spoken to, and be seen but not heard?

Both my parents worked diligently to save the money to put me and my older brother through college. Their convictions about the merits of education found early expression with mandatory piano lessons when we were kids. Though many children find learning the piano grueling or even punishing, I took to the keyboard and had an epiphany on first hearing the opening chords of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto #1 on a stereo recording. The piece touched something in me. After a few years of effort, I could imitate what sounded like Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninoff, at least in the privacy of my own house.

Would I advance to a dazzling career as a performer? Hardly. The truth is that I could fool a naïve ear by striking all the right piano keys, but I would never match the interpretive genius of someone like Van Cliburn. Lots of people can hit all the correct notes pivotal to an undertaking, but few bring something extra to the experience of art. Something else blocked my ascendance to a music-performance platform. I developed a form of teenage angst commonly known as stage fright, or in contemporary terms, performance anxiety.

For those who never experience the phenomenon, imagine your heart suddenly pounding, mouth going dry and body shaking, a shortness of breath so urgent that gasping for air becomes painful as sweat trickles head to toe. In short, imagine feeling as though you are going to die at unpredictable intervals for days and nights in advance of a performance, and you have the beginnings of insight into the psychological experience of performance anxiety.

Was it unreasonable of my parents to expect a little payback after years of investing in piano lessons? Surely not. However, what they wanted me to do during my 15th year could not have been more personally terrifying. I was being asked to speak publicly about music and then play the piano before an audience. These were precisely the two activities that elicited the worst kind of panic. But I had a choice. I could accept the request and suffer weeks of misery, or refuse to play. I refused, unable to explain why thanks to irrational adolescent embarrassment.

The reaction of both my parents to the refusal was to withdraw affection. Among the elements that had previously shaped my concept of family were openness and honesty. Members of a family did things for one another willingly and honored one another’s requests. Suddenly, I could not do what my parents expected. In their eyes, a refusal amounted to rejection of the very idea of family, and I was judged wanting in obedience, therefore no longer a member of the family. I recall watching my mother and father drive away in the car on some long-planned trip intended for the entire family, with me left standing in the driveway.

The experience seems hardly worth mentioning in a world where abandonment, rampant poverty, and child abuse are not uncommon. Considering the incident from my parent’s viewpoint, I behaved as a self-indulgent, self-centered kid. Though the memory of emotional pain is real enough, I can better appreciate their response now, knowing they had little insight into my deep-seated adolescent terror of admitting to being terrified.

Things did not always run smoothly with other members of my family either. From the time I could first remember, it was obvious that both of my paternal grandparents did not approve of my mother. Their dislike sometimes erupted as vocalized hatred, and I never understood why until I ask my mom to explain the matter after she was well into her ninth decade of life.

“Oh, dear,” she began, “your father could never bear having such things discussed in public.”

My father? What did he have to do with it? And bear what? If the mystery of family dynamics had remained a closeted topic for decades because of my father’s sensibilities, exactly what had been so uncomfortable?

My mother explained how she had been briefly involved with a young man before my dad, leading to an unconsummated marriage lasting only a couple of days before annulment. When I asked my mother if the man had been gay, as I am, she blinked and smiled. However, in the minds of my old-world grandparents, the simple fact of a broken marriage contract constituted a violation of religious and moral principles. Mom was a fallen woman in their eyes, a “dirty whore” as my grandad once put it during a Sunday afternoon drive in the country, regardless of any other notions of fairness and justice. So much for love of family.

Another incident that shaped my view of the world called into question the concept of justice on a broader, social scale. I attended university during the Lyndon Johnson administration, when societal controversies involving racial injustice, the immorality of war, poverty, environmental protection, and civil rights often dominated the news and conversations around the dinner table. At my liberal arts school — one of 21 Wesleyan campuses across the U.S. — more than 90% of freshman students joined a fraternity or sorority. Though historically affiliated with the United Methodist Church, my Midwestern university did not preach Methodist dogma or that of any other religion. Still, consumption of alcohol was forbidden on campus, dormitories were segregated by sex, and at least one of the principles in John Wesley’s 18th-century Manifesto — specifically #6: Promote tolerance — was celebrated. I can’t recall during five years as an undergraduate, witnessing a single instance of alcohol or drug use on campus.

If nearly every freshman student joined a fraternity or sorority back during that comparatively innocent era, what made Greek life so compelling? For starters, university policy required participation at two get-acquainted “smokers” each day at meal times during the seven days of Greek Week held every year before autumn classes began. The alternative to pledging was social isolation in an institutional-looking dormitory. The fraternity house I pledged along with 27 other freshmen that year was appealing in aspects ranging from architecture to emotional comfort. Picture eight massive, Ionic columns forming a portico leading to the entrance of an Edwardian mansion. Envision eighty-some young men living their young lives together with all the exuberance relative wealth, health, intelligence, and good fortune can bring. Greek life was as attractive back then as its alternative was unattractive. Not to pledge a sorority or fraternity was to invite social isolation and the stigma of nerd-dom.

The incident that ruined my naïve concept of Greek brotherhood took place during sophomore year. A young man who had remained independent as a freshman was invited to dinner at our fraternity house, once, twice, and again. Everyone liked him, and he was invited to pledge, except that — hold everything, bro — one or more of my frat brothers had the idea of seeking approval from our home chapter. Why take this unusual measure? When the governing board got wind of the intention to pledge a student with darker skin pigmentation than our own, all bets were off. Such action, the fraternity officers explained, was a violation of our national charter. In effect, my fraternity, fond of preaching brotherhood and humanity, practiced racial discrimination simply because the national charter had stated sometime back in history it must be so.

Must one honor one’s parents and meet their commands no matter what? Must one follow the dictates of a prejudicial board of governors? Must one accede to institutional policies of discrimination and exclusion, or to national policies centered on exploitation and war for that matter? The decades of the second half of the Twentieth Century were punctuated with frequent and stunning reversals in traditional viewpoints, sometimes leading to revolutionary advancements of opinion. In politics, the photo of a burning child fleeing napalm led many to question the motives of leaders in espousing the morality of military engagement. In geology, the gold-standard concept of gradualism — the idea that change occurs slowly everywhere — was exploded by discoveries about asteroid impacts and plate tectonics. Neuroscience began to revolutionize our understanding of brain function, and researchers in genetics were starting to untangle the genetic codes of simple organisms, eventually including humans. Advances in civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights all seemed to alter long-established beliefs about the world and how it ought to function. Suddenly Americans lived in a place where post-traumatic stress was acknowledged as an ailment that could ruin the lives of war veterans and their families, and black holes could rend the fabric of space.

Back down on earth and on a personal level, what had I learned about love and acceptance? Beyond cinematic fabrications about romantic love, and starting at a tender age, each of us is likely to encounter and be tested against societal precepts regarding aspects of real love: love of parents, siblings, and other relatives; love of a broader circle of brothers and sisters with whom we may live, work, and function; and love of the nation in which we are born and eventually die. Family, fraternity, fidelity: what do they eventually mean to each of us? In my case, I discovered love of family was not so much about some romantic notion of affection or positive feelings for those individuals with whom I shared bloodlines, but, rather, it derived from obedience of a particular kind centered on loyalty plus respect for authority. An absence of obedience elicited negative judgment and rejection.

I learned that fraternal love and the larger concept of human brotherhood sometimes rests on a foundation of bigotry, and sometimes that base is literally engraved in stone — as it is in many Civil War monuments — and other times written in a book of regulations or unwritten as an implicit code. Here again, the language of brotherly love developed by many during a critical life period is actually expressed as blind loyalty and adherence to the letter of authority.

I learned that romantic love was not only desirable, but venerated as almost divine in literature, the cinema, churches, and virtually everywhere else, unless an object of affection had matching genitalia. Then all bets were off.

I learned that love of country, so often presumed to celebrate the lofty ideals of democracy and freedom, in fact hinged too often on knee-jerk loyalty and submission to authority while men holding the reins of power championed bombing their adversaries “back into the Stone Age,” as General Curtis E. LeMay said about the North Vietnamese in 1965.

In the end, there is love in the world, real love. There is loyalty, there is authority, and there is truth. As adults, each of us is influenced by what we’ve experienced at a formative age, and some of us grew up to equate love with loyalty and respect for authority. Some of us stopped thinking about connections right there, though a second thought is in order.

Family, fraternity, fidelity. What did I learn about them during life’s critical periods? The answer is a few lessons that will hardly garner accolades. I learned that love of family can sometimes be reduced to obedience to parents. I learned that brotherly love sometimes amounts to obedience to authority as codified in written or implicit bylaws. I learned how love of country can sometimes be reduced to paying taxes, acceding to laws, and blindly supporting authorities and their adherents — often personified as “our leaders” and “our troops” — engaged in international exploitation, and that not to agree with widely held political assumptions is to invite being branded a coward, traitor, or worse.

After they deleted me for a time as their son for disobeying a directive, perhaps I loved my parents a little less, though I forgave them long ago for being merely fallible. For discriminating against another human being and treating a potential brother as something less than human, I came to respect my fraternity bros much less as members of a larger organization in which at least some should have known better and spoken out. Yet I did not speak out at the time. Finally, and though it is unpopular to say the words out loud, the intentional blindness so evident at personal and organizational levels is too often replicated at the national level. For exploiting the weak to gain an advantage, usually monetary, I honor my country far less today than when I was a kid mouthing the Pledge of Allegiance, knowing millions of adult citizens like myself are accountable while profiting these days and remaining compliant.

None of us is perfect, but perhaps the critical period for human decency — let alone socialization or love — spans not weeks or months, as John Paul Scott stated in his psychology of socialization, but a lifetime. If so, then we can do better.

Robert D. Kirvel

Robert D. Kirvel, a Ph.D. in neuropsychology, has works appearing in 45 literary journals or anthologies and is co-author of numerous articles in refereed science and technology journals. Awards include the 2020 Steel Toe Books Prize in Prose, Chautauqua Editor’s Prize for nonfiction, Fulton Prize for the Short Story, ArtPrize for creative nonfiction, and two Pushcart Prize nominations. The author has published in the U.S, Canada, U.K, Ireland, New Zealand, and Germany. Most of his literary fiction and creative nonfiction articles are linked at @Rkirvel. His novel, Shooting the Wire, was published in late 2019 by Eyewear Publishing, Ltd, London. Steel Toe Books will publish his new collection of essays, iWater and Other Convictions, in the autumn of 2021.

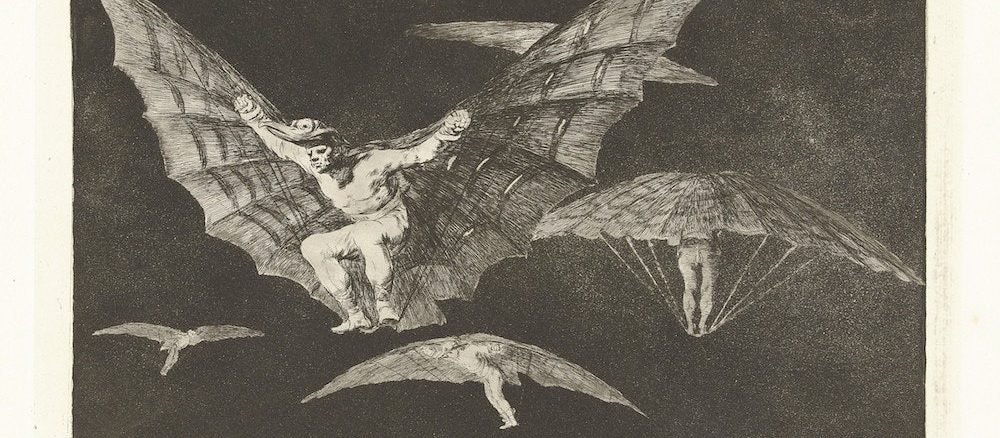

Featured image: Artwork by Francisco Goya on Public Domain Review.