- The body’s constant is a state of impeding change.

- Change is the inevitable state of bodies, be they human, animal, cultural, historical, political or artistic. History fills itself gleefully with stories in which a hero defeats the ominous threat of change. An invading army is routed; a youth-granting spring discovered; an absent love is returned. These are cultural, historical and social examinations of change.

- In each example change represents an outcome that accomplishes the impossible of freezing cultural time like an ice sculpture. We see the invaders turned from their sack of the city; the debilitating and eventually fatal process of aging is slowed or ceased; the eternal contract of marriage provides stability and a model for being a body that does not change. Aristotle, who both feared and adored change, worries about the subject frequently.

- I have to imagine that in the evenings, Aristotle goes down to the docks and tricks the gulls into helping him categorize all the fish in the ocean by their virtue.

- Because bodies are always subject to the threat of change, they are objects which contain further objects—they are like an expanding stamp collection or a snake molting skin but then wearing it again as a coat. This explains Aristotle’s adoration for change without actually changing anything. One could call this philosophy and wash their hands.

- Change makes the efforts of categorization difficult. For example, I am a woman. I also used to be a boy. Or, more accurately my objects that contain smaller, different objects are a multitude of contradictory examples which were once cultural positions of opposites. My aggregate can only be counted singularly. This is a complication.

- Aristotle believes that too much of something is bad, sometimes. This is didactically a simple formulation: too much wine causes the sickness of drunkenness; too much water is a flood; too much food engenders the rot of disease.

- When I consider the idea of change, I think about how often I quantify pleasure and worry about excess.

- Aristotle discusses pleasure in Nicomachean Ethics as if it were an impending change to be categorized. This appears nearly an afterthought.

- For Aristotle, not all pleasures are the same nor are they even all pleasures.

- Aristotle claims pains inflicted in the service of medically advancing wellness is, despite being not-pleasurable, a pleasure. This is like how a hole in the ground is a hole in the ground until the architect sinks foundation or fills a grave.

- It follows that pain is not a craft until it creates a product, i.e., a bruise or deep scrape.

- The first time I was given a description of another trans woman’s recovery from gender confirmation surgery she described waking after as if someone stuffed a hedgehog inside my crotch.

- I desperately want to believe that Aristotle, who desired to make the night sky into a vast public building, would call this “good”.

- “Good” in this Aristotelian context is a dream that concerns itself with the act of virtuous architectural creation. Pleasures which are good, to Aristotle, are those produced by the natural human state of harmony. I.e., how study is pleasurable, or the way my own gender transition has allowed me to look others in the eye when we speak.

- Pleasure is a boat held aloft by an avoidance of pain. Pleasure is a boat made of understanding that pains exist coeval with pleasures. This is a craft like vinification or the employment of rhetorical speech in the marketplace. This is an unmeasurable quantification of a philosophic quality.

- When Aristotle suggests that others believe that sexual intercourse is an act of silencing the mind, he is not convinced but I know exactly how that feels. Because her fingers are electric they gag me. I cannot speak. I know this is not what Aristotle had in mind when he wrote of sex. This begs the question of if silence is the result of the body’s pheromonic artistry.

- I have always desired for pain to be pleasurable and this is a transformational desire because pain is not pleasure unless one exists within a state of natural equilibrium.

- One may look no further than Sade’s proclamation that, “It is always by way of pain one arrives at pleasure” to see this concept persists as a strange disconnected corollary to Aristotle’s taxonomy of pleasure. This exists within this same tradition of mapping bodies within boundaries that inform themselves through performance of pleasures and/or pains.

- She beats me until my mind is empty. She admires the resulting bruises like counting the petals of a forget-me-not that always ends with “she loves me”.

- My body understands change far better than it understands this shifting collection of disparate phenomena we might call a “history of the body”. Every moment is a new history for the body.

- This is difficult for Aristotle, whose purpose is to demonstrate that the architecture of virtue concerns the adoption of goodness as a claimed natural-state. I.e., that health and right action produce contextually pleasant experiences.

- When the sting of an impacting instrument strikes my skin I am electric with the desire for it to craft a lasting mark in black, yellow and rich purple. My partner smiles and hits me again, her eyes like two saucers she desperately desires for me to fill my own desires with her gaze.

- This is an act of crafting. When she leaves bruises on my skin I think about sex and how the mind is rendered empty. I am unable to speak.

- We quantify ourselves as if we were students conducting research. She asks me to provide her with a numeral between 1 and 10 representing a translated relationship between bruising, pain and pleasure. I find a way to lie because I desperately want the application of these bruises to prove a kind of transformative good.

- If being like Aristotle is the goal (Aristotle would agree with this endpoint), then I am like a student tenderly engaged with the excess of study. Every short breath is poem. And I bloom like a sestina employing the word vespertine. That is to say, with great difficulty and inevitably.

- This is like a spigot that provides potable water to the weary traveler. It opens and closes only when there is the pain of thirst which is a transformative pain. Thirst is recursive. It leads to the satisfaction and elimination of thirst. Aristotle would call access to food, water and shelter a “natural state” as he would also call painlessness a “natural state”.

- What is the taxonomy of my desire for health? Can it be sorted into boxes like this body or is it a discrete part of this body able to be separated and filtered into a pleasure?

- I worry that my categorization of pain is too influenced by my categorization of men. Both as things to be avoided because they are unpleasant.

- She beats me like Aristotle crafts the good and my mind is silent.

- Eventually I understood that I am a crafted thing. My body is an artifice that was sculpted from unease. When I say that I used to be a boy this is true just like saying that I used to be a creature made of painful things is also true. I was, as Aristotle would carefully note, unhealthy.

- My transness exists as a discourse of medical intervention which is indistinguishable from Aristotle’s taxonomy of pleasure as arising properly within a state of health. Masochism is merely the process in which I transform my excess into good health.

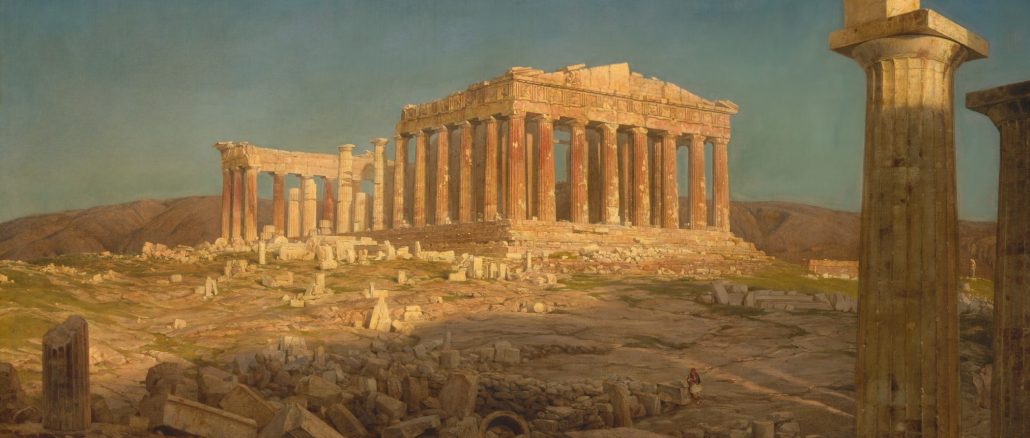

- I engage myself in the taxometry of pain and determine craftship like an architect surveying this body for correction. So when impact against skin leaves a growing bruise I become quiet and admire myself like an ancient Doric column. This body is de facto and constructed with the correcting of objects.

AUTHOR

Danielle Rose lives in Massachusetts and used to be a boy. Her work can be found or is forthcoming in The Shallow Ends, Sundog Lit, Pidgeonholes, Barren Magazine & Glass Poetry.

daniellerosepoet.wixsite.com/home

Twitter: @kittiesnstars

Featured image: Frederic Edwin Church, “The Parthenon,” oil on canvas, 1871. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.