I stand hipshot on the sidewalk, shifting from one foot to the other, left foot on the stoop, then right, half-listening to my mother and Mrs. Aserine catch up—who died, gave birth, divorced, moved, miraculously recovered from cancer—that would be Dorothy Sullivan, my 2nd cousin once removed. Dorothy lived across the street from us, one of a large family of Sullivans, but I don’t remember ever meeting her.

“It’s been more than 40 years,” my mother replies to Mrs. Aserine, who asked how long ago we moved to the island. “I cried every day the first year we were out there.”

As I shift my feet, women come and go via the alley and from the back door of my aunt’s old house—the house where my father grew up—every two or three minutes.

At first I can’t imagine what they’re doing—coming and going so quickly, in such short intervals, but gradually I figure out that they’re carrying wigs, some in round suitcases that remind me of 1960s luggage, some in shopping bags, and finally, one perched on a Styrofoam head. When I break into my mother’s conversation and ask Mrs. Aserine, she tells me that the woman living in my dad’s old house is a Hasidic Jew—she washes and styles wigs for other Hasidic women in the neighborhood.

It’s Thursday afternoon, and these 21st-century Jewish women are fairly affluent, if their clothes and cars are any indication—they wear lovely, conservative suits, long-sleeved silk blouses, skirts down past the knee, and drive shiny new Camrys and Accords and Acuras. And I watch them, these women, walking the same path as the down-and-out men who used to come to the back door of my grandmother’s kitchen—the same back door—for sandwiches during the Depression. The women walk quickly up and down the same alley where my cousins, Dave and Steve, and their friend, Robbie Russo, set off a rocket that showered sparks onto the roof; toward the same tiny back yard where my cousins Joni and Jaci played circus after a trip to Ringling Brothers, and where Joni, in an attempt to be the acrobat hanging by her teeth from a rope, climbed up on the back stoop, bit down hard on the old pulley clothesline and told Jaci, through clenched teeth, “Wheel me out!” Jaci wheeled her out, off the stoop and into the yard, so she was hanging over the grass, a few feet off the ground. Joni hung on for all she was worth, at least until her front baby teeth ripped out.

***

It’s on a sunny summer day some 40 years later that I have dragged my mother to Brooklyn. Our first stop was 12th Avenue and 65th Street, to see Angel Guardian—the place from which I was adopted, the place where the first five months of my history are recorded in files that are sealed, secret, hidden, never-to-be-revealed—nothing more than bits and pieces of non-identifying information squeaking out between the covers, never enough to produce even the most basic narrative, the simplest story—nothing more than “Your mother gave you up to give you a better life.”

The building is old and beautiful and I am surprised by this, surprised, really, by its existence at all—so much is the stuff of story. Inside, though, it is institutional, dim, and now called MercyFirst, a new division of Catholic Charities, no longer the Angel Guardian Home. We enter through a temporary structure, a side door, the front door no longer used. We introduce ourselves to the receptionist, say we are here for a tour, to meet someone called Helen, and moments later, Helen appears.

I look her over, and wonder what she knows about me, my file, my birth mother, whether she is privy to all the information that I am not. She is older than I am but too young to have been here around the time of my adoption. I imagine her down in a musty basement, wandering through row after row of dusty old wooden file cabinets, looking for 1967. I imagine her reading my file, memorizing the information she is not allowed, by law, to share with me, so she doesn’t let anything slip.

I try to extract stories from her, as she shows us around Angel Guardian. Helen tells me that Angel Guardian was once a home for unwed mothers, and that there was a nursery for the babies waiting to be adopted.

I ask if my birth mother lived there, while she was waiting for me to be born, and Helen says, “I don’t think so.”

I ask if I was in the nursery at any point, and Helen says, “Probably not.”

I ask if my birth mother would have come here, to this building, to arrange the adoption. Helen says, “She might have, but often, birth mothers worked with their parish priests to arrange things.”

I ask logistical questions, whether I came here from the hospital, how I got here, who brought me, whether I was brought here at all, whether I was ever here before the day my parents picked me up, but Helen is unable to answer.

I have about enough information here to do a 3rd grade, hand-written, one-page report, I say to myself, as we walk around the building. And I am disappointed.

I want something concrete to hold on to. I want to know I was somewhere, definitely. I want to stand in a spot that my birth mother stood in 42 years ago. But Helen is not forthcoming with specifics. No matter what questions I ask, and no matter how I vary them, I get nothing from her.

Helen, I think, would make a good subject for interrogators to practice on. I think, as well, that if my father had this job, he’d tell stories. And along the way probably expose all sorts of personal, private, confidential information. People need stories.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion says. And how can I live, when five months of my life are storyless?

I want to stand in just one spot my birth mother stood. I want to absorb the air right there, touch the ground, see what residue she left behind. I want to feel what she felt even for just a second, the way I can see and feel and touch E. 2nd Street, and know things.

***

We’re on a journey, or I am. I want to relive the trip from Angel Guardian to E. 2nd Street that my parents took on the day I was adopted. I want to be in that moment—the adoption moment—the handing over moment—to see if there is anything that moment can tell me. That moment. The last moment I was in any way connected to my birth mother. That moment when we were all in a room, social worker, the nuns of Angel Guardian, me, my parents, my file. The moment, the split second before my life sped away from itself and I was reborn as who I am today, a member of this family, immediate and extended, a package complete with a richly storied history. That moment, if I could get back to it, might yield some clue, some truth, some elusive thing that is now long forgotten—some clue to the identity of that parentless, storyless baby in the moment before she became me.

There’s a moment when you are moving out of a house or an apartment—a split second when it becomes no longer yours. Perhaps you hand over the key and that simple gesture changes everything. Sometimes it happens while you are packing, and you miss it. Wrapping one particular item—this dinner plate, and not the one before it—in bubble wrap and putting it in a box tips the balance and suddenly this is no longer your home.

But for years, and even still, the narrative of the adoption, of E. 2nd Street as home, as the place of the birth of our family, has neatly and quietly subsumed the gaps and silences of Angel Guardian. With just a word or two, a phrase, a sentence at most, five months are told, closed, done, over, negated.

Our adoption story—my favorite bedtime story—goes something like this: years ago my parents met and got married and waited and waited for God to send them a baby. When they got tired of waiting and praying, they decided it was time for some outside help, and they went to the Angel Guardian Home. They drove downtown, in Brooklyn, to pick me up, and after my father told the nuns they would never get me back, we all drove home. And when we came down East 2nd Street, a whole pack of kids—all my cousins who lived there too—came running after the car and surrounded my mother like she was some kind of celebrity, shouting, “Elizabeth’s home!” My birth mother loved me so much that she gave me up to give me a better life. We were meant to be a family; God just took a roundabout way of getting us together. E. 2nd Street becomes where my life starts; it is the womb from whence we all came. And as I grow, I hear stories—my dad’s life on E. 2nd—he was born in the front room of 1133—his friends, his sisters, my cousins growing up there too. It is as storied as Angel Guardian is bereft.

One of my friends adopts a baby and I want to stay “Stop! Slow down! Don’t rush her home with you without taking notes, without remembering every single thing, losing contacts and stories and where-you-come-from. The moment she becomes yours is also the moment she loses someone, something, maybe even her self.”

***

It’s as though I were born in a conference room at Angel Guardian, fully formed, five months old. But as it turns out, Angel Guardian figures as much in my story as the hospital in which most people are born, emerging from their mothers’ womb, living their first seconds in the delivery room. And there is no more evidence of me here, 40 years later, than of a birth in a delivery room 40 years after the fact.

There’s nothing here for me. I was, at best, and only perhaps, a passerby, a transient, in this space, and I sense no residue, no spirits of my ancestors, my birth mother, at Angel Guardian. Angel Guardian, it turns out, was just the conduit. The way home. The transportation. The transfer. Where I changed trains, like when I switch from the local to the express at 96th Street, going downtown from Columbia.

The kind but unforthcoming Helen finishes our tour, leaves us in a chapel my mother has no memory of, but where Helen says all the babies were dedicated to the Blessed Mother. I want to stay, wander the building, touch things, absorb, but it’s not that kind of a place now, so we leave, and on the way out, I take pictures of my mother in the old entrance—carved woodwork, muraled ceiling, marble staircase, statue of the Virgin—she thinks that she and my dad used to come get me, even though that door is now closed off.

And the trip to Angel Guardian proves fruitless—frustrating, and fruitless.

***

I have Mapquested the route from Angel Guardian to E. 2nd, but Mapquest is not a Brooklyn native and my mother says this is not the route we took home, that first time. She’s not sure, but she thinks my dad would have taken 20th Avenue, or maybe Bay Parkway. I call my dad to ask; he’s not sure either. “We might have taken Bay Parkway all the way down toward 86th Street,” he says, “or 20th Avenue. . .I’m not sure. . .I can picture it. . .crossing New Utrecht. But I’m not sure.”

We’re not prepared. We don’t remember. So much is lost. And all of this continues to silence the fact that I am adopted.

***

But just a few minutes later, we arrive on E. 2nd, just like I did, more than 40 years ago.

And just like at Angel Guardian I search for evidence that I’ve been here before—I look at the trunks of trees for small handprints—I learned to walk on these sidewalks—and I look at the concrete for scuff marks, footprints, something.

Just like at the broken-down remains of abbeys in the hills of Scotland, stone has a half-life, and ghosts of voices and stories emanate from it like radio-active waves.

But E. 2nd is not preserved like old churches in Europe, and the only shred of stone, of any material I can find that might have been in these houses, near these houses, is the sidewalk, the concrete floor of the alleyway that nominally separated us from the Montemaranos and MacIntyres.

The front porches are gone; the hedges surrounding our patches of front lawn—the ones Dave and Steve used to leap into from the stoop—gone. There is nothing to grab on to, nothing to listen to, to hear, nothing that may have absorbed our small high voices, the sounds of us growing up, our hesitant footsteps, learning to walk in white Stride Rite baby shoes.

I walk along the street, I look at houses, trees, sidewalks and alleys. I take pictures, and later I examine them carefully, process the negatives with held breath, work with them, print them over and over trying to capture the perfect shot, something the film has yet to reveal to me—that only the perfect exposure, the perfect number of seconds in the chemicals of the dark room—the developer, the fixer, the stop—the exact amount of silver emulsion removed from or left on the light sensitive paper, can show me.

But these are reflections I can’t touch—I can’t climb into and relive—their contents as elusive as memory itself.

E. 2nd Street is a world my father constructed out of his thousands of stories of growing up with his three sisters there, about living there himself as an adult, and about the adventures of my cousins who grew up there too.

When I was adopted, on the day I was adopted, the day I came home from Angel Guardian, my parents lived at 1129 E. 2nd Street, in one-half of a semi-detached house. When I was brought into that one moment, I landed right in the middle of story already being enacted, the third act of a play, like I’d hopped a freight train as it was already moving, as it sped away from that moment, it’s tracks always visible in the distance behind it, and in front of it.

This is the street where the postman arrived with baseball cards and other things meant for 10-year-old boys, addressed to Bill Cone, a.k.a. Ann Cone, my dad’s youngest sister, who was a tomboy. She saved her money and sent away for things boys usually played with, from the back of the Wheaties cereal box and from the “Jack Armstrong, All American Boy” radio show, and had them sent to Bill Cone, just in case the people selling them didn’t approve of girls who played ball.

My father has told the story so many times that I know the next part by heart: I can picture my Aunty Ann, the tomboy, Bill Cone, years later, walking home from the elevated line on McDonald Avenue, from her job in the city, just out of high school, wearing chic suits and hats, high heels, neatly catching a renegade ball from a football game and throwing it back to the kids playing in the street. “She’s the only woman I know who could throw like a man,” my father still says. “And she knew more about sports when she was ten than I did when I was fifteen.”

My Aunty Ann was good friends with our cousin, John Sullivan. One day when he was about ten, he was drawing in the street—he always drew in the street, great big chalk murals—my father says he was very talented—when a car coming down the block hit him, and bounced him about ten feet. The man who hit him wanted to help him, but John jumped up and ran into the house and wouldn’t come out, afraid he was going to get in trouble for drawing in the street. “John Sullivan used to run from one end of the block to the other just over cars, bumpers, trunks, tops, hoods, all the way down the block” my father tells me, “from Avenue J to Bay Parkway.”

And at the end of the street, just across Bay Parkway, is the cemetery, where my dad, his cousin Artie, Eddie Doherty, Johnny Keenen, Ernie Tarriff, Buster Wells and Jack Fopiano, when they were twelve, figured out that if you climbed up on top of the fence, you could break off the pickets by kicking them with your heels. “The fence was cast iron, so it was easy to break,” my dad says. “We were going to use them as spearheads.”

But before they could make spears, the cemetery cop nabbed them all, and dragged them off to the cemetery office, where he threatened to call their fathers and make them pay hundreds of dollars to fix the fence. Hundreds of dollars, during the Depression—they were all terrified. He asked for their names, and they stood in a line and gave them:

“Arthur Currey, sir.”

“Frank Cone, sir.”

“Edward Doherty, sir.”

“Ernest Tarriff, sir.”

“Edwin Wells, sir.”

“John Keenen, sir.”

“John Doe,” Fopiano said, drawing out the syllables.

“Don’t be a wise guy, kid!” the cop narrowed his eyes and growled.

“John L. Fopiano, Jr., sir!”

Years before, when a man came around with a pony to give rides to the kids, it was Ernie Tarriff who got on the pony, yelled “Yahoo!” and slapped the pony’s behind, so that the pony man had to chase him (and the pony) down Bay Parkway.

E. 2nd Street came complete with a haunted house—Ferry’s Mansion, abandoned years before along with a ’28 Pontiac in the garage—and an empty lot. Every year my father and his friends would collect all the old, dried out Christmas trees along the block, haul them off to the lot, stand them up against the adjacent brick house, and set them on fire. “It was a brick house,” my dad says, “so we knew it wouldn’t catch fire. But I guess it got pretty warm inside!” Sometimes, when the weeds got high, they set fire to the lot itself to clear it out. “We always offered to help put the fire out, but the people who owned the lot always said, ‘Are you kidding? You kids probably started it!’”

One year, the Dayhill Road guys, who hung out on McDonald Avenue—rivals of my dad and his friends—got hold of a dead cat and buried it in their own empty lot. My dad and his friends dug it up, and burned it. “We immolated it,” my dad says, and I imagine the Franciscan brothers at St. Rose of Lima teaching the boys the word “immolate,” never expecting them to put it to such good use.

They were, for the most part, good, if mischievous, Catholic boys, and one day, when they were on their way to school, a young Jewish mother left her baby in the carriage outside a store, and the boys baptized him with water from the gutter to save his soul.

These are my bedtime stories; it’s the children of my dad’s cousins, his friends, my first cousins—Joni, Jaci, Dave and Steve—and my second, third and fourth cousins once and twice removed, who run down the street to welcome me home from Angel Guardian; this is the story I joined, became a character in, the moment my dad turned the Pontiac on to E. 2nd Street on way home from Angel Guardian.

But I can no more find the E. 2nd Street of my father’s stories than I can find Mt. Olympus—my young cousins, my father’s pack of 10-year-old friends, my grandparents and my great-grandmother, the gods of my childhood, accessible like Zeus, Apollo, Diana, only in our own mythology.

***

Two years after the Angel Guardian journey, I am back.

I am shooting film for a photography project I have embarked upon, to decipher the mystery of E. 2nd, what makes it mythological, whether it still exists.

As I walk back from the corner, from shooting nearly a role of film of the cemetery fence, I snap away, and start to notice people watching me. I walk by a number of Hasidic women pushing baby carriages, but none of them return my friendly “Hello,” so I cross the street to where two men are standing on the sidewalk, right across from our old house, talking.

I ask, “Do you live here?”

“Yeah,” one of them says.

“Hmmm…” I say, thinking he’s probably too young to remember us. So I say, “You’re probably too young to know about the block, but I used to live here.”

“My family has been in this house for more than a hundred years, ” he says, fast, indignant, defensive. I immediately grin. This bodes well.

“Who are you?” I blurt out, which must seem weird and rude to him, but to me feels like the obvious next question, since the odds are good that I’m now talking to someone I’m related to, or close. But this is Brooklyn, and he answers me with none of the suburban fear of a Long Islander. “John Rocco.”

“No way! Is your dad Sally Rocco?”

“Yeah, Sal,” he says, his eyes narrowing a bit. “Who are you?”

In my rush to explain I stumble all over the place. “I’m Liz . . . my dad’s Frank Cone? . . . he grew up here? . . . in 1133? The Paganelli’s? My cousins? Do you remember them?”

Somewhere in my sea of fragments recognition clears his face. “Yeah, sure.”

And John Rocco is the perfect Brooklynite, E. 2nd Street resident, to meet, as becomes apparent when he launches into 100 stories, all strung together, about him, my cousin John Sullivan walking the length of Ocean Parkway—on his hands—his dad Sally Rocco and his grandfather, Skippy Bauslager. “He only threw out kitchen garbage. The guy had every issue of National Geographic ever printed. I’ve been cleaning out his place in Jersey for three months.” He introduces me to his mother, Eleanor Bauslager Rocco, who remembers how my father washed his car out on the street every single Saturday, and he tells me that his great-grandmother—Clara Bauslager, the one Skippy Bauslager used to tell to shut up when she called him in to dinner—is 92, and still lives with them.

As he talks, I jump in occasionally, naming names, pointing at houses, adding details to stories. He tells me all kinds of things I don’t already know, and some I do, and I realize that as much as I think I know E. 2nd, or about E. 2nd, I don’t know all the facts and details at all. But I do know the atmosphere. I know E. 2nd as a character in my dad’s stories, and that’s a different kind of truth.

This guy knows my same stories, my father’s same stories, and he’s not related to me unless living on E. 2nd counts, which I think it does. And anyway, his dad and my cousin John Sullivan were, perhaps still are, best friends.

***

And it’s all a little disconcerting.

I think, at first, that E. 2nd, our E. 2nd, does exist—maybe just some fragment—in John Rocco, in Eleanor Rocco and Clara Bauslager, who are still living out their lives and telling stories on the sidewalks.

But as I listen to John’s stories, I realize that I’m confusing generations, that I don’t know who belongs where in time, much less in space. Everyone I know on E. 2nd Street is frozen at the age they are in my dad’s stories, and it’s their ghosts—their after-images—I’m looking for when I peer down the alleys and look for traces of us.

As I think, and write, and develop photographs, I realize that John Rocco’s E. 2nd Street is not my E. 2nd Street. His is real—everyday, argue-with-the-neighbors-over-where-his-house-ends-and-theirs-begins, fight-over-parking-spots real. His has traffic and Hasidic women pushing baby carriages and having their wigs washed and styled on Thursdays.

***

But maybe that’s okay; maybe that’s meant to be. Maybe it’s like when the Pevensie kids return from Narnia through the wardrobe that first time.

“And the Professor, who was a very remarkable man, didn’t tell them not to be silly or not to tell lies, but believed the whole story. ‘No,’ he said, ‘I don’t think it will be any good trying to go back through the wardrobe door to get the coats. You won’t get into Narnia again by that route.’”

This is not a loss. Rather, in some perverse way, E. 2nd Street is saved, and we are saved with it, our stories imbricated in its sidewalks, its tree trunks, the foundations of the houses, if not the exteriors, and most of all in stories.

And yet I can’t resolve this conflict—this needing more information, needing to know my life pre-E. 2nd, and the comfort, the story-ness, of E. 2nd. The belonging. The E. 2nd Street stories seem to point, glaringly, to the silences of Angel Guardian. They fulfill me and identify me and construct me, and leave me hanging all at the same time.

I tell my dad all about meeting John Rocco, and Eleanor, and how they want me to bring him back to the old neighborhood. “Just bang on the door anytime!” John and Eleanor have told me. I want him to come with me and point out the spot where each story took place, where everyone lived. But he says that he feels a little sick when he thinks about how much the old neighborhood has changed.

I want to show him the oldest photos, of E. 2nd when he was a kid, and remind him how he and my Uncle Bob changed the front doors of the houses from glass-paned to solid wood; how they changed the windows in the porch to bay windows; how they painted and spruced just like the people who live there now. But change that you make and change that is made without you, after you, is never the same.

E. 2nd Street is telling new stories now, populated with very small boys wearing yarmulkes, riding bicycles with training wheels.

One such boy came out of his house, my dad’s old house, with his tiny bicycle, balancing on the training wheels, and rode up and down the block as my mother talked to Mrs. Aserine on that first visit. When he came near, I asked him a question.

“Do you live in this house?” I said, pointing to 1133.

“Yes,” he said, a bit wary at a stranger talking to him.

“My dad used to live there, and I lived next door when I was a baby. My dad was born right in that room there, in the front, a long, long time ago,” I told him.

He looked at me for a few seconds, his small brow furrowed. And then he pointed downward, and said, “This is my new bike,” and rode off toward Avenue J.

AUTHOR

Elizabeth Cone writes essays and memoir about the power of story and memory, and what happens when you change your own narrative. She teaches writing at Suffolk County Community College on Long Island. Her work is forthcoming or has appeared in RiverSedge and the Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review.

Twitter: @elizabethacone

Instagram: @lizcone

Facebook: @lizcone

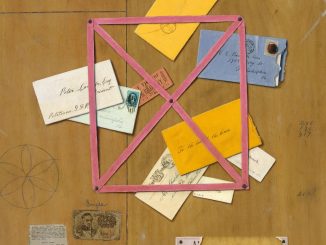

Featured image: Photograph by Maksym Kaharlytskyi on Unsplash.