I wasn’t born in Belmont, but not long after my birth—three months, four—my parents decided, seemingly out of nowhere, that being raised in the city would make us sour and cynical before we even learned to read, so they scooped up our lives (me, my sisters, everything we couldn’t sell in tag sales, and the cat, who was the most put-out of any of us) and set out for picturesque New England suburbs.

If there’s a hell for everyone, I think mine might exist there.

That’s not to say it’s bad for everyone. Belmont’s fine, from a distance, and pretty like you wouldn’t believe. It’s hard to explain if you haven’t been there, haven’t had to curse out the Hallmark Channel cameramen because they’re in your way and you’re just trying to get coffee, Jesus fucking Christ, can you capture Christmas magic in like five seconds and not when I’m already running late. That kind of pretty.

But places like that have a way of testing you. Pop quizzes, the kind you can’t study for, and you’re never quite sure if you’ll pass until you don’t. Belmont doesn’t decide whether you’re part of it or not. It just dangles the opportunity in front of your face, and as soon as you grab for it, it tells you the price.

I tried, at first—god knows I tried—but I guess I always paid attention to the wrong points, tripped up on the easy questions. It was worse for my mother, I think. She’s always liked things to go where they belong, so when her own flesh-and-blood daughter could barely match colors and tripped every time a tennis ball came her way, she must have been shattered. She tried her best to fix it. Private lessons. Hand-picked clothes from the L.L. Bean catalogue. Things that were never going to work if the person underneath wasn’t calibrated right.

So I pushed Belmont away instead. Made friends with a few other kids on the edge and told anyone who would listen how I couldn’t wait to get out. The loneliness still hissed and sputtered behind my ribs sometimes, on nights when the air sent needles through my pores, but I mostly kept it in check. Can’t miss what you don’t care about, right?

Spite. Survival. Call it what you want.

The last test I remember, or maybe the last one that mattered, was the cookout.

Picture me: in a mismatched bikini, picking idly at the half-soggy cornbread from the catering table. If you asked me what else had happened that summer, it’d only come back in flashes—ditching therapy to skip rocks in the man-made pond by the high school or biting my fingernails until the cuticles got infected—but even now, this comes back mint condition, still in the package it came in. I’m barely fifteen, deep in the throes of my high school eating disorder, and basically ready to burn the place down. On my left, Jackson Vail from down the street, on my right, one of the Emilys whose last name I never learned.

Jackson’s been telling Emily about seeing some band I’d only heard in snippets between radio stations for about four minutes. I’m nodding like he’s talking to me and trying to figure out the calories in an individual barbecue chip. And then, from across the table: “Dude, you hear what happened to Charlie?”

Ben Sewell pitches himself into an empty plastic chair and steals a handful of Emily’s pretzels. She flips him off in response, and he tosses her half a nod before turning back to Jackson. “Shipped off to Exeter. His parents think that’ll fix him.”

Even I laugh at that, as much as I’m trying not to care what they’re talking about. We all know how no-consequences kids like Charlie do at boarding school. Jackson snorts. “Yeah, that’s fucking rich.”

“I know!” There’s a smattering of freckles on the side of Ben’s cheek that throws his whole face off-balance. If I look hard enough, I think I can see Scorpio under his eye. I look back at my plate instead. Ben gestures broadly, like he’s trying to capture the essence of Charlie. “He’s a wild man, dude. I’m taking bets—how long till they call his parents?”

“Week one,” Jackson says.

“Day one,” Emily counters, half-grinning. Her hair is flat-ironed within an inch of its life and, by some pretty-girl-magic I haven’t been able to master, still perfectly shiny.

“Before he even gets there.” Jackson talks to Emily not across me, but straight through my left ear. I imagine the words traveling through my head like whispers in a dome. “Five bucks.”

“Ten.”

Jackson, to Ben: “What’d he do?”

Emily, cutting in: “Caught smoking, probably. Or the thing at the park.”

And then the atmosphere shifts a degree. A pause, just long enough that you wouldn’t know to see it unless you grew up watching for them. Ben shoots Emily a look that shouts don’t.

There’s no way I can ask. I don’t speak their language well enough to slip in without disrupting the ecosystem. But Jackson does. “What thing?”

Ben flaps a hand dismissively. “This thing last week. You were still in France.”

Jackson leans forward. He wants a story now: Charlie Harris, hero, adventurer, John McClane of small-town Massachusetts. “Yeah?”

“Yeah, Mel brought some vodka. You should’ve seen it, dude, she was fucking wasted. Passed out in the gazebo at, like, eleven.”

Unexpectedly, Emily whispers to me, “She’s such a lightweight, but she won’t admit it.” When I glance at her, she shoots me a grin, and I try not to look too grateful when I smile back. We were never quite friends, but the year before that cookout, we’d sat next to each other in English. She’d always been decent, or at least more so than most people around there.

I’ve still got half an ear listening to Ben, though, who hasn’t stopped talking. “We were gonna bike down and steal the flags from the yacht club, and she’s fucking gone. Like—” He does a slack-jawed impression, eyes half lidded, slumped against the table. Jackson and Emily are leaning in, and I catch myself doing it too, as the expanse of his world spins out in front of me. “And Charlie’s barely drinking, ‘cause he’s a pussy.”

I don’t think before it’s out of my mouth. “Yeah, what else is new?”

For a second, nobody answers, and I brace myself for the blow. Realistically, I shouldn’t have even known to say that, but I’ve been around long enough to hear the names Charlie gets called when he isn’t around. But Ben doesn’t shut me down. A shadow, almost like approval, crosses his face. “Fuckin’ right.”

Emily’s eyes slide my way. A half-smile plays at the corners of her mouth. The right words to keep their attention are floating somewhere in front of me, and I reach, stumble, graze them just before they could float away. Ben waves a hand, and they dissolve. “Yeah. So Mel’s done for, and Charlie’s a pussy, but he’s hanging around near her for like, five minutes, and then he starts making out with her.”

A beat. Jackson laughs, just barely. “While she was still—”

“Yeah, duh. She was out.” Something about Ben’s grin is older, crueler. He’s buzzing with the weight of the story. I almost expect his freckles to start pinging off of each other like an Atari game. “Austin pulled him off when he started undoing her shorts.”

“That’s horrific.”

And before I can regret saying anything, all eyes are on me. A series of unfiltered expressions flick across Ben’s face. “Huh?”

“That’s, like, fucked up.” I want to sound righteous about it, but it comes out half-stuttered and flippant. My fingers are twisting in the plastic tablecloth. “He tried to rape her.”

“It was just a joke. He wouldn’t have done shit. It’s Charlie.”

His tone hits me between the eyes: a drive-by reminder that I don’t belong in this conversation. Some almost-forgotten feeling, hot and half feral, pulses in my stomach. “That doesn’t make it okay.”

Ben turns to Emily and rolls his eyes. “Back me up. He was kidding.”

Maybe six months before that, I’d sat in class next to Emily and egged her on while she talked about decking a junior for grabbing her ass in the hall. She’d been—at least in my memory, and that’s faulty at best—some kind of avenging angel, a Valkyrie in Adidas. Sounds corny, now, but I was a kid. You want those things to be real.

Now, Emily’s eyes flick to me, and back to Ben. Her answer comes only a fraction of a second late. “It was, like, nothing. Mel was fine. She didn’t even remember it.”

Ben nods with something that isn’t quite approval. “See? He’s just crazy.”

A second, where the barbecue seems to go silent around me. The thing in my stomach bares its teeth. I try to push it down like usual, but it’s getting louder, clawing up through my ribcage, this rabid slobbering lonely desperate creature that wants, and wants, and wants, and for a second my resolve slips, and I—

I don’t know, actually, what I want right then, except that it’s too much. I want Emily on my side. For her to be disgusted with Charlie, and with Ben for laughing. To speak whatever language it is that lets them brush this off. To be ten pounds lighter, five shades blonder, a hundred times better at saying the right thing. To go to the park after sunset and drink shitty vodka with people I have inside jokes with. To hold the secret in the look Ben shot Emily, and every bit of easy belonging that goes with it.

And most of all, maybe, I want what Mel has now. Not the act, but the aftermath of it: a real reason to hate this place that’s not just an inability to be what it wants.

The creature wins.

I dislodge a laugh from somewhere in my throat and cough it out. “Crazy. Yeah.”

But I’m already seeing the conversation move on without me. Emily makes some joke about a regatta last month I didn’t go to. I can feel it happening even before it does, the door to that shimmering world closing just before my fingers reach the handle. Somewhere in my peripheral, Ben pushes himself up from the table. “I’m gonna hit the pool. You coming?”

He isn’t talking to me anymore. Jackson doesn’t even answer, just hops up and follows after him. Emily takes a second longer, cleaning up the plates they left behind, and as she does, I manage to catch her attention. “Hey. That was fucked up, right?”

Six of Emily’s pretzels are left on the table. Before she answers me, she picks up each one individually and drops them onto the plates. “No, yeah. Definitely.”

“You didn’t—”

The plates crease in her hand. “Neither did you.”

I don’t answer, but what we’re not saying hangs between us like wet burlap, and I can’t breathe with the way it’s soaked up everything in the air. We both stare at the pretzels. She picks the salt off one and flicks it away. Finally, she says, “Like, it’s just Charlie. Mel’s never gonna know. You have to—”

Silence, again. I prompt, “Have to?”

“Nothing.” Emily looks at me, finally, and for barely a second the animal behind my eyes sees the animal behind hers, sees and is seen and knows. “Never mind.” She jerks her chin over my shoulder at Jackson and Ben’s retreating forms. “I’ve gotta go.”

If I close my eyes now, I can still see the sweep of her hair as she jogged after them, the arc of an injured bird as it pitches from the sky.

I didn’t go back to the cookout the next year. Or the one after. Neither did Mel. If everything had stayed the same afterwards, I might not have even noticed it, but that year, Belmont stopped testing me. No more chances dangled in front of me like prices in a carnival game. No more bright-and-shiny doors to a world I couldn’t bend to fit into. I wouldn’t have taken them, anyway. Did my best to just keep my head down until I could leave it behind, swallow down whatever feral thing made me stumble like that. Even now, I’m wary—two weeks ago, I drove by the exit to Belmont and caught myself holding my breath until it was in my rearview mirror. Bad luck to breathe in near a graveyard.

Maybe it’s ridiculous, building so much of yourself around somewhere you were always going to leave. But I think that’s what homes are. Just places, and the ways you learn to survive them.

GEORGIA WHITE is currently studying creative writing and psychology at Bryn Mawr College. Her work has previously been accepted by the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center, and, most recently, the Santa Ana River Review.

GEORGIA WHITE is currently studying creative writing and psychology at Bryn Mawr College. Her work has previously been accepted by the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center, and, most recently, the Santa Ana River Review.

Twitter: @allhailgeorgia

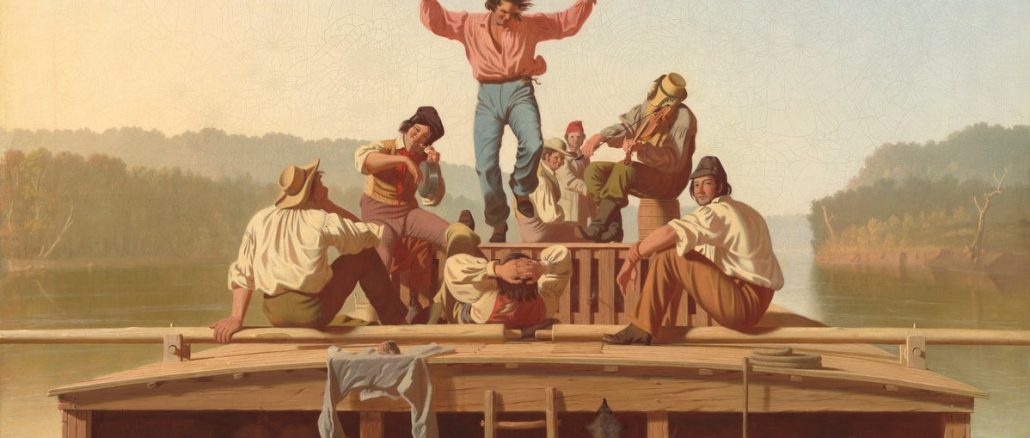

Featured image: George Caleb Bingham, “The Jolly Flatboatmen,” oil on canvas, 1846. The National Gallery of Art.