A strange thing started happening to me recently on Facebook. The “People You May Know” feature started showing me almost exclusively women I had met on Tinder and gone on dates with several years ago. Some of these were women I liked. Some I didn’t. Some of them I had one-night stands with. All of them were faces that I had no expectation of ever seeing again.

In some ways, their presence on my Facebook feed is perfectly reasonable. They are “People I May Know.” They are people I do know to varying degrees, or at least knew once. What feels strange is how they all showed up together. It’s not uncommon for me to encounter some small artifact that reminds me of an ex (passing by an old bar we would frequent, stumbling upon a gift hidden in my closet, hearing a song in a coffeeshop). It’s much rarer that I unexpectedly come face to face with a photo of them, particularly a group of them all at once.

Anyone would feel slightly uneasy about being reminded of old romantic endeavors. In this particular case, though, there’s an extra layer of inquietude in the fact that it is a computational system presenting these old dates to me. At the macro level, I understand how this happened: I saved these women’s numbers in the contacts list on my phone; I have the Facebook app on my phone; the app connects to my contacts list; the suggestions are made.

That they all showed up at the same time seemingly indicates that the algorithm that drives the “People You May Know” feature was perhaps recently tweaked in such a way as to prioritize showing phone contacts. What adds to the uneasy feeling is the idea that a Facebook engineer in Silicon Valley committed a small change in computer code that had very personal results for me. There’s the sense of a lack of control over my own destiny, so to speak, in thinking about how much this small code change can affect my life.

The type of algorithm that drives “People You May Know” is what can more generally be referred to as a recommender system. It recommends people to add on Facebook. Recommender systems are fairly pervasive now as they drive many modern media services. Netflix recommends new movies to watch. Amazon recommends products to buy. Spotify recommends songs to listen to.

Our dependence on the internet now means that these algorithms we only somewhat understand increasingly have broad social implications. In his essay “The Relevance of Algorithms,” Tarleton Gillespie refers to these systems as public relevance algorithms. What makes public relevance algorithms unique, according to Gillespie, is that we now rely on such procedures to deem what is relevant or newsworthy. Furthermore, they are often presented with what he calls “the promise of objectivity.” Because they are performed by cold, calculating machines, we presume that the selection of relevant things—movies, songs, products, news, search results—is done without bias. But these algorithms are designed with certain outcomes in mind, and they may be altered over time in accordance with achieving those outcomes.

In some cases, the results of these algorithms may be fairly benign. For many people, it may be a reasonable assumption that you want to add people on Facebook if you have their phone number and aren’t already Facebook friends. Seeing a collection of old Tinder dates all together is a bizarre experience, but ultimately not too troubling. Still, others have argued that many popular algorithmic systems are fundamentally changing how people behave, which can have important cultural implications.

The internet activist Eli Pariser coined the term “filter bubble” to describe how filtering algorithms limit exposure to new ideas. If Amazon learns, for example, that you like crime novels, it will continue to recommend you new crime novels to read. But might you not be a more interesting and well-rounded person if you read other types of novels? And doesn’t this recommendation process take away the magic from a moment like wandering into a bookstore and choosing something at random, something that may or may not be something you would normally read, but that you end up loving? In the same way, had I encountered some small token in the world that reminded me of a date I went on years ago, it might feel somewhat charming. But a computer simply reading my contacts list and showing me someone I went out with once doesn’t feel charming at all. It feels too precalculated to find any sweetness in it. In other words, I think it’s fair to summarize Pariser by saying that the problem with recommendation systems is a lack of serendipity.

***

It may be fascination with the prosaic details of another person that is fundamental to the idea of love. I was immediately fascinated by Natalie: the way she cleaned the mud off her boots with diner napkins right after sitting down, the way she couldn’t quite seem to sit still in her chair, even the particular way she ate her egg sandwich (not from top to bottom, but around the periphery to its core). It seems silly to say this now so far removed from first sitting across from her in that small diner in Humboldt Park. How could eating an egg sandwich at all be fascinating? I don’t know that I could explain it now.

There was a certain enchantment surrounding the whole morning. Our first date was unlike any other first Tinder date I’d been on. We both happened to be up at the crack of dawn and for some reason had texted each other. We met on a dock in the park early in the morning and sat in the rain, talking for hours, until she remembered she knew a place with a great egg sandwich within walking distance. The details were peculiar and novel, but the details matter less than the overall feeling associated with the morning. Our meeting felt like something special. It felt like a big moment.

There is a tension between a relationship’s routines and its big moments. We live our relationships through the former, but we tend to conceptualize of them in the latter. The day-to-day experience of love is all its little details. For example, Natalie’s nighttime ritual involved those small, plastic flossers. After brushing her teeth, she wouldn’t floss all at once, but she’d carry one around the apartment with her in her teeth while she cleaned up and got ready for bed, her hair in a bun, pausing occasionally to wedge it between her teeth. She’d chat with me, using the flosser to punctuate her sentences, taking it in her fingertips to make a point quickly and then putting it back in her mouth, like a smoker would with a cigarette.

I had my own routines. In the morning, while she slept in, I would slice an apple to eat with two scoops of peanut butter. I would always take one of the slices and cut it into even smaller pieces to give her dog, Iggy, a small, black, adorable mutt. Iggy would sit there next to me while I sat on a stool in the kitchen and I would throw her pieces of apple while I ate before Natalie got up and gave her a bowl of dog food.

But when thinking about a relationship, the everyday routines are discarded instead for big moments. After all, they make for better stories. The wiping of mud off her boots is a small detail, but it fits in nicely with the story of two people being so interested in each other that they would sit in the rain, walk through a muddy park to keep talking over an egg sandwich. How she used flossers speaks little to something fundamental about our relationship, except that over time I came to treasure these peculiarities as I came to live inside them.

Big moments are also easier to remember. While I could fill volumes with the mundane details of my life with Natalie, there are certainly volumes more that have since faded from my memory. But big moments never fade: the time we first met; our first kiss, at The Green Mill in Uptown, the two of us pressed into a small booth; our first trip together, to Michigan, we stayed at a bed and breakfast, swam in the lake during the day then bought an assortment of groceries and ate on the deck of the place in the evening; on the front porch of her apartment building, when I told her I loved her for the first time, and she looked at me and said she wasn’t ready to say it back to me. The trouble with big moments is that it’s not always clear when they’re happening, that they are only obviously so big in retrospect. Maybe saying “I love you” is always a big moment. It seems even bigger now with the benefit of knowing that “I love you, too” was never going to come.

Big moments are how we make sense of our relationships. It is for this reason that we at times try to construct big moments out of small details, even when there’s nothing there. Natalie made two Spotify playlists for me during our relationship: “matt [downbeat]” and “matt [upbeat]” (each with its respective general tempo). Whenever she found a song she thought I’d like, she’d add it there. On days where she seemed more distant, or our relationship somehow felt less solid, I’d listen to those playlists, scrutinize their lyrics, hoping there was some secret message encoded in them that would give me an answer to my dilemma, as if they were saying something she herself wasn’t saying to me. They weren’t, of course. It was just some song she liked to sing in the shower. It was just a small detail extracted from the routine of her life. But I wanted it to be something more.

This is the tension between the everyday routines and the big moments: though we live relationships through routines, we conceive of them as stories made up of big moments in which we are characters following some meaningful narrative arc. I cannot tell the story of Natalie without the fateful big moment in which I declared my love and she did not reciprocate. But our relationship was so much more than a collection of big moments. It was our routines we developed as we gradually weaved our lives together. It was sitting on her couch with Iggy watching Chicago Med on Thursday nights. It was listening to NPR together while I drove her to work some mornings. It was her haphazardly flossing her teeth while telling me about her day. A relationship is so much more than its big moments. It is every routine, every small detail.

***

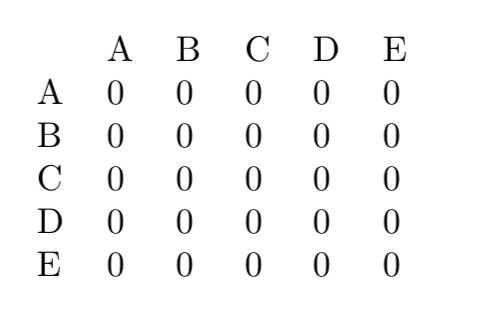

Imagine a universe where only 5 bands exist. They are The Avett Brothers (A), Built to Spill (B), Cayucas (C), The Decemberists (D), and Elliott Smith (E). You could represent this universe as a matrix, where each band represents one row and one column in the matrix. At the beginning of time, you set all values to 0:

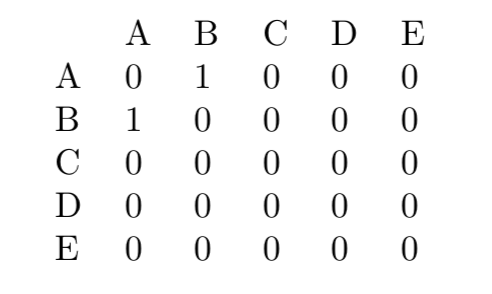

These bands exist on something like Spotify. As people start creating playlists and putting songs together, we can represent this in the matrix. Every time a pair of bands co-occur on a playlist, for example, we could increment the value of that cell by 1. So if the first person in our fictional 5-band universe made a playlist that contained only The Avett Brothers and Built to Spill, our matrix would look like this:

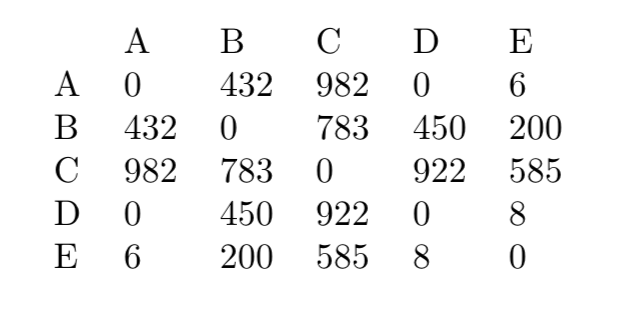

A band now is represented by a vector, or a list of numbers. In our universe, we are less concerned about thinking about The Avett Brothers as an americana band from Mount Pleasant, North Carolina, and instead just think of them as the vector {0, 432, 982, 0, 6}.

Reduction to integers allows us to perform some mathematics. When songs are not collections of instruments and lyrics, but instead just a list of numbers, we can start asking questions not like, are these songs about the same thing but instead like, how far away are these two songs in space? Forgetting all the mathematical detail, you can imagine looking at several points on a 2-dimensional plane and thinking about them in terms of how far away they are from each other. The same principle applies now to our 5 songs. This is very useful for recommender systems.

Imagine we know someone likes the Avett Brothers. We could recommend that they listen to Cayucas, which is the band they most frequently appear on playlists with. Or, instead, we could calculate the distance between the Avett Brothers and each of our 4 other bands based on their values in the matrix and recommend the band they are closest to. It turns out this is The Decemberists, despite them never appearing together on a playlist. This is somewhat intuitive if you look back at our song matrix. While these 2 bands never appeared together, they appear with the other 3 bands about the same amount of times.

In other words, in this fictional Spotify universe, there are Avett Brothers fans and there are Decemberists fans, and they somehow managed to never cross paths. Nevertheless, they seem to have remarkably similar taste. The fact that they ought to listen to each other seems inevitable. Perhaps, given enough time, they would find each other. Otherwise, we could rely on “the wisdom of the crowd.” Each individual creating a playlist performs a small action. But these actions, taken in aggregate and then subjected to some simple mathematics, can introduce these two groups of people who seemed destined for each other.

***

In the weeks immediately following our breakup, I tried to scrub every detail that reminded me of Natalie. I changed my routes to avoid passing by places that reminded me of her. I moved any gifts she had ever given me into my closet and out of sight. I stopped watching Chicago Med on Thursday nights.

Social media has made this purging process more difficult, or at least more involved. In addition to everything else, I had to unfriend her on Facebook, remove her from Snapchat, unfollow her on Instagram, unfollow the novelty account she had for Iggy on Instagram. When scrolling by an especially good dog video on Facebook, I instinctively clicked to comment and started typing her name to tag her as I was so used to doing. It seemed like we had as many online routines as we had offline ones.

There was an oversight in my process, however: one night, upon opening Spotify and looking over my playlists, I noticed something strange. Two playlists had just slightly different names: “[downbeat]” and “[upbeat].” It was the two playlists Natalie had made for me. She’d taken out my name. I was being purged as well. While I couldn’t blame her—I was doing the same thing—how terribly unsettling to get a firsthand look at someone trying to forget you.

I had never stopped listening to the playlists after the breakup. For all my desire to remove traces of her, I could never bring myself to get rid of them. Perhaps I was still searching for some meaning in them, scouring their details to make sense of what had happened, as if in the middle of a song I’d have some epiphany: “Aha! If only I had done this differently, then she would have loved me.” Our story would make sense, the arc of our big moments a tragic, but at least understandable narrative. Whatever it was, I’d found some comfort in these songs. But I couldn’t anymore. Without my name, they didn’t really feel like my songs.

Instead, I found solace in creating new playlists for myself. It seems so trivial a thing to do, but after breakups, we are desperate to rediscover our ability to be someone without this other person. We are our routines, after all, aren’t we? And what were my routines now? I still woke up, sliced an apple, got two scoops of peanut butter. But it felt less whole without the extra step of cutting up the final slice for Iggy. Everything I did on my own now was characterized in terms of lack. So, trivial as it may seem, making new playlists felt like taking control, like proactively finding new things rather than focusing on things I had lost.

Spotify makes it easy to discover new music. You can see what is trending. If you like an artist, you can find similar artists. If you like a specific song, you can go to that song’s “radio station” and listen to similar songs. As you begin to collect several songs together and create a playlist, you can ask Spotify for recommendations on other songs to add. I did this often.

One day, while driving and listening to a Spotify radio station, I realized that the last several songs that had come up were all breakup songs. They were all sad songs, with lyrics fairly explicitly about the end of relationships. Spotify’s algorithmic curation seemed decidedly apropos.

This was no coincidence. It is worth pointing out that, at least to the best of my knowledge, Spotify’s algorithm has no concept of sentiment. It does not know what a breakup song is, or if a song is “sad.” What Spotify does have is what is commonly called “user-generated content.” It has millions of playlists created by its users. It has the ability to create matrices like the one in our 5-band universe, but much, much larger.

I gravitated toward breakup songs at this time, which I suspect is not an unusual coping mechanism. In fact, I am quite certain it is not unusual, because given the small set of data Spotify had about my musical taste at this time, it started recommending me almost exclusively other breakup songs. It did so based on the user-generated content that it had. In other words, the songs I tended to listen to during this time often co-occurred with other sad, breakup-y songs. This is likely because, in the same way I was currently doing, many Spotify users before me had created their own breakup playlists full of sad songs. Spotify might not know what a breakup song is, but it does know that there is this group of songs people tend to play together. In our fictional Spotify universe, Avett Brothers fans and Decemberists fans seemed destined to eventually meet. So too was I destined for these collections of songs.

Breakups, like the act of love itself, are at once deeply personal and totally universal. No one knows exactly what your love feels like, but almost everyone knows what it feels like to be in love. Similarly, breakups feel isolating. You feel remarkably alone. And yet, you feel alone in the same way almost every other human being has at some point.

I was alone in my car that day I realized Spotify was playing me breakup songs. At the same time, that Spotify knew to recommend those songs connected me to the millions of people who had created playlists before me. Somehow, I was contributing to the recommendations some other person might hear after me when they are creating a similar playlist. I was alone, but I was alone with the traces of countless others who had gone through the same thing I was going through now.

***

What is serendipity? The 18th century intellectual Horace Walpole coined the term in a letter. The word is derived from the title of a fairytale, “The Three Princes of Serendip,” in which Walpole noted “As their highnesses traveled, they were always making discoveries, by accident and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of.” We may often think of serendipity as a “happy accident,” which it is. But importantly, as the quote points to, it happens not just when we weren’t looking for it, but when we were looking for something else altogether.

Don’t recommender systems contradict this idea? How can a person make a discovery of something that they were not in quest of if they weren’t in quest at all? Someone may stumble into something magical unexpectedly when perusing a bookstore. If Amazon shows you what you want on their front page, where is there to stumble?

But maybe this view is too simplistic. In thinking about the effects of any given technology, it may be useful to ask ourselves: how would we behave if that technology never existed? It is a romantic notion—the idea of unexpectedly finding a book that changes your life. But how many people actually behave this way? Even without Amazon, didn’t crime novel readers tend to just go to the crime novel section of the bookstore? Maybe they asked a worker there what crime novels were recently popular, or perhaps they asked their friends who they knew also liked crime novels for suggestions. In other words, they very likely were using some sort of recommendation system already, just a much cruder version than what we had before Amazon.

Serendipity gives rise to big moments. An unexpected shift in detail results in the unforgettable. I think this is why we are so anxious about the potential of losing it. Big moments help us make sense of our lives—they are the major scenes in the stories we tell about ourselves. We are attracted to the idea that things may suddenly change in a fortuitous way, that a happy accident could come along and help us understand that any mistakes we had made before were leading us to this big, important moment. It wasn’t serendipity I was looking for in scouring those playlists Natalie had made for me, but it was something related to it: the “aha” moment, the moment that ties the other big moments together.

None of this is to say that serendipity doesn’t exist, or that we are foolish for our desire to find it. Rather, that the effects of technology may be exaggerated. When the Internet as we know it now was still relatively new, a great deal of research focused on information seeking — given that people had access to a seemingly infinite amount of information, researchers wanted to understand how to develop systems that helped people find exactly what they were looking for. Dr. Sandra Erdelez, in contrast, coined the term information encountering, referring to chance encounters, finding something you weren’t necessarily looking for but that was nevertheless useful in the moment. Dr. Erdelez was interested in serendipity.

In studying human information behavior habits, she divided people into three groups: non-encounterers, who were focused on finding exactly the information they needed; occasional encounterers, who encountered unexpected but useful information and ascribed it to luck; and super-encounterers, who frequently experienced serendipitous moments, and even considered it an integral part of their information behavior.

The takeaway from Dr. Erdelez’s work may be described as this: serendipity doesn’t happen to us, but instead it is a skill we cultivate. Non-encounterers didn’t have serendipitous moments because they were not open to seeing them when they occurred. Super-encounterers viewed serendipity as necessary to their goals. The person likely to accidentally discover a great new book may be equally likely to do so either in a bookstore or on Amazon. The person who does not deviate from Amazon’s recommendations likely wouldn’t have deviated from the suggestion of her friends. It is not the environment that causes serendipity, it is the person making decisions that lead to it.

Serendipity, like love, may be best served by not forgetting the everyday routines in favor of the big moments. Even if serendipity results in big moments, it is the routines that get us there, the choices we make each day on how to live our life, how we choose to see the world.

***

Several months after having realized the many choices by the many heartbroken people that affected my Spotify recommendations, I was sitting in a coffeeshop working. There was music playing softly in the background, and I caught myself quietly singing along. It was a song I knew. I didn’t initially place it, but after taking a moment, I realized why it was familiar to me: it was from “[downbeat].” I was months past the initial purge, now in a spot where I realized you never fully remove someone from your life. I give every small, black dog a second glance, thinking of Iggy. The memories never go away. At some point, I would inevitably hear one of her songs again, and now was that time.

As that song ended, and the next began, I realized: this song was also from the playlist. Two of her songs, back to back, at this moment in this coffeehouse. What a strange coincidence, I thought.

But it wasn’t. Natalie used the same song discovery tools as everyone else on Spotify. She searched for similar artists. She used the “radio station” feature. She was influenced by the small actions of millions of other people, the same way that I was in making my breakup playlist. And so that it occurred to her that these two songs fit together, and that it occurred to whoever made that coffeeshop playlist that these two songs fit together, is not such a coincidence after all. It is the result of a long process by which many people before them determined these songs are similar.

This is not to say there is no sense of happenstance here. It may be likely that these two songs appear on millions of playlists together. Still, that the songs played back to back in the time I was there cannot be accounted for by such a precise mathematics. It occurs to me though, that these are the same songs I combed through to find some hidden meaning in, some secret message about Natalie and how she felt. But there was no meaning. Her choice in picking these songs was affected by millions of other people I have never met. There is magic in the world, yes, but it is not where I was looking for it.

At the same time, guided by whatever invisible hand, she still did choose those songs for me. There was no big moment waiting for me in them, but there was something more subtle. It’s true that many of those songs do co-occur on millions of other playlists, and that’s what led her to find them. It’s far more unlikely that any playlist contains exactly all of those songs. This is the paradox. Everyone knows what it feels like to be in love, but no two loves are ever quite the same. If we think of love in terms of big moments, they might all look similar. Everyone has a first date. Everyone has a first kiss. Only Natalie had flossers. Only I had breakfast apples for Iggy. For a moment, by some luck, the two of us had each other.

Author

MATTHEW HESTON is a writer and performer living in Chicago. He recently completed his PhD in Technology and Social Behavior at Northwestern University.

Featured image: Charles Demuth, “Fish Series, No.1,” watercolor and graphite on paper, 1917. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.