I was thirty-one when Mom died, and in her absence, I asked a child’s question: Is it my fault that she’s gone?

My mother had always been the one who stayed. Dad was out of the house by the time I finished the first grade, and we saw him two weekends out of the month. Until we were teenagers, and then we rarely saw him at all. It was Mom who was always there, always home. If she left, she took us with her. We rode along in the car to the grocery store, the bank, the veterinarian, the hardware store. I was silent on those car rides, looking out the window. I mapped the places that never changed as we drove by, imagining who lived in each house, what each one looked and smelled like on the inside, and what kinds of things they had for dinner.

At home afterward, she berated me for my silence. “You hate me so much, you won’t even talk to me.” One, two, three catches, and the strike of the lighter flame. “You won’t even look at me.” Even my silence belonged to her.

Mom stayed, but she also threatened, every so often, to leave us. “How about I leave, and you can go and live with your dad?”

It seemed like something she was musing about it, turning over in her mind like a daydream, except she was angry. She was desperate. She seemed to think I might become a different child – better behaved, better able to fix her – if she came up with the right incentive.

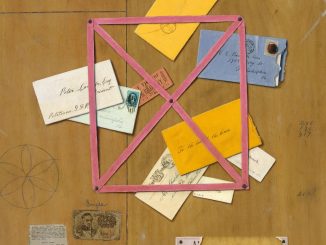

I didn’t want to leave our house or live with our dad. He would probably make us ride the bus to school. He would scoff if we asked for new school clothes, and sew up the holes in our backpacks instead of buying us new ones. I would have to write my homework assignments on scrap paper, printed on one side with something else. He wrote all his own notes and letters on paper like that, and when I came upon one lying on his kitchen table, or on the dashboard of his truck, I would turn it over, trying to decipher what the other side had been used for, how it had lost its significance and become something else. I preferred the uncertainty of living with Mom to the discomfort of living with Dad. More than that, there was an instinct, deep within me, not to be abandoned. Not even by a mother who threatened my safety.

* * *

The farm we lived on was Mom’s sanctuary. It was the soil and tree equivalent of her own flesh and blood. Though it had been there before her, it seemed to me like something she had created for herself as an oasis, a refuge. As if she had dug the earth out with her own paws.

I had to assume that Mom was happier on the farm than she would have been anywhere else, because she stayed there even after she began to struggle for freedom from it. She longed for things she couldn’t find there, for the life that had failed by some measure with my father’s departure. She was prone to angry rages and bouts of despair. The work was overwhelming. She was isolated from friendships and from the potential for romantic love. The farm became like a trap she had set for something else and forgotten about, not realizing that she might catch herself in it.

Why did she stay there, struggling in the trap? I wonder now, and I wondered then. Maybe it was the way the air smelled when we rolled the car windows down in summertime. How grasshoppers clung to your hand if you snaked it out, surfing the tops of grasses growing tall by the edge of the road. Maybe it was fear of the unknown.

Maybe it was the simple but irreversible truth we call addiction.

* * *

Occasionally, Mom reminded us of a time when she didn’t drink. I was never quite sure when this was, or how long it had lasted, since the cases of beer stacked next to the sofa had been there as long as the sofa had. Did she stop drinking at some point, but keep the empty cases? Or was she referring to a time before this house, before Dad left, when things were falling apart, but before they hit the floor?

“I used to get angry even when I didn’t drink,” she would say. As if to prove that the anger and the drinking were two separate entities, and one needn’t get tossed out with the other. And my response, which I had the good sense to keep to myself, was, “Okay, but when you drink too much, you can’t remember how angry you got.”

* * *

I’m pulling weeds in the garden. The dew has dried up and the sun is edging me out of the shade, and as I turn to empty a handful of weeds onto the growing pile at my feet, I catch a whiff of my mother on the air. I smell her sweat in the damp places of her t-shirt, and I feel the dry places, soft and warm, crumpling over the skin of her stomach. I have the kittenish urge to squeeze her flesh between my fingers, but I know if I do that she will push me away, so I don’t. In my restraint, I feel, as all children do at some point, how she is both mine and not mine.

I look around, bewildered. It’s not her sweat I smelled, but the leaves of a sage plant, their oil evaporated on the stirring wind. I bend down to take a bigger gulp of their salty, bitter scent, to clear my mind of the memory, to keep it safe in the past.

* * *

She was twelve when she took her first drink. I can see her standing, alone, in the dim light of her house on Colvin Road. It’s the middle of the afternoon, and the sun is getting lower, but the lights haven’t been turned on yet. The windows glow. In the liquor cabinet are all the bottles and jars that clink when her father pours them out in a steady stream after he arrives home from the hospital. He may leave again – to play golf if it’s the afternoon, or poker if it’s the evening – but the alcohol will come along. It will ride on his breath, warm and relaxing.

He’s not home now, though. Maybe some of her older siblings are, but they’re busy in their rooms, being teenagers. Maybe her little brother is out with their mom. She knows she’d be in trouble if they knew what she was doing, but she also knows they won’t find out. It’s because they aren’t looking that it doesn’t matter what she does. But it’s more than that: they never look unless she gives them trouble, and her trouble is never as good as her little brother’s, because he was born with his. And it’s also that her father drinks so much – so much – and no one says anything, that it has to be okay, for now, for her.

She pours liquor into a tumbler and tilts her head back.

She burns.

No one is watching.

* * *

All along the gravel road to our house, in the space before the fence line starts, my mother planted daylilies. She would weed and mow around them carefully, and sometimes, if the afternoon was not too hot, I would walk with her along the road, and she would tell me where each one had come from – this friend or that neighbor – and we would take turns pointing out the ones we liked best – the dark red, the bright yellow, the orange fading to peach, with frilled edges.

In the front garden, there were clumps of a flower she worshipped. Every year, when they came up, I would ask her again what they were called, and she would tell me with rapture in her voice, until I was finally old enough to remember it on my own: Iris, dark purple and powerful, with powder blue beards that fluttered in the breeze, and a scent that brought me back to put my face into the petals, over and over again.

The tiny crocus came up first in the spring, down by the raspberry patch, and hyacinth followed soon after. Morning glories trumpeted open and shut along the path up to the old house. I always wanted to pick these blossoms and put them in a vase inside, and Mom always said no. “Outside, they last longer,” she said.

* * *

For an addict, there is an unending struggle between drinking and not drinking. There is a physical, mental, and emotional inability to tolerate the world without a drink (or thirty) and there is the knowledge – or at least, some peripheral awareness – that the drinks are not good. They don’t make things better, except temporarily, and in between the last drink and the next one, things are often much, much worse.

Alcohol is an easy target. If there were no drink, there would be no drinking. But that’s where we get fooled, we lovers of addicts, we children of alcoholics. Because it’s the person that’s the problem, not the alcohol. The alcohol seems like the thing to fear, but it’s change that we are most afraid of.

Addiction itself is a cycle of blame and punishment, a negotiation between the good and bad within you. I’ve never been addicted to a substance – I can’t even drink coffee – but there are some things I have an unhealthy attachment to: birthday cake, right answers, the illusion of perfection, certain degrees of emotional pain. Most of what I know about addiction is secondhand. I’ve seen the constant pull between using and not using, whether to drink or not to drink, and although I don’t know it for myself, I do know that, for the child of an addict, there is no such struggle. There is only the truth of how love goes away when your parent is drinking, and it only comes back when she stops. Love is presence, attention, sobriety. Every time Mom drank again, she was making the choice to leave.

* * *

On the farm, the red bud trees bloomed next to the outhouse, and in earliest spring, there were gluttonous clumps of daffodils growing in the shade of the old house. One morning, before school, Mom sent us outside early to pick them by the dozen. We divided them among canning jars filled with an inch or two of water, one for every teacher in our school.

It was unusual to be outside so early, crouching in the dew, and I shivered a little, intent on my work and relieved when we were done so my legs could dry in the air before we got in the car to go to school.

I felt so proud visiting each classroom, delivering the flowers as gifts to the teachers who always seemed delighted by my brightness, who may have thought I was strange, but were too grown up to tease me about it like the other kids did. If nothing else, they were grateful that I wasn’t one of the ones who made trouble in the halls, and grateful also for the flowers, though no matter how much they exclaimed over the bright yellow blossoms, bobbing about as we handed them over, I could never shake the feeling that they didn’t really understand how beautiful daffodils are.

Author

DOROTHY NEAGLE lives and writes in Hastings on Hudson, New York. In addition to writing fiction and poetry, she recently completed her first full-length memoir. She gravitates toward topics like grief, survival, and fear, striving to follow Amy Goodman’s advice: “Go to where the silence is and say something.”

DOROTHY NEAGLE lives and writes in Hastings on Hudson, New York. In addition to writing fiction and poetry, she recently completed her first full-length memoir. She gravitates toward topics like grief, survival, and fear, striving to follow Amy Goodman’s advice: “Go to where the silence is and say something.”

Instagram: @sentencesaremyfave

Featured image: Winslow Homer, “Flower Garden and Bungalow, Bermuda,” watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper, 1899. Amelia B Lazarus Fund, 1910. Metropolitan Museum of Art.