Once, long ago, I came face to face with a deity, an earthy god in Peru, and the meeting did not go well. More accurately, I crossed paths with an ancient god’s effigy deep inside a buried temple. It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God, wrote St. Paul. Maybe so, but I have to take the apostle’s word for it. My own experience—ending up nose to nose with a dead god—was no picnic, either.

This encounter took place in the ruins of Chavín de Huántar, a ceremonial center that one of South America’s oldest, most influential pre-Columbian cultures built in fifteen stages between 1200 BCE and 800 CE. (The Inca empire, by contrast, flourished much more recently—between 1425 CE and 1532 CE.) Abandoned for over a millennium, the Chavín culture’s religious center lay in ruins and received few visitors until the mid-twentieth century.

A longtime friend had joined me in 1977 for a trek to Chavín. Scott Thomas and I, having met in junior high school, had hiked and camped together, mostly in the Colorado Rockies, over a period of many years. During the mid-Seventies, we had speculated about traveling to Peru. Now our trekking junket had begun. We flew to Lima and traveled overland to Huaraz, a small city in the north-central Peruvian Andes that would serve as our urban base camp for trips into the mountains. At some point, however, Scott informed me that a college friend of his, Peter, would be joining us. I hesitated to object despite feeling concerned about the changes in our collaboration. Peter arrived, settled in with us, and then, a day before our planned departure, announced that two of his own friends, Jane and Dave, would be coming along as well. To complicate matters further, Scott suddenly fell ill with a severe intestinal virus and felt too sick to make the trip. With Scott sidelined, I abruptly found myself heading into the hinterlands with people I didn’t even know.

I felt uneasy around Peter from the start. Talkative, funny, and clearly bright, he seemed an affable con man. He was good-natured as he manipulated people around him but manipulative all the same. His frequent comments about drug deals alarmed me. “Scoring coke here is like buying sugar,” he announced. I asked if he worried about getting busted. “Busted?” he exclaimed with a laugh. “Hell, no! Even if you get caught, possession is a bribable offense.” When I expressed concern about my possible guilt by association, Peter brushed off my worries. I felt angry and appalled that he would disregard my feelings on an issue that could land us all in jail. “It’s nothing to get so uptight about,” he noted, adding with a laugh: “If you think I’m bad company, you don’t really have to join the trek, do you?” I could have pointed out that he was actually joining my trek, but I decided to hold off. Peter dismissed the point. “Let’s just go there, okay?” he said. “There’s safety in numbers.”

Jane and Dave? A twenty-something couple from California, they seemed cordial enough and at least showed no interest in drug deals. On the other hand, they manifested some attitudes I’ve found common and troubling in people who have visited so many places—in their case, dozens of countries over a period of several years—that they’ve become jaded. Nothing inspired their curiosity. New places seemed important chiefly as names to cross off a list. Landscapes, people, history, languages, art, cuisine, customs: everything struck them as irrelevant, problematic, or uninteresting. These attitudes held true regarding north-central Peru. Worse yet, they expressed criticism and even contempt for almost every aspect of what they encountered. Peruvian food was bad, the hotels uncomfortable, the locals annoying, the language confusing, the customs a nuisance. “Peru is supposed to be such a cool country,” Dave commented during an early conversation. “Frankly, I think it’s overrated.” I had joined forces with fellow travelers who regarded our venture as a waste of time from the outset.

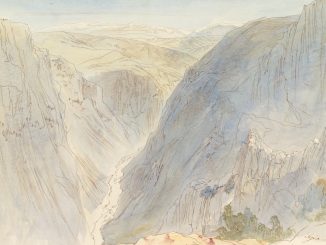

On June 30th, the four of us hitched up the main valley to a town called Olleros, then hiked several miles on a steep dirt road heading due east. Most of this region, the Callejón de Huaylas, is spectacular—a hundred-mile-long valley flanked by two Andean cordilleras, one of them the world’s highest equatorial mountain range, its summits reaching over 22,000 feet in altitude—but our route was less remarkable than other places I’d seen in the area. Yellow-brown grasslands rolled away in all directions without offering any views of the glaciated peaks. This was puna, high tundra covered with tan, tufty ichu grass. The hiking offered a sense of relief, however, after many days of inactivity in Huaraz. Even so, I felt uneasy to be undertaking a major trek with these disagreeable companions. Would they be competent hikers? Could I trust them in an emergency? Would we get along?

***

After that first day’s walk, we camped at around 14,000 feet. The site was typical of the puna. I saw no signs of people or livestock. I was already accustomed to backpacking in the Andes—I had trekked for several weeks during a trip in 1971—so I knew that our surroundings weren’t unusual. I also knew that despite the barren landscape, this place was probably inhabited. What foreigners often perceive as exotic wilderness in Peru is what the campesinos, the indigenous residents of these areas, would regard as just an ordinary rural setting. I knew we had probably pitched our camp on someone’s grazing land. Was this land held in common by local villagers? Or did it belong to a specific family? Either way, we were trespassing. Local customs generally allowed respectful parties to cross the land, even to camp there briefly. I felt neither surprised nor alarmed when a middle-aged man stopped by that evening to visit us and, I assumed, to assess our intentions.

Like many male Andean mestizos—men of mixed Spanish-Indigenous heritage—he wore clothing that to an American, at least, looked incongruous: homespun woolen pants, tattered V-neck sweater, baggy woolen sports jacket, and misshapen fedora. (Men of fully Indigenous background probably would have been attired in tire-soled sandals, knee pants, homespun cotton shirt, and woolen poncho.) This man, fortyish in age, looked as if he might have wandered away from a business meeting years ago somewhere in a coastal Peruvian city but had never changed his outfit. He appeared at once dapper and bedraggled.

“¿De dunde vienen, gringu?” he asked me in Quechua-accented Spanish—Where are you from, Foreigner?

“Colorado,” I told him, avoiding mention of the United States.

He nodded gravely. “¿Es parte de lus Estadus Unidus?”

“It is,” I admitted, then changed the subject: “We’re hiking to Chavín so we can see the ruins.”

Another nod. Campesinos I had spoken with in the past often expressed amazement that foreigners would choose to walk long distances when they could have ridden. Why, too, would anyone travel so far just to see mountains and ruins? He probably couldn’t comprehend why we gringos would expend so much effort and expense to visit such a remote place. In any case, I wanted to reassure this man that we wouldn’t linger. Outsiders often inspire anxiety among the Indigenous population—an attitude that’s neither surprising nor unjustified, since Europeans and Americans have caused them so much damage and grief ever since the Spanish conquistadores first showed up in 1535.

“May we camp on your land for one night?” I asked.

“Sí, está bien.” I detected neither hospitality nor enthusiasm in his words, only cautious consent.

We continued chatting. I wanted to put this man more at ease, to show him that we presented no threat to him or his family. We were just four gringos passing through. We discussed the land, the weather, and the reasons why foreigners visit Peru to hike and climb mountains. I don’t remember how or when, but somehow the discussion turns to pishtacos. I had heard about these mythical figures as a teenager—also known as pishtacus or pistacus—back when my family lived in Lima for two years during the 1960’s. According to Andean folk mythology, pishtacos are henchmen of the devil who appear unexpectedly to perpetrate sinful deeds—kidnapping children, murdering adults, even cooking them to render their body fat. These evil creatures often resemble European males: tall, bearded, and boot-wearing men. Hearing mention of pishtacos while talking with this landowner—I myself being bearded and booted, though tall relative only to the often short campesinos—made me nervous. At some point, speaking calmly, he said, “Quizás tú eres un pishtaco.” Maybe you are a henchman of the devil. This oblique accusation was a worrisome turn of events. What would this man’s speculation mean about his attitude toward us—or about his possible actions while we trespassed on his land? If he believed we were henchmen of the devil, what might he do to us? During my family’s mid-1960’s stay in Peru, a Peace Corps volunteer had told my parents that an American he knew, a young priest living in the same Andean village, had been accosted one night and killed, his throat slit, because of rumors that he was a pishtaco.

The man and I chatted for a while longer. Peter, Dave, and Jane, who spoke almost no Spanish and showed neither interest in nor respect for our host as I talked with him, didn’t join the conversation. All three of them acted rather miffed that anyone would bother us while we fixed our supper. Then, after I assured the landowner once again that we would leave in the morning, he turned and walked off.

***

We passed the night without incident. The dreadful fantasy I envisioned on going to sleep—that the campesino would come back and nip our deviltry in the bud—never came to pass. My companions and I woke at dawn, ate breakfast, folded our tents, and packed our gear. We then set off and continued hiking up the valley. Once again the scenery was unremarkable, just a scattering of peaks with small glaciers descending from their slopes, drab puna. The hiking wasn’t hard, but the effort felt tedious. The wind slapped us. The scenery offered no solace or inspiration. Even so, I felt eager when I grasped that we would reach Chavín within five or six hours.

Having broken camp at nine, we cleared the pass by eleven. A downhill path now lay before us. Yet the hiking grew more difficult despite our now having gravity to our advantage: descents can be strenuous. We were passing through the Quebrada Huachecsa, one of the steepest gorges in this section of the Andes. The trail was wide but uneven and rocky. Even a minor slip could have caused a major accident. The final stretch took us down a massive trench whose granite walls rose almost vertically on our right and our left. Then, as we neared Chavín, I saw the drab little village and, off to the right, the excavated ruins. The site looked much more extensive than I’d anticipated.

Walking into town, I felt relieved to have finished our trek. Jane, David, and Peter had been able hikers. We explored the town center—low, whitewashed, tile-roofed houses clustered around a dusty Plaza de Armas—and we managed to find acceptable lodging. Like many such hotels in backwoods Peru, this one consisted of four one-story structures forming a square-sided O and facing a central courtyard. The buildings’ adobe walls were crudely plastered and whitewashed both inside and out. The rooms were monastic: two beds, a rough-hewn table, a chair, and a single window looking out onto the courtyard. Each bed consisted of a sagging straw mattress, threadbare sheets, a single blanket, and a pillow. I had grown accustomed to such hotels throughout my travels in Peru; I almost enjoyed their austerity. This one would serve our purposes, especially since there would be nothing better in a little town like Chavín. Peter and I would share one room; Dave and Jane would take another. In the courtyard, rabbits hopped about while some children chased one another, shouting and laughing. In short, the place was a provincial Third World inn much like those I’d come to know well during my earlier travels.

We settled in. We all felt so tired that we didn’t venture out that afternoon. We napped, then walked to the Plaza de Armas, sat there for a while, returned to the hotel, and read our books. That evening, the four of us ate dinner at a scruffy little restaurant. Both before and after the meal, we drank beer at a different café. The town was quiet and dark. I was exhausted.

***

During the 1970s, Chavín was a well-known but rarely visited archaeological site. The town and the site received little attention compared to, say, Machu Picchu, located almost four hundred miles to the south; few foreigners in Peru, most of whom zeroed in on the famous “Lost City of the Incas,” ever trekked to the much older site where I now found myself. Located at an altitude of 10,500 feet a hundred fifty miles north-northeast of Lima, Chavín is the remnant of a civilization that draws far less attention than the Incas’ iconic ruins. Western visitors had “discovered” the site during the late nineteenth century, but indigenous residents of the area had surely known about the ceremonial center from time immemorial. Little information about the site’s origins and purpose became available until the 1990s. Although early twentieth-century archaeologists grasped that the Chavín culture predated the Incas by many centuries, they significantly underestimated its age. Initial guesses dated construction at between 800 CE and 1200 CE. During the mid- and late 1990s, however, John W. Rick, a Stanford University anthropologist, used radiocarbon dating to determine that the Chavín culture actually finished building its city by 800CE. These estimates of the culture’s development make the site many centuries older than Machu Picchu, which the Incas constructed during the 1400s. For this and other reasons, some archaeologists compare Chavín to the Sumerian ruins in Mesopotamia, both because of their age and because of the past inhabitants’ profound influence on later civilizations. My longstanding interest in pre-Columbian cultures had prompted me to visit Chavín.

***

I awoke in pain. My knees ached, felt warm to the touch, and looked visibly swollen. The discomfort and swelling baffled me. Eighteen months later, after experiencing multiple episodes of similar symptoms, I would receive a diagnosis of sero-negative polyarthritis, a poorly understood form of joint disease, but in July of 1977, I didn’t know what was happening. All I knew was that my knees had puffed up so much that I could scarcely walk. I guessed that the swelling resulted partly from my descent on the long, steep trail down through the Quebrada Huachecsa while carrying a forty-pound pack, but I had no idea how to remedy the swelling. I took two Tylenol and hoped the discomfort would ease. I joined my companions at a little café near the Plaza de Armas, where the teenage waiter served us the only available breakfast: reconstituted milk and stale bread. The four of us talked for a while, reviving, then set out for the ruins.

Walking toward the site, I couldn’t see much of it as we left town. Soon, however, a grassy plaza came into view. I also saw several huge mounds flanking the site’s entrance—temples? pyramids?—along with a series of dilapidated walls and the remnants of a staircase slanting against a two- or three-story story structure. Compared to other Mesoamerican and South American sites I’ve visited—Machu Picchu and Chan Chan in Peru, Uxmal and Chichén Itzá in Mexico—Chavín had a veiled, perplexing appearance. Only decades later would archaeologists fully excavate the ruins that in 1977 remained a dirt- and grass-covered state; and only then would they begin to understand the site’s full extent and its likely purpose. I had read, however, that the ruins’ still-buried condition wouldn’t be an obstacle to glimpsing what’s most important about Chavín. The secrets there don’t lie on the surface but underground, in a maze of tunnels and chambers.

The four of us wandered for a while among the ruins to view the dilapidated temples and plazas. The religious center lay at the base of a tall, broad hill—what would have been a mountain in most places but didn’t count for much in the Andes. Grass covered the plazas and the horizontal surfaces of many terraces. Staircases rose from the plazas to the temples. Many of the stone walls, though less tightly constructed than the Incas’ much later masonry, struck me nonetheless as impressive. Peter, Jane, Dave, and I explored these areas for twenty minutes.

Then, locating the entrance to the Old Temple, we entered a dark passageway. We had brought only two flashlights to shine a path for all four of us. One of the lights was mine, fortunately, and I insisted on keeping it in my possession. Dave held the other. These two scant beams provided only enough light to make our way in. We groped our way forward with only the barest sense of what lay around us. The subterranean passageway smelled like a cave. I felt we were creating more darkness than we managed to dispel. Worse yet, we saw other hallways branching off from the one we had entered. We had entered a labyrinth. What if we got lost underground? What if the flashlights failed? At some point we heard footsteps behind us: not a welcome sound. Turning, we saw a pall of yellow light approaching. “¿Necesitan ayuda?” asked a low voice. Do you need help? Although initially uneasy to have a stranger join us in this claustrophobic place, I soon felt relieved that the ruin’s caretaker—a dark-skinned, middle-aged man wearing rough woolen trousers, a sienna-colored poncho, and a rumpled fedora—had followed us in. Holding a kerosene lantern, he offered his assistance.

We proceeded down the hallway. With the path now more amply illuminated, we could see far more of our surroundings. Even the lantern couldn’t push away the darkness farther than twenty feet ahead, however, and the stones protruding from the walls on our left and right cast shadows ahead of us. The caretaker made a few comments about the site, his Quechua accent so thick that even I, fluent in Spanish, couldn’t follow his narration. Soon we continued in silence.

Then, almost without warning, we reached the lanzón—Chavín’s Holy of Holies. Four and a half meters tall, this effigy stands in its own chamber at the intersection of two corridors. The caretaker held up his lantern up for us to see the massive carved pillar. A jaguar face leered at us from atop a human body. A mane of snakes sprouted from the head. Fangs protruded from the mouth. Eyes peered at us from all over. The yellow lantern light, shifting, made these features move as if alive. I felt the creature’s crude, bloody holiness. Gazing at this idol, I responded in ways I never had before in such a place: I felt sick to my stomach, I broke into a cold sweat, I felt faint. I was afraid in ways I couldn’t explain or control. I worried about passing out. Then the reaction diminished. I kept looking, still uneasy but feeling a less visceral response. I listened to my companions make their dismissive comments. Dave said, “Well, whatever floats your boat.” Peter said, “Wonder what kind of drug the sculptor-dude was taking.” Then we turned, following the caretaker back through the labyrinth, and emerged into the sunshine.

***

Our visit to the ruins continued for a while longer, then spun itself out. Peter, Jane, and Dave traded complaints about how disappointing they found Chavín—“Not a tenth as good as Machu Picchu,” Dave noted. Feeling restless and exhausted, I kept to myself, said nothing, and brooded about my own experience inside the ruins. The others wanted to keep wandering, however, so I followed them briefly, then retreated to the town center once their interest in the site guttered out. I returned to the hotel. Achy and tired, I slept for a while. Ignoring the others when they showed up again, I ate bread and peanut butter in my room rather than joining everyone else at a local restaurant. I kept to myself through the afternoon: sat in the courtyard and read. Although I wanted a break from my companions, I also needed time and solitude to ponder the day. What had I experienced deep inside the ruins? Why had the stela unnerved me? What was the significance of the revulsion I felt toward its primal features?

Nothing came of my brooding, but a sense of unease lingered.

Later, the four of us joined up again to find some dinner. We circled the town square and stopped at each of the several restaurants to ask what they might be serving. Typical of provincial joints in the Andes, each place posted a small black slate listing the day’s menu in chalk letters. Lomo saltado, pescado frito, cuy al horno . . . All four of us had traveled long enough in Peru to know that these offerings were theoretical, not actual. When we asked one of the restaurant’s waiters about, say, lomo saltado, he replied, “Se acabó”—It ran out. How about the pescado frito? “No hay”—There isn’t any. What about the cuy al horno? “Todavía no”—Not yet. This litany of requests and negations prompted Peter to exclaim, “These people are so damn negative! Their five national mottos are No hay, Todavía no, No se puede, Se acabó, and Está prohibido. No wonder they never get anything done!” I commented that it must be hard to live in a place where scarcity was the norm, not an aberration. “Given their negativity,” Jane responded, “it’s no wonder everything’s so scarce.”

Eventually we settled on the Restaurant Santa Rosa, right off the plaza. It was so dark and dingy, just a few tables in a single room full of smoke from a wood-fired stove, that we questioned the wisdom of eating there at all. Seeing no better alternative, however, we went ahead. The meal: fried eggs with fried potatoes. We ate in near-silence. I felt relieved to have a break from my companions’ complaints. There were some distractions as well. Three drunk teenage campesinos sat at a nearby table, one of them singing pentatonic songs in Quechua to his pals. At some point a little boy and a pubescent girl emerged from the kitchen, seated themselves at our table, and proceeded to do their homework while we ate. I enjoyed having them present—they were much more congenial company than my fellow travelers. “What is nine times six?” the little boy asked me in Spanish. The girl showed me her grammar lesson. Jane, Dave, and Peter grumbled about these kids disrupting our meal. I ignored the gringos and chatted with the children. Nearby, a fedora-hatted woman in a dirty white cotton blouse and long woolen skirts ate soup beside a flaring stove in the otherwise dark kitchen. Several cats and dogs roamed around us, begging for food. Our waitress, a girl fourteen or fifteen years old, repeatedly asked us, “¿Tiene monedas de su país?”—Do you have coins from your country? Then, after the drunk teenagers got up and staggered outside, she locked the door and braced it with two chairs. One of the drunks shouted at us from the other side of the barricaded door. The four of us gringos finished our meal, lingered in the restaurant, and left only when the shouting ceased. We walked back to our hotel. I felt relieved to disengage from the group.

I took a long time falling asleep that night despite severe fatigue. My throbbing knees disrupted me, though less so than my throbbing mind. I couldn’t shake my bewilderment about the day’s events. My recollections of walking through Chavín’s dark passageways continued to disturb me. Encountering the ancient images had literally sickened me. To find bats, serpents, and a jaguar-faced god greeting me where the hallways met! The weak lantern light and the flashlight’s jumpy beam made the stone faces shift as if alive. The lanzón: full of teeth, claws, and multitudinous eyes, this image alarmed me more than any ancient idol I’d ever seen. But why? Was my visceral response a result of the monolith’s own properties? Could my physical state—fatigued, pained, agitated—explain my dizziness and revulsion? Could my dislike for my companions and my unease in their presence have heightened my already tense state of mind? Or was it possible that the lanzón itself, its origins and its nature, possessed some kind of inherent negativity? Ever since my teens, when I’d heard hippies refer to the “vibrations” and “auras” they ascribed to various objects, I had dismissed these notions as New Age hooey. Had I been too quick to brush off these notions? Perhaps an ancient stone could have a presence, an essence. If not exactly evil, then perhaps chthonic—earthy, earthly in the deepest sense of the word.

These thoughts plagued me for hours. At some point I fell asleep.

***

I awoke to find the morning dark and cloudy, rain falling, though the sky had been clear the night before. Somehow I had slept fairly well, which surprised me, especially since I had roused at one point on hearing someone pound on the hotel door— perhaps the same trouble-making teenager at the restaurant?—until the hotel’s half-senile owner shouted at the tosspot in Quechua and convinced him to leave. My disquiet lingered, though I felt relieved to find my knees less swollen than the day before. I also felt my energy surge when I grasped that I would soon leave Chavín, return to Huaraz, and disengage from Peter and his friends.

On stepping out of the hotel and walking over to the Plaza de Armas, I learned that cargo trucks routinely drive west from Chavín and cross a pass into the Callejón de Huaylas. If I’d known about that route earlier, I could have spared myself three days of my companions’ presence. The plus side: now I wouldn’t have to walk the whole way back with them. I quickly managed to locate a Huaraz-bound truck. I arranged for the ride with the chofer, who told me to come back in an hour; then I joined the others for breakfast at a new restaurant they’d discovered. After eating, we returned to the Plaza de Armas, climbed up the truck’s slatted wooden side into the cargo box, and nestled in among the gunny sacks of potatoes, onions, and apples heaped there. Five or six campesinos joined us on the pile of produce. The truck set off. We zigzagged up the mountain road; the puna opened up around us; and we proceeded to the pass, where a crude, unlighted tunnel crossed through the ridge into the Callejón de Huaylas. Then we worked our way down a sequence of alarmingly steep hairpin turns until we reached the valley floor. On the wider, less-steep main road we proceeded to the town of Catac. There Peter and I, leaving Dave and Jan on the truck, switched to a local bus. During our descent toward Huaraz, I felt alternating waves of impatience and serenity. The weather somehow reflected my mood: scudding clouds and tassels of rain suspended over the massive valley.

In this way the trek to Chavín concluded. I found Scott at our Huaraz hotel and discovered with relief that although he remained sick, he had coped adequately while alone and was starting to recover. I myself felt physically better, too—less exhausted, less achy. Returning to a larger town boosted my spirits. Although I felt crestfallen when Peter announced his plan to linger in Huaraz with Scott and me, I knew I would now have far more options for avoiding him. My mood lifted.

Scott and I left Huaraz later that week. We planned to spend a few days in Lima, then proceed south to Cuzco. Mercifully, Peter had preceded us after all—he planned to meet up with some cocaineros in the capital to close a drug deal—and his departure granted Scott and me an early release from his company.

***

Throughout the decades since my visit to Chavín, I have pondered my trip there and what I experienced in the ruins. Archaeological research since the late 1970s has revealed many aspects of the place and has clarified the nature of the ancient culture whose members built the religious site. Dr. John Rick’s excavations, especially, have illuminated significant issues. Starting in the 1990s, Rick and his associates excavated not only burial platforms and ceremonial plazas; they also discovered a remarkable maze of underground galleries beneath the ceremonial complex. Their findings have helped to solidify understanding of Chavín’s role as a cultural and religious center. Throughout the site they have found pottery, relics, ceremonial objects, so-called strombus (conch) trumpets, and idols. These and other artifacts have cast light on many features of the site, including the lanzón, the five-meter-tall monolith that depicts the Chavín culture’s supreme god: the jaguar-headed, snake-haired, wildly fanged human that I had faced and had found so alarming at the intersection of underground passageways.

Based on these discoveries, John Rick’s most radical notion is that the layout of Chavín, as well as the artifacts found there, strongly suggest an evangelical purpose: to convert the uninitiated. The labyrinth of tunnels and chambers appear to have been pathways to an inner sanctum. Also suggestive is the discovery of shiny coal “mirrors” that probably allowed the priestly elite to reflect sunlight into the tunnels. In addition, drainage canals hint at the possibility that priests and their acolytes ducted running water into the chambers to create loud, disorienting sound effects. How did these sensory barrages affect the people who experienced them? Dr. Rick speculates that initiation rites subjected pilgrims to sights and sounds that would overwhelm, confuse, and influence them. Using the maze of passageways as a disorienting venue, the priestly elite manipulated light and sound, immersing supplicants in a participatory son et lumière experience. The rituals would probably have started with novices ingesting a hallucinogenic substance derived from the San Pedro cactus. As the initiates worked their way through the dark, cramped hallways, the sound of conch trumpets echoed around them from unseen sources. Water roared through canals beneath their feet or even overhead, producing bizarre noises that the drugs would have intensified. Mirrors placed in ventilation ducts to reflect the sun would have poured brilliant shafts of light into the subterranean hallways, perhaps to be blocked abruptly at crucial moments, immersing the supplicants in total darkness. By the time the subjects emerged from the chambers, staggering and stunned, the experience would have changed their perspective forever. “The priest-elite of Chavín,” Dr. Rick has written, “seem to have been creating a new sensory environment in which belief in the normal world is suspended, and assertions of otherworldliness [by] these religious authorities would have been made credible.”

I’ve read about John Rick’s discoveries in archaeological journals, and I find his theories plausible. The artifacts that he and his team have unearthed, as well as their further excavations of the galleries, make a strong case for Chavín having been a pilgrimage center. What, then, does this research mean about my own experience? Had I become an inadvertent pilgrim when I entered the dark hallways? Had I done obeisance to the ancient jaguar god? When I felt physically ill at the sight of this god’s many-eyed, multi-fanged visage, had I grasped some kind of mysterium tremendum? Typical of my always-ambivalent, always-skeptical responses to such experiences—to almost all experiences—I don’t know. Something happened. Something intense. Something complex, inchoate, bizarre. But I’m not sure what. I’m not sure why. Was it possible that my fatigue and physical discomfort, including the early symptoms of a rheumatoid condition, predisposed me toward agitation? Was it possible, too, that my worries about Peter’s drug deals and the risk of guilt by association had left me feeling hyper-alert? Or that my unnerving encounter with the campesino on our trek’s first night—the landowner who implied that I myself might be a henchman of the devil—might have fostered primordial anxieties? These and other concerns may have set the stage for my gut-wrenching, sweat-drenching response deep in Chavín‘s subterranean Holy of Holies. In any case, it seems that even absent the once-loud rushing water, the once-bright reflected light, the once-unnerving conch trumpets’ blare, and the once-psychedelic effects of the San Pedro cactus: absent of all these factors, I had still suffered the effects, or perhaps benefited from the effects, of the long-dead priests’ evangelical gambits. Or perhaps—to put the situation less charitably—I had simply ended up like Adela Quested, the young schoolmistress in E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, who enters an ancient cave, suffers disorientation and anxiety inside its void, and emerges shaken but unsure of what she had experienced.

There’s a further aspect of the process I’ve undertaken toward understanding what happened to me early in July of 1977—a dose not of psychedelics but of ambiguity.

In the mid-1990s, while doing further research about Andean cultures, I stumbled on this passage in a recent guidebook: “Here [in the ruins of Chavín], at the intersection of crossing passageways, was discovered the large monolithic dagger stone, the lanzón. The original is now in Lima; however, a full-sized replica effectively occupies its place.” I stopped reading. I paused. I went back to the start of the paragraph and reread it. “ . . . a full-sized replica . . . “ The realization hit me like a slap. I had been spooked by a replica. The effigy that had induced nausea, chills, and malaise inside the subterranean passage was a fake. A well-wrought fake—but a fake all the same.

What did this mean, to be spooked by a fake? Was my reaction pointless, ridiculous, silly? Had I become upset over something that wasn’t “real”? If I had felt nausea, chills, and malaise on seeing the actual lanzón rather than a replica, would that have been a more legitimate experience? Maybe, but maybe not. An African American seeing a noose dangle from a tree, or even seeing a sketch or a photograph of a noose-dangling tree, would have every reason to feel sickened and appalled even though that specific tree might never have been the site of an actual lynching. A Jew would have every reason to feel appalled and sickened upon seeing a wrought iron gate bearing the slogan ARBEIT MACHT FREI—even if the gate were only a replica. Indeed, any feeling person, whether African American, Jewish, or of any other background, would rightly feel revulsion and dread toward these icons of cruelty and hatred whether the objects were “real” or “fake.” Why shouldn’t I have felt unnerved and sickened on seeing chthonic imagery that felt threatening despite the bats, snakes, and jaguars being only a twentieth-century stonemason’s mimicry of the ancient stela? The stone itself struck me as inherently, almost radiantly evil. Yet it wasn’t. It was just a stone.

I had suffered the fearsome presence of a dead god, or of a dead god’s image. But perhaps the fear I felt toward what seemed inchoate evil, as well as the struggle I fought in response, wasn’t deep inside Chavín’s ruins after all. In the words of Mahatma Gandhi, “The only devils in this world are those running around in our own hearts, and that is where all our battles should be fought.”

Author

Born into a multicultural family (Mexican/German-American), E. J. MYERS was raised in Colorado, Mexico, and Peru. After attending Grinnell College and the University of Denver, he worked in various professions and trades, including inpatient health care, emergency medical services, cabinetmaking, and freelance writing. He lives in central Vermont.

Featured image: Still image of the Lanzón Stela at Peruvian archaelogical site Chavín de Huantar, from full video viewable at cyark.org.