“If you came here over a couple years ago your file is probably archived.” I could hear on the other end of the line the same woman who had handed me a water bottle while I sat in the waiting room of First Stone Ministries, a reparative therapy center in Oklahoma City. “I can look it up for you in Stephen’s files, but it won’t be today. Maybe early next week?”

“Okay, that’s fine.”

She called me back a few minutes later.

“I’m sorry to bother you, but did you come with a parent? You said you were a minor?”

“Yes, and my mother took me.”

“I’m not seeing your name, or your mother’s name, anywhere here. If you can recall, did you want to be here?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“So, if you were a minor and came to our program, no matter how long it was, a day or a week, and you expressed that you didn’t want to be here, or left the program without completing it – if you were a minor, we terminated your file. We don’t keep records on people who just don’t follow through with the program.”

“You don’t?”

“No. And the reason why is because we are very careful, especially with minors, to not push unwanted ministry on people, because it could make the situation worse. Our purpose at FSM is to heal and not to hurt. Is there anything else I can help you with?”

I pressed the large red circle at the bottom of the IPhone, setting it on top of the cluttered marble counter I sat at. The papers made a crinkling sound, like folded foil, when I sat the phone on them. I pushed myself back into the seat, not feeling any motivation to get up and move, except for my head, which I turned to look out the open living room window. The reflection of the television hit the glass, translated as a blurred image. There was no sound. The television was on mute. The face of President Trump was distorted by the window glass, resembling an early Pablo Picasso painting. Falling snow was juxtaposed onto his face, quietly falling onto my garden outside, filled to the brick edging with dead flowers. The remnants of decaying milkweed, primroses, and lilies draped over the popcorn pattern of the white bricks.

A buzzing sound brought my gaze back to my laptop where a Facebook notification appeared at the top right-hand corner of the screen. I ran my fingers along the smooth mousepad, clicking on the notification, opening up the website, which gave me some type of relief, knowing that Averi had responded. Our friendship had faded away and now we were in different states, attending different colleges. On my last day at FSM, I had had a panic attack and ran out of the dense, dark, gray building into the warm Oklahoma sun, feeling freedom when I saw leaves fly across the concrete parking lot. My mother stayed inside for an hour and a half, talking to my ex-gay therapist. When she got back to the car, we both cried, and I think she knew that she had made a mistake. Averi picked me up that afternoon and took me to a coffee shop in Lawton. We sat by a street-side window, watching the cars pass by. I didn’t know what to say to her. She didn’t know what to say to me. She just smiled at me, moving the hair from her pixie cut away from her face. It was a smile that had a hint of worry in it.

“Hi, Averi. I hope you are doing well,” I had texted her. “I’m trying to figure out when I went to reparative therapy. I remember that after that last day, you came to my house, picked me up, and we went to get coffee. I can’t remember a lot of stuff that happened in that period of my life. It’s all a blur. Can you give me any information on when, or how long, I was at that place? I called the institution and they told me they don’t keep records of people who didn’t finish the program.”

My eyes moved across the text where she had responded. “I was sixteen in 2014 and that was our sophomore year,” she said. “I was driving a black truck that year and in 2015 I had a silver car. I hope this helps. I can’t remember what we talked about because it was all a blur to me too.”

I sighed. She didn’t help as much as I thought she would have, but at least I had evidence that it all happened in the Spring of 2014, remembering how my mother pulled into the driveway occupied by Averi’s black pickup.

Books sat on one end of the counter, some of which were textbooks and novels that were required reading from my latest semester of college that I never got to put back on the bookshelf. I had stacked them from largest to smallest. A book of Rembrandt etchings was at the bottom, which I was looking at when my mother first told me she had found a place that she said would help me. I didn’t even have to look at it to imagine the page that I clenched when she had told me. The winkles were still visible in the paper, running across the face of Abraham, holding a knife in one hand and covering Isaac’s eyes with the other. Before that day, my mother had taken me to two different counselors in Lawton. My printed records from both quietly sat next to the books that begged to be opened. I remember the strange feeling of talking about my sexuality with two women, who I later learned had no credentials and how, when my mother asked if my testosterone should be tested, they smiled at her, saying, “Satan doesn’t show himself through a testosterone test. This isn’t our first case of homosexuality and all the parents want to do the test. When they do, it all comes back the same. Normal.”

Rubbing my forehead out of frustration, I sat my glasses down on a stack of printed excerpts from FSM’s website. On top, was a list of success stories that the institution used to advertise. My mind raced, trying to find resonance in the bulleted list of sentences that I repeatedly read, once again asking myself if it is truly possible to be ex-gay, questioning if the hard times that I had faced during my teen years were truly created by my own sin. Would I still have been able to become a preacher, like my family had wanted me to be, if I had stuck with it and had been converted in the small semi-circle rows of chairs in the FSM therapy room? Would I still have a deep, personal relationship with my family? Would I still have the feeling of God in my life? I read the list of stories over and over again, finding no resonance with myself.

– A pastor’s son was molested, overcame his sexual sin, and ultimately became a minister himself.

– A man trapped in fear and sexual perversion, caused by the ritual abuse of a Satanic Occult, was once again able to sleep at night.

– Multiple men, shamed by the media for their participation of sexual sins in public places, were able to go on with their lives in the healthy path of Christ.

With those words, the hope of being ex-gay faded. I had avoided the success stories for so long, afraid that they would have been realistic enough to question whether the past few years of not trying to change had been a waste of a life, that, one day, I could return to the Mennonite-Brethren church I was raised in, or not be ashamed when a member of the congregation spotted me in public. It made me tear up to think that I could run into a member of the church and not see a disgusted expression run across their face. Perhaps, I could even carry along a conversation with them, both of us smiling, or the person standing from a distance, whispering to their child the story of how I had overcome sin. FSM’s success narratives ran these hopes out of my brain, telling me that I’ll never have the life I wanted.

The palm of my hand rested on the stack of papers, as I thought of who might have written the stories that I assumed were blatant lies. Narratives that never occurred. And I thought of my ex-gay therapist Stephen Black. His cold skin. Hefty body. White hair. The bags under his brown eyes. Rolling himself over to the tan couch where my mother and I sat, smiling, blatantly telling us that he had no qualifications, other than being an ordained minister. His feet, miniscule compared to the rest of his body, tapping at the floor, almost echoing the same beat as my shaking hands that grasped the red pillow in my lap, my eyes focusing on an embroidered Bible verse on the top of a shelf, adjacent from the couch. The verse combined two different parts of the chapter, John 8:7 and John 8:11, giving an entirely new context to Jesus’ words.

“Let him who is without sin cast the First Stone.” And Jesus also said, “Go and sin no more.”

Sweat pushed out of the pores of my palm, which still rested on the top of the stack of papers. I could only remember parts of conversations that Stephen Black had had with me. These short audio recordings would constantly run through my head, such as the time that Black told me that the normalization of same-sex relationships was a conspiracy created by Hollywood, specifically Ellen DeGeneres. The time I was told that since I was wanting to have sex with other men, I was committing an act equivalent to incest, bestiality, or pedophilia. And I tried to sort through every conversation, seeing if there’s some key point that could lead me to figure out how long I was at FSM.

“It’s never too late to get saved. I mean look at me,” Stephen Black had said, pointing at himself.

“I am saved,” I said.

“Oh, no you aren’t. Not when you’ve had sexual contact with another man.”

“I never have.”

“Oh, don’t lie to me. Lying is a sin too. You simply wouldn’t be having these feelings if that were the case.” His tone was sharp, emphasizing the consonants that started a word, and at an aggressive volume. “It’s best to come clean, so we can help you. Right now, you’ve chosen Hell. When you choose the gay lifestyle, there’s only two things that come out of that: rape and AID’s.”

During therapy, he would continue blaming other forms of sexual interaction. At first, I must’ve experimented with another boy and it stuck. Then, I was told I must’ve not been showed affection by my father. The narratives that Black applied to me kept getting stranger and stranger, further from the actual truth: that I was a normal boy raised in a small Oklahoma town who routinely attended a Mennonite church. I must’ve been molested as a child. A perverted uncle? My own father? When I would tell Black that I had never had sexual contact with anyone, it was met with retaliation, mostly coming in the form of an angry tone. I couldn’t find any hints to answer my question, only understanding how reparative therapy affected me in the long run. His words would contribute to my inability to keep a long-term relationship, my struggle with depression and swinging moods.

During one conversation we had, he explained to me that he was openly gay in the 1980’s and was ultimately rejected by the LGBT community. One online article, printed out and laying among the stack of papers on the countertop, said that this was due to his inability to control his weight. “I watched all the friends I had die of AID’s,” he had told me. “Had a couple of boyfriends. None of them went anywhere. Now that I think of it, being molested as a child caused sexual confusion in my life. It only got worse when I was raped two times after that. I was completely lost. And then my friend invited me to her family’s home. I went and, they were Christians, and I just felt the love that they had for God just bounce off the walls of this home. And I told them that I wanted to love God the way they do and, when my friend was driving me home, she asked me if I was going to stop being gay since I had accepted Jesus Christ into my soul. That’s when I knew that what I had been doing was wrong. It was a sexual sin and a death sentence. I should have known this when I was a teenager and was watching all my friends around me die of AID’s. It was a punishment from God. I was that blind. I couldn’t put two and two together.” When he talked to me about this point in his life, he stuttered a little, looking at me with his pale brown iris’ that pushed down onto his sagging eyelids. He had three children and a wife at this point in his life; a model for every person that attended FSM, struggling with homosexuality. I wondered if he still had gay thoughts. I wondered if he stared at the shirtless men pictured on the underwear boxes in department stores, observing the tight fit that outlined the model’s bulge. I wondered if he used a pill to get it up for his wife, if he had created some false version of himself to fulfill his desire to be a straight man. Even though, at the same time, I also wanted to be very straight. And this desire to be straight, to become masculine, was only achievable by giving up things that Black said made me gay: sexual interactions, a disconnected relationship with a family member, art, and literature.

“What subject are you best at?” Black asked me.

“English.”

“And what do you read in English?”

“Romeo and Juliet. The Invisible Man.“

“Who’s your favorite author?”

“Truman Capote.”

He shook his head, looking back at my mother, who was sitting next to me. “Oh, dear God. Is English the class he’s most prolific in?”

“Yes.”

“Then your son’s behavior is probably worse than you thought. They’re teaching him novels, plays, that are built on the foundation of sexually immoral actions. Do you know what he writes in English class?”

“No,” she said.

He looked at me.

“What do you write in English?”

“Just essays.”

He looked back at my mother. “You might want to read what’s in those essays he’s writing. It might be very revealing of what’s happening to him.”

I didn’t read for two years after conversion therapy, after my love for Harper Lee and Truman Capote was connected to my thoughts about other men. I remember my junior year of High School, lying to my teacher, telling her I had read Beowulf and The Taming of the Shrew, trying to hide the fact that I was told that this literature would make me commit acts that would send me straight to Hell.

I stopped staring at the cluttered table, feeling emotionally drained. Snow had piled up outside and the intensity of the bright white glare from the ground faded the reflection of Trump from the television. A pile of snow covered the dead flowers in the garden, making only their outlining shapes visible. My squinting eyes tried to see what was happening on the television screen from just the reflection in the window, but I quit when I told myself to avoid the politics on the screen. I took the remote and turned off the debate over the looming government shutdown. Literature was on my mind. The hallway was narrow and I ran my hand across the knock down finish wall, every texture pushing itself against my fingertips, wanting to be felt. I turned around the corner, grasping the side of the wooden frame. My bedroom. My eyes opened wide as I stopped, looking at the books that lined up on my windowsill, stacked on top of my dresser, and filled two bookcases.

My hand ran across the shelves as I read the names of authors that wrote the books that I had been told were demonic. To Kill a Mockingbird. The Crucible. The Portrait of Dorian Gray. My hand stopped at a name that I hadn’t read in years and I sighed when I whispered it to myself. “Capote”.

“Capote?” Stephen Black said to me once. “You can’t read gay authors. You don’t know how those words corrupt the human soul. And he’s the worst. He was extremely anti-Christian and he showed it in his actions.”

These words held me back so much. I had tossed my copy of In Cold Blood into the trash, years ago, because I was afraid it would make me have same-sex attractions.

I repeated the name on the book’s spine, “Capote,” picked it up, reading the title on the front cover. Other Rooms, Other Voices. Opening the pages, I smelt that dusty scent from years of neglect. In my palm, I could feel the worn spine. It was ripped at the bottom and the cream-colored cover was replaced by the white paper underneath. A tear ran up along with ripples that reached towards the room’s popcorn ceiling. These permanent marks of damage, of course, were all caused from those hard years when nothing was preserved.

Author

CHARLES JONES is a fiction and creative nonfiction writer. His work has previously been published in The Gold Mine and The Rose. He is currently pursuing a BA in English at Cameron University. He lives in Lawton, Oklahoma, with his dog, Winston.

CHARLES JONES is a fiction and creative nonfiction writer. His work has previously been published in The Gold Mine and The Rose. He is currently pursuing a BA in English at Cameron University. He lives in Lawton, Oklahoma, with his dog, Winston.

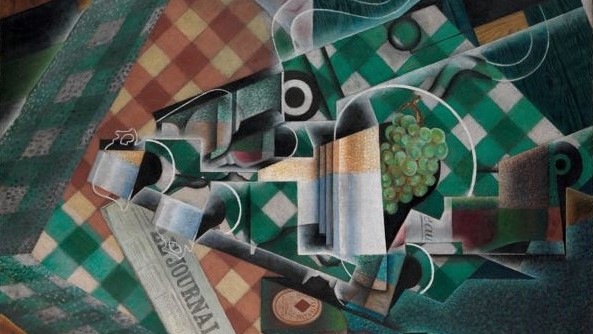

Featured image: Juan Gris, “Still Life with Checked Tablecloth,” oil and graphite on canvas, 1915, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.