No more hard fruitcake encased in brittle icing. The world was changing, and the bride wanted a moist sponge cake with tart lemon curd, its tiers swept over with buttercream frosting. Online descriptions of the royal cake elicited in me feelings of lightness and joy, and I decided that watching the wedding of England’s Prince Harry and biracial American Meghan Markle could be a release, a visual experience to take away pains of the past. My husband of twenty-seven years declined the invitation in favor of pursuing one of his weekend projects—specifically, rigging up a chain at the corner of his backyard workshop to guide rain water from the gutter down into a large ceramic pot.

But our younger daughter, just home for the summer, did want to watch with me, so I drove to the organic bakery to select plump madeleines for the television event. To view the live broadcast in Tennessee, we set our alarms for six a.m. that Saturday morning.

I witnessed the mother of the royal bride step out of a Rolls Royce in front of St. George’s Chapel, her rich, brown skin even more a proclamation of change than the planned cake. That warm, reddish brown was the same nutmeg skin color of the boy I’d fallen in love with when I was a girl of eighteen.

Like Ms. Markle’s mother, he had bright eyes that crinkled when he smiled. With a striking appearance and interesting thoughts about culture, science, and the nature of time, he played drums in a punk rock band on campus. For months, I submersed myself in him, his strong musky smell, his soft kisses, his gentle low voice. He’d grown up with a German mother and an African American father, moving around Germany and the States, attending ten schools in twelve years, including a stint in Augusta, Georgia, where his parents’ marriage was at that time illegal. I held his story—and the expression of his story, which was him, his intricate self, his lean, young body.

And he also held me, my tall, anxious, brainy, white self. Before I met him, I’d been a perfectionist at an all-girls prep school on the East Coast. At night doing homework, I’d worried I’d never find love. But at college in California, I soaked in the sunshine and the wide expanse of my new world, opening myself to ideas, experiences, and the embrace of this complex and beautiful person. Under a featherbed covered in a pattern of wildflowers, we lay for whole days in his narrow twin bed, entwined. It was a deep, nurturing love, free of shame.

“You’ve dropped a bomb on the family,” my father called to say.

The words tore through me. They were aggressive, destroying the sweet reality I was experiencing. I twisted the rubber phone cord around my hand and began to steel myself against my parents.

Now I wanted to partake of the television event on the terms we all enjoy weddings: the dress, the vows, the flowers, the cake. With my younger daughter at home—the one into fashion, design, and Prince Harry—who better to ooh and ahh with?

And we did ooh and aah. We brought the bakery box downstairs, wrapped ourselves in blankets on the couch and took bites of lemony, iced madeleines as we watched. The images on our big screen were lovely—the simple gown, the silk tulle veil with its sunlit train, the groom’s frockcoat uniform—so much beauty, all of it heightened by the majestic light of the medieval chapel.

This college-aged daughter, who looks a bit like Ms. Markle, sat with her knees pulled to her chest, cocooned in fleece, smiling. She was taken by the singing, and when the camera cut to Prince Harry rubbing the bride’s hand with his thumb, she blurted out, “Oh my God, they’re everything!” She couldn’t get over the sweetness of their holding hands throughout. During the long televised carriage ride, she was gripped by the crowd’s jubilation and the newlyweds’ whispers to each other.

I also fell under a spell, one swirling with my experience. I was struck by how these two people were pushing and expanding the strict boundaries of tradition—of what was put forth and sanctioned by the British monarchy. Prince Harry and Ms. Markle put blackness in the spotlight at the royal wedding when, with the bride’s features and light skin, it would have been far easier and more likely for her to sidestep it.

I was moved when the first African American head of the Episcopal Church gave the sermon in the oratorical tradition of black preachers about the power of love to liberate, to change the world. I found it bold when he spoke with passion to this particular assemblage in finery and fascinators about the spiritual lives of formerly enslaved Americans.

But it was the gospel choir’s performance of the civil rights anthem “Stand by Me” that cracked me open. Those words—if the sky that we look upon should tumble and fall and the mountain should crumble to the sea, I won’t cry, I won’t cry, no I won’t shed a tear just as long as you stand, stand by me—those words echoing through the towering space, emanating from the voices of black Brits from South London, softened my defended heart. I could see that, while Prince Harry and Ms. Markle enjoyed the height of privilege, they were also brave, in their lives and in their choices, and I applauded them.

I recalled and acknowledged my own courage. I eventually did stand up for my inner life, for what I believed, in order to marry and create a family with the young man I’d dated for a tough decade. I broke through brittleness and meanness to stand by a black man whom I loved and who loved me.

“You’ve dropped a bomb on the family.”

The words were wielded unfairly. Not only was my father a student of history and wars, but he flew jet fighters and patrol bombers in the Navy. He understood the meaning and devastation of bombs. These words and other harsh words reverberated in me. I felt ashamed and invisible, withering from parental, familial, and subtle societal disapproval. I came to think I was dying.

To outlast a Romeo and Juliet story of doomed love required I stand firm in the world, the real world with its history of division and discrimination. I needed courage.

In the lamplight of my studio apartment in California, I sat by myself on the cheap carpet one evening and dialed my parents’ home across the country. I concentrated intently on the information I needed to convey, on the passing of it from me to them.

“We’ve decided to get married,” I said into the receiver. “The wedding is June twenty-second. We’d love you to come.”

Silence. And then my father made his wise and kind pronouncement: “We’ll be there.”

Even my mother, the harshest and most unyielding of all in her disapproval of the relationship, called back the next morning to express tentative excitement about the selection of a dress.

We were married in a small California sanctuary, a round chapel built of cedar where the sun’s rays peeked through the feathery Eucalyptus leaves and down through the skylights to shine on us. In the side room, before the ceremony, I became faint, my three bridesmaids fanning me, reminding me to breathe. In and out I breathed, feeling an overwhelming sensation of swallowing my life whole. As the music “Joy of Man’s Desiring” sounded through the organ’s steel pipes, I stood slender and tall in my lace dress, a headpiece of pearldrops decorating my forehead. My handsome groom stood waiting for me at the altar. I felt cherished as he, with a confident posture and quiet smile, received me.

From the couch where I sat watching the royal wedding, I could see him in the yard, busy with his workshop project. He’s more accomplished now—husband, father, professor—a doer who likes to bring ideas to fruition. When I asked him why he was making the rain chain, he said it’d be more fun than having a traditional downspout—more interesting to watch the rain find its way down along the chain.

With support, societal change, and plenty of luck, we managed to build a life together—move to Tennessee, raise our biracial daughters, and create a home and community for us and for them. What I want for the girls is something like what I have come to enjoy, a path that flows with companionship, warmth.

We finished watching the commentary and replays, finally standing up in our pajamas to turn off the TV. I knew the marriage of a member of the British royal family to a biracial American held meaning for our daughter, and I also knew not to pry. A sensitive, intricate young woman with a potentially treacherous racial path of her own to navigate, she needs space and quiet support. I have watched both our daughters at times steel themselves against the pricks, barbs, and injustice of racism. I don’t want them to become hardened. I want them to develop courage, follow their hearts, hold steady and firm.

The chain at the corner of my husband’s workshop will serve as a loose guide for the rain water, slowing it down, encouraging it to coalesce and find varying paths to the landing place. The shape and structure of the chain will honor the properties of water, supporting its inexact journey. We too will continue to find our imperfect way along the chain—like trickles of water, sputtering, seeking, merging—part of a stream before us and also after us.

JENNIFER BOSTWICK OWENS holds degrees in English from Stanford University and Mills College and has had pieces published by StyleBlueprint, Mothering and SheKnows. In Nashville, she serves as a writing coach for graduate students at Vanderbilt and is an active member of the Porch Writers’ Collective.

JENNIFER BOSTWICK OWENS holds degrees in English from Stanford University and Mills College and has had pieces published by StyleBlueprint, Mothering and SheKnows. In Nashville, she serves as a writing coach for graduate students at Vanderbilt and is an active member of the Porch Writers’ Collective.

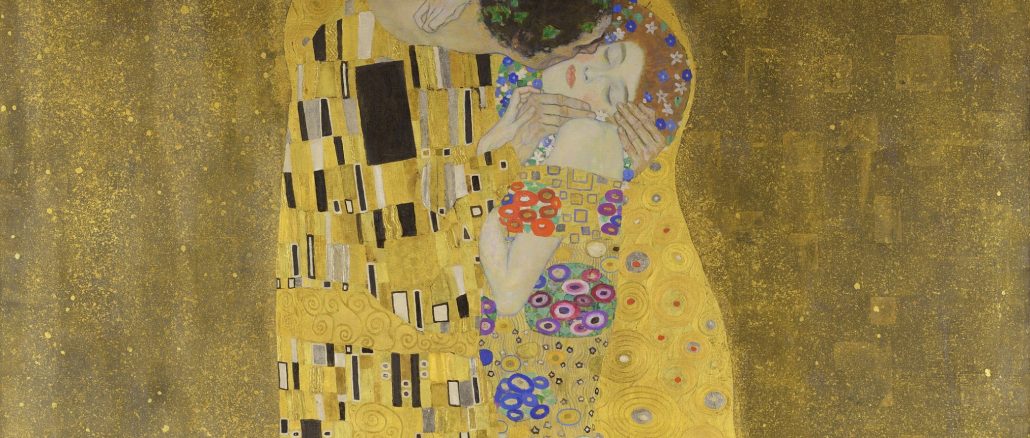

Featured image: Gustav Klimt, “The Kiss,” painting, 1907-1908, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere Museum.