Conversation with misfit turned journalist Adriaan Alsema of Colombia Reports about being a foreign correspondent, the roots of Colombia’s armed conflict, the role of journalism, and what humbles him about the land of El Dorado.

“Do you want to know the truth about the truth?

Do you want to know the future of our youth?

Well, I could tell you, but you’ve got to have the time.

You’ve got to listen, you’ve got to open up your mind…

Clarity is all you need, it’s all you need.

Clarity is all you need, it’s all you need.”

– from “Death Funk,” by Doctor Love and His Imaginary Band –

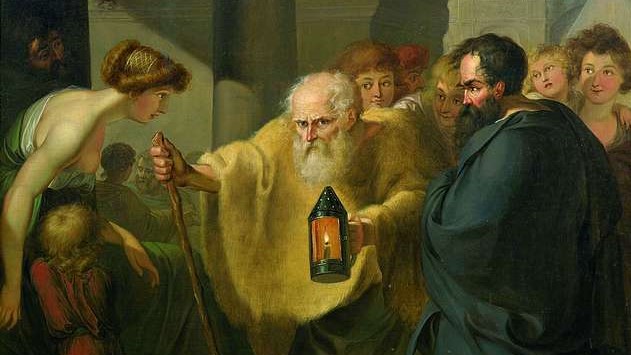

Over the course of our near decade-long friendship, ADRIAAN ALSEMA has compared himself to Diogenes, the founder of Cynic philosophy. The very same who Plato referred to as a “Socrates gone mad.” I don’t know if Alsema would consider himself a cynic of the ancient variety, but there is something about his character that taps along with its beat—pissing on political bonfires and spitting on the faces of power in the process.

This goes far beyond his role as founder and editor-in-chief of Colombia Reports and as a journalist in search of mental clarity, lucidity, and freedom from the smoke of faith and fake news. His do-it-yourself, punk, anti-institution personality and critiques of conventions have made him both a controversial figure and a man with a growing cult following.

He is his own man; yet, he is fully devoted to his craft and reliant on his community.

There’s something ridiculous, almost satirical, about being deemed controversial as a journalist for placing a magnifying glass on society because you value facts and evidence over blind acceptance…because you deface traditional desires of wealth, power, and fame.

As a journalist, Alsema has tried to unpack and dissect the frameworks of Colombian society—those lenses that pass as common sense. He has also shined a lantern on the roots of Colombian consciousness—its backdrop, social structures, agents, institutions, unspoken assumptions, and taken-for-granted ideologies. He does all this independent of hidden interests.

I have yet to meet a journalist more transparent, authentic, honest, and willing to sacrifice himself for the sake of informing, empowering, and being the voice of his community. In doing so, with his unconventional manner of running a news organization, he has informed his readers in ways most others, especially in Colombia, simply cannot.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Julián Esteban Torres López: You are the founder and editor-in-chief of Colombia Reports, the country’s largest independent news source in English. However, becoming a journalist in Colombia wasn’t your first dream while growing up and living in the Netherlands. You consider yourself a misfit turned journalist. Let’s start there. Who is Adriaan Alsema, the misfit?

Adriaan Alsema: The misfit is the juvenile delinquent who gave the middle finger to high school at 16, hoping to become a rock star, but ended up working as a garbage collector, cleaning lady, and janitor instead. It wasn’t until later, through the janitor job at a radio station, that I got interested in journalism.

JETL: Who is Adriaan Alsema, the musician?

AA: There is no Adriaan Alsema, the musician. You’re confusing me with Doctor Love and His Imaginary Band, probably because at one point Doctor Love was a member of Adriaan Alsema and the Good-Looking Intellectuals.

JETL: What is The Irrational Library and what is your connection to it?

AA: According to the Chamber of Commerce in the Netherlands, the Irrational Library is a second-hand shop run by Joshua Baumgarten, an American guy, also known as Johnny The Jewboy Bumfucker and Mr. Weirdbeard. He has been the driving force behind the artist collective that has been promoting Dutch counterculture and is the lead “singer” in the band called The Irrational Library.

Joshua and I met ages ago. I don’t remember exactly when because it was during my drinking period, I just remember he worked as a bartender and I called him “the fucking American.” We’ve been friends since. He’s one of the finest men I have ever known.

JETL: What is Colombia Reports to you and who is Adriaan Alsema, enfant terrible-in-chief of Colombia Reports?

AA: Colombia Reports is a news website. In fact, it’s the largest news website in English on Colombia. It’s also my baby. I founded it and initially was the “editor-in-chief.”

What happened was that the page grew very big and influential and I found out that people were taking me far too seriously, that I was becoming an “authority,” so I changed my official title to “enfant terrible-in-chief,” just so that people would be forced to think for themselves and not be fooled by pretentious titles.

JETL: Why Colombia? What’s your relationship with Colombia? What continues to draw you to it? What pushes you away from the Netherlands?

AA: The Netherlands is a lovely country, but it’s so goddamn sophisticated that it’s become dull. The country’s also gotten so rich that the general culture is very protective, people are afraid to lose their riches and privileges. I ended up first in Colombia in 2005 because my drummer landed a teaching job here and she invited me over. I fell in love immediately, because it’s a cultural treasure trove and has palm trees. Moreover, there exists a culture, or a subculture rather, that stimulates people to work towards a better future.

I got kicked out of the country last year and was forced to spend some nine months in the Netherlands again, only to find out I fit in even less than I did before. Everything has become gentrified, everything is orderly. It was a miserable time. Being a journalist in Colombia isn’t easy, like, it’s easy to create a lot of enemies. But it is also a place where journalists have purpose, where I can make myself useful. Colombians have become my people and I will take a bullet for them.

JETL: When you moved to Colombia you had very limited Spanish. How did you pick up the language?

AA: I made friends with a few street artists and particularly rappers, who taught me the basics of the language and the most important curse words. Because my work is all about language, I was pretty much forced to pick up on the rest relatively quickly. Fortunately, in the Netherlands kids are taught at least three languages in middle school, so the skill of learning I had picked up when young in Europe already.

JETL: You’ve been quoted as stating “that running a news website almost automatically creates conflicts with the economic interests of investors.” You’re quite adamant about Colombia Reports remaining independent and not being affiliated with any political or social organization. Where does this attitude come from? How did you land on that perspective?

AA: The purpose of journalism is to inform people about what is happening with their society, how their taxes are spent, which policies work, etc. I believe this means that journalists’ allegiance must lie with their community, and nothing else. Commercial interests compromise this in principle, because the purpose of advertisers or commercial stakeholders is different.

I don’t believe this corruption of loyalty is done in bad faith, but I do feel that the conflicting interests of commercial journalism, like having to make a profit, can only lead to corruption.

This approach is often seen as opposition to political organizations or dogmas, like anti-capitalist, which in effect is true, I suppose. But this is because journalism is about checking on the economic, social, and political forces in power, not because journalists favor what would be the opposite or the alternative.

In Colombia, we were pissing on the liberals’ bonfire until the conservatives took power in August, and now we piss on their bonfire. I can’t wait for the socialists to assume power, because I haven’t been able to piss on their bonfire for ages.

JETL: You say you’re a lover of DIY ethics. What do you mean by that?

AA: Do It Yourself ethics allow people to do something if they think something is shit and believe they can do it better. It’s a punk thing, really. If you don’t like the garbage on the radio, you learn five chords on the guitar, get your girlfriend to dump you, and write a song about it. And if you’re good at it, you may even become successful in whatever you do.

In the case of journalism, I thought the newspaper I worked for was shit so I started my own, just without bullshit like marketing and sales and all. I started at the bottom and learned the whole process auto-didactically. Now I can weld broken cables, point out the similarities between Mussolini’s economic policy and that of Colombia’s president Ivan Duque, and I can write 300 words in a second language in 15 minutes without saying “fuck” once.

JETL: What are your political leanings?

AA: I call myself an anarchist, just to freak people out. I’m a journalist, I know better than to fall for political dogmas, or worse, vote for one.

JETL: Dozens of budding journalists have acquired their initial industry experience via Colombia Reports. What’s your training and journalism philosophy? How do you mold them into quality journalists? What makes a good journalist?

AA: A good journalist will serve and defend his community. If you’re an American journalist writing for an American community, your allegiance must lie with that community. Also, a journalist must never forget that, especially online, he must be competitive with porn. So, an article about next year’s budget deficits must compete with and defeat an attractive pair of tits.

A good journalist knows to inform his community, empower his community, and be the voice of a community. If a community is divided, as it always would be, the journalist must indicate where common ground could be found, and contribute to the comprehension for the convictions on the other side of the divide.

JETL: Colombia Reports recently celebrated its ten-year anniversary. As you look back over the decade, what Colombian stories stand out the most?

AA: Individual stories are not important, it’s about the body of work, the consistent and reliable service you provide as a journalist to your community. A big part of my body of work is unknown, because the context is only coming out now that there are transitional justice systems and a Truth Commission. Everybody outside Colombia knows about the country’s guerrillas, groups like the FARC, etc. Now, these guerrillas only committed 17% of the civilian killings during the conflict, so why don’t people know who killed the 83%? How did that happen? And why? This is the “story” that is only just being investigated.

JETL: Colombia is one of the most important countries for U.S. foreign policy in Latin America, yet you noticed that very little information was available to English speakers who didn’t also read or speak Spanish. You founded Colombia Reports with this in mind. What bits of information or data do you wish more people outside (and even inside) of Colombia knew about the country?

AA: I never had this in mind, but learned this along the way. For the sake of the lives of all, we must stop the drug war, we must remove the violence from the drug problem. Colombia is producing 12 times more cocaine than when Pablo Escobar was “king.” Tens of thousands of people have died. People continue to die because of drug overdoses in numbers that don’t have to be this high. We must carefully and wisely regulate drug consumption, this goes for cocaine as much as for painkillers.

JETL: What myths, lies, or fake news about Colombia do you wish died?

AA: Did you know that George W. Bush awarded a medal of freedom to a former Medellin Cartel associate?

JETL: How would you describe Colombia’s socio-political situation?

AA: Neo-feudalism or fascist corporatism.

JETL: What are the roots of Colombia’s armed conflict, in your opinion?

AA: Unlike the English colonization of northern America, in which indentured servants were granted a piece of land (and a stake in the colony), Spanish colonization only divided land patronage and political power to those of Spanish descent while the Spanish King was ultimately the supreme ruler of all. When the revolution came and Spanish rule ended, only the king’s influence was removed. Land ownership and political control remained with the elite. This has been a cause of conflict in Colombia, as well as Venezuela and Peru, and continues to be a major fuel for conflict and violence in Colombia.

JETL: You’re a data and statistics nerd and enjoy security and risk analysis. What statistics about Colombia humble you? What data should we all know? In terms of security and risk, what should foreign travelers and businesses be aware of?

AA: The statistic that humbles me is that we have had like 12 or 13 civil wars in 200 years, which makes a 14th war hardly a far-fetched possibility.

Foreign travelers shouldn’t worry and just enjoy the beauties of Colombian culture and nature, our domestic issues shouldn’t be of their concern. Businesses should be aware that this is not a free market economy, but, as I indicated earlier, a cartelized economic system controlled by a traditional elite and a relatively new narco-elite. It’s easy to confuse a legitimate businessman with a mafia boss, which is where many foreign businesses burnt their fingers.

JETL: What is the current situation for foreign journalists in Colombia?

AA: It’s the worst I have seen in the past 10 years. I’m not even sure if I will still have a visa after November 30. More than 12 foreign correspondents either lost or are at risk of losing their visa.

JETL: Are there different risks for domestic journalists in comparison to foreign journalists in Colombia?

AA: Two of our Colombian and three of our Ecuadorean colleagues have been murdered so far this year. Death threats are more common than ever. Journalists’ lives are ruined because they are forced to live in safe houses or spend their lives with bodyguards. Others live with the constant fear that death can await them around every corner.

JETL: You were recently deported from Colombia but are back now. What happened?

AA: I screwed up my visa years ago, but wanted to finish reporting on the peace talks that took place between 2012 and 2016. Documenting this process was a once in a lifetime opportunity for me as a journalist, it is the body of work I am most proud of. When the process was over and I reported myself to the migration authority, I was justly deported. When I was allowed back in 10 months later, I brought the lady who deported me Dutch cookies, because she was so nice.

JETL: Do you consider yourself an expat or an immigrant?

AA: A migrant, or world citizen as Diogenes would call it.

JETL: What are the three most dire situations for Colombia, in your opinion?

AA: 1. The country’s corrupt and weak state system enables criminal structures of all kinds to assume power and fails to assume the duties and responsibilities that belong to a state. In my opinion, Colombia, like Venezuela, are perfect examples of failed states.

2. The armed conflict has shred the country’s social fabric to pieces. I don’t recognize the sense of community or belonging that I see in other countries. Worst of this is that this doesn’t just show on the street, but also inside people’s homes. Domestic violence levels are extremely high, particularly in families that have been most affected by the armed conflict.

3. Social exclusion and a lack of social mobility is spurring criminal activity and degrading women. More than half of the women in my city are sex workers or have engaged in prostitution, as their only means to get by and feed their families. Men often have no other option than to join criminal organizations. I would’ve done the same thing had it not been for my privileged situation. There is no dignity in starvation.

JETL: What do you think have been the biggest mistakes the Colombian government, the paramilitaries, the guerrillas, Colombian media, the international community, and Colombian people have made over the years?

AA: There is no one answer to this question, so allow me to stick to the government, which insists on ignoring the core problem of the country, which is a break from its colonial past and the creation of a democratic state system. The failure to do so is what generates guerrillas, self-defense groups, criminal organizations, and violence.

JETL: Over the years, you have been hopeful about the situation in Colombia, but there have also been times when you were scared and lost hope. Can you elaborate on those moments?

AA: I have never lost hope, but obviously I am scared. The most powerful politician in Colombia, former President Alvaro Uribe, is a former Medellin Cartel associate with fascist tendencies. The guy has left millions of victims. Notwithstanding there are still people who adore him, who support a mafia-like state as if it were Colombian political culture, which it isn’t. Until we are able to become a society that rejects rather than admires strongmen, we are all at risk, especially those who think differently, are members of minority groups, or express criticism. I am scared right now. I have honorably worked for a decade to create a news website that I believe is honest and serves the benefit of the people. Yet the chances are that everything I have, my belongings, my friends, my home, are taken away from me.

JETL: What is the worst advice you see or hear being dispensed in your world?

AA: “Don’t do that.”

JETL: As a journalist, what’s more important to you: accuracy, a balance of points of view, or objectivity? Why?

AA: Objectivity only exists in theory. If I talk to a war victim, as a human being I will be concerned about his or her well-being. As a journalist in Colombia I have also found myself being the object, because I am harassed by the government or because colleagues or sources are murdered.

Therefore, accuracy, independence of thought, and an appropriately as possible context are values I pursue, that and the active disruption of inaccurate or fictitious/propaganda narratives.

JETL: What have you changed your mind about in the last few years? Why?

AA: The increased use of disinformation and lies is forcing me to counter false narratives and propaganda more aggressively. Also, the more self-sufficient I have become as a journalist, the more I can experiment with style and move away from the AP style guide. Ultimately, I have been trying to use more cheeky headlines or intros to draw people’s attention to complex subjects that, if written in AP Style, wouldn’t be read by anyone.

JETL: Unlike many newspaper editors-in-chief/enfants terrible-in-chief, you are very much directly engaged with your readers. All one has to do is read through the comment section of any article you post on your Colombia Reports Facebook page. You respond to almost every (if not every) comment and continue the dialogue there. How do you manage responding to the community vs. creating content for the website? Do you see the Facebook page as a direct extension of the site, given your philosophy that journalists exist to serve their communities? Also, how do you respond to critics, trolls, haters, etc.?

AA: My job is to contribute to a fact-based debate, and the search for middle ground in the case of division. I kick off such debate by publishing an article, but feel that by engaging in the debate I can avoid escalations and promote civilized dialogue. Assuming an active role as moderator appears to allow moderates to speak up more often while being protected from harassment, and change the general rhetoric to one that is more comprehensive and inclusive.

In the case of trolls, this means telling them to go fuck themselves once every so often. In the case of haters, I have an army of engaged readers who will immediately engage if I am subject to abuse.

JETL: Do you receive hate mail?

AA: Tons. They are often the cherry on the pie. I generally send them hate mail back, or if someone is trying to intimidate or threaten me I give them my home address, tell them to put on their MAGA hat and try to reach my front door in downtown Medellin without being lynched by a mob.

JETL: The audience of Colombia Reports tends to be English speakers, for obvious reasons. What’s your interaction like with your Spanish-speaking Colombian community?

AA: Ultimately, I have found that I am also reaching young Colombian students, mainly public education students, I assume. I am dead chuffed by that, because it means I am now apparently able to inform Spanish speakers (who often use Google translator or anything), and I am reaching a younger and local generation without resorting to slang I am too old for.

JETL: What topic would you speak about if you were asked to give a TED Talk on something outside of your main area of expertise?

AA: Fuck off. TED Talks are for self-absorbed wankers. It’s marketing, and I piss on marketing.

JETL: Your authenticity and honesty are qualities I’ve found refreshing about you, especially as a journalist. Have these qualities, however, ever been a hindrance to your reporting? For example, I remember being in the same room as you once, and another Colombian news source called you because it wanted to interview you or ask you for a quote. When they stated who they were, you mentioned something along the lines of, I know who you are and I hate you. (I’m paraphrasing.) Has your directness and bluntness gotten you in trouble in your field?

AA: [Laughs out loud] All the fucking time, but I’m a punk like that. I like kicking against the pricks.

JETL: What obsessions do you explore when you’re not working on Colombia Reports?

AA: I like writing songs and recently did my first poem in ages. I also like getting fucked up on drugs and get naked with a bunch of women.

JETL: What is something that mainstream Colombian news sources lack that Colombia Reports offers?

AA: Honesty and I have no criminal record.

JETL: What is something you believe in that other people think is insane?

AA: I believe in the necessity to gradually abolish all forms of power and authority and the creation of grass-roots communities that function independent or autonomous from mainstream society and free from government.

JETL: If you had the funding, what would you like to do with Colombia Reports? Where would you like to see it be five to 10 years from now?

AA: As a proper hypocrite, I am requesting a grant from the Dutch government to duplicate my anarchist experiment in Spanish.

JETL: How do you currently fund Colombia Reports?

AA: Half is funded by Google Ads, my work is syndicated by Dow Jones and BBC Monitoring, which gets me a few tenners a month, but mainly I want to be funded voluntarily by the people in my audience who can afford it.

JETL: How can others support Colombia Reports?

AA: By becoming a patron or a member of the editorial board, or by submitting content.

JETL: What is your favorite thing about Colombia and your life there?

AA: My favorite thing about Colombia is the variety of cultures. The country’s different indigenous groups have enriched me with wisdom, the black minority has given me some of the most beautiful music I have ever heard, and the underground scene in Medellin has taught me how to be resilient and remain strong in the face of adversity. Colombia has made me a better person, a wiser man, and has given me the capacity to be sympathetic to opposing viewpoints.

Julián Esteban Torres López is a Colombian-born journalist, researcher, writer, and editor. Before founding The Nasiona, he ran several cultural and arts organizations, edited journals and books, was a social justice and public history researcher, wrote a column for Colombia Reports, taught university courses, and managed a history museum. He’s a Pushcart Prize nominee and 1st place winner of the Rudy Dusek Essay Prize in Philosophy of Art. His book Marx’s Humanism and Its Limits was BookAuthority’s Best New Socialism Book of 2018. His micro-poetry collection Ninety-Two Surgically Enhanced Mannequins is not as serious in tone as his forthcoming book Reporting on Colombia: Essays on Colombia’s History, Culture, Peoples, and Armed Conflict.

Twitter: je_torres_lopez

Featured image: Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, “Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man,” oil on panel, ca. 1780.