The personal essay is an exposé on loss and absence. Tolu Daniel explores how the most random events influence each other.

It should rain. But for some reason the rain is shy and from my window I can see people carrying umbrellas as though pre-empting it. I planned to stay in my house all day because, like the rain, I wasn’t much in the mood for company. It was another anniversary of my brother-in-law’s death and the emotions from the morning he died were waking from their sleep, refusing to be subdued despite the years since. Over the last few years I have tucked the emotions into my subconscious, hoping never to encounter them but recently I have felt betrayed by time as the moments emerge from where they have been kept, overlapping into the present. There is a lie we tell ourselves about how the passage of time heals wounds of absence but I know better now. I know the wounds will come undone at every anniversary, at every remembrance, at every instance when conversation gets to him. His death broke me in many ways but it was my not knowing how to express the grief that held my neck down for slaughter. The months after he died, I watched everyone around me, their heads between their legs, their shoulders shaking, tears flowing. I asked my brother what he thought could be wrong with me since it seemed like I wouldn’t be shedding my share of the tears. He could only answer me with silence. I am jealous of him, jealous of his ability to express his own grief in his own way.

It wasn’t as easy for me. I would spend more time obsessing with how others were coping, in a way this was how I grieved. But the thing about such kinds of grief is how it makes you forget who you are, what you are and who you have sworn to become. I had been moping for most of the day, refusing to leave my bed. This was until hunger tricked me into taking a walk in search of something to snack on.

It was evening. I figured most folks would have returned from work and my chances of meeting people who wanted to make small talk would be reduced. I set out, throwing a black three-quarter shorts and a t-shirt of the same colour on. Don’t they say black is the colour of grief? My legs felt heavy as I threw myself into the climb from the bed of the Ogun River Valley where my house was situated. The succour of the travelling evening breeze from the banks of the river caressing my face made the climb worth it. At the road, fatigue mated with a pressing need to return home. They laid their eggs on my chest and I wished at that moment I hadn’t left my house at all. The screeching sound of tyres on asphalt pierced through my earphones, adulterating the instrumentals to Adekunle Gold’s Ire which was playing. The buzz created by passing taxis threatened to crack the eggs that fatigue laid and homesickness fertilised.

A crowd became visible at the roundabout up ahead. The sight of so many people randomly standing was nauseating. The sight of young men like me, wearing white jalabiya and standing beside their fancy cars unsettled me. It made me muse about what I was doing with my life, I could join them to blame the government and our colonisers for everything that is wrong and take to crime like most of them.

A woman nestled where the descent back to the valley should begin, roasting corns for sale. I walked up to her, earphones plugged tightly into my ears to avoid conversing with strangers. I waited for the corn to roast. Other buyers joined the wait, standing with me, all of us united by our hunger for roasted corn. My phone battery signalled its approach to the end. I switched off the music playing on it but kept my ears plugged.

A woman arrived while the corn seller wrapped my corn. She had a turban-like headgear, a cream collared pink blouse, and a floor-length brownish sweeping skirt. She wanted corns of the same size as mine but wasn’t willing to pay more than the price I had paid. I expected the corn seller to rebuff her like a proper trader in Abeokuta would have.

“It’s not that cheap. If it was I would sell it to you,” she said. I was shocked by the softness in her voice. Traders here are angry by default. The woman wouldn’t back down. I felt like shutting her up, just for the purpose of re-establishing the peace that was before she arrived.

“Mama, I bought corns from here last year and the year before that. You should recognize me by now. I am no random passerby pricing your corn,” the woman argued.

The trader said it wasn’t her fault that corns were expensive this year. “Everything is expensive in the market.” I smiled thinking about how the woman’s insistence on getting a bargain for the stubs of corn reminded me of my mother. The woman must have mistaken the smile for a signal of support. She pulled at my earphones: “Ema binu o. How much did mama sell those corns to you?”

In that moment, I struggled to stop the vile emotions that coursed through my body. Aside from the woman’s banter with the trader she had touched me. She had the audacity to pull my earphones. I could have snapped. I could have yelled at her. But I didn’t. And it worked out somewhat.

My mother often told stories about how noisy a toddler I was whenever she wanted to embarrass me in front of my friends, how I would resist strangers who wanted to carry and play with me. As an adult, this was my ready excuse whenever I felt a foreign touch I wasn’t prepared for and my reaction caused a stir among my companions. I’d feel angry to the point of aggression. Late 2016 in the cusps of a depression during one of my two sessions with a therapist, I found that it had a name—haphephobia—and although mine wasn’t chronic, I was told it could become in time if not treated and treatment had come in the manner of exposure to foreign bodies on the random. So I thought I had been cured until this woman decided to touch me.

“Ask the vendor, please, and don’t touch me like that again,” I said, my face registering no animosity. The manner in which the words came out of my mouth shut the woman up.

The vendor mediated, dousing the sparks that would have ensued with some generosity and a lot of good prayers: “My daughter, take the corns at the price you want. You bought from me last year and the year before that, you’ll definitely come again next year. God will ensure our protection.”

The woman, who had lost her smile earlier at my instance, beamed with delight.

She said, “Amen.” Then, “Thank you.”

Returning home, finally freed from the unnecessary engagement, I pondered upon the final words of the vendor: The assurance of being in the same place, doing the same thing, the next year. It seemed like an abomination to my nomadic mind. But I couldn’t shake the possibility of it. I felt trapped by her words, by the certainty it carried, like a heavy load pressing down on its carrier. I wondered if my late brother-in-law, with the sureness and certainty with which he preached whenever he talked about God, was ever this sure about living beyond the time of his death.

***

The sky had become clouded while I dressed for work. I felt grateful for the coming rain although I knew it would cause me to be late for work. I wanted the relief the rain was supposed to bring with it. The heat of the preceding days and nights had squeezed out the little water the body had retained. I checked my phone—as was my way on most mornings—for news updates. The first headline that screamed at me was about the killings in Jos. Again. And now, Christian vigilantes hunted Muslims for reprisal. I dropped my phone, swung my backpack behind me, and proceeded to my place of work. It is 2018 and bad news is as common as the air we breathe.

The first taxi I hailed stopped, helping me to end the debate that was happening inside my head—of whether or not taxis in Abeokuta liked travelling towards my office during the morning rush hour traffic. The taxi driver was a man with a long face wrapped in his bushy beard. He wore his religion in his dressing.

“Assalamu Alaikum,” he said to me. I didn’t reply to his greeting even though it would have cost me nothing to. Instead, I stared at him as I took my seat beside him. He swung the little Nissan hatchback into motion. If he took offence at how I didn’t reply to his greeting, he didn’t show it. I had always wondered why people would casually throw religious greetings at strangers. But I have also learnt that validation is a hallmark of religion. This is why people go about with mirrors in search of people like them. With this driver, the familiar was the length of my trousers and the bushiness of my goatee. Although both of these things were deliberate, none had any religious connotation. The driver wouldn’t be the first to make this mistake.

By the time the taxi got to my stop, the rain was out and angry, drumming up a concert on the body of the taxi. The other passengers the taxi had picked up from their different locations had alighted. I was left alone with the driver. I was thinking about running from the vehicle to the nearest shed, projecting how wet I would get, when the driver told me in a gesture of kindness that I found shocking that he wouldn’t mind if I waited out the rain inside his car. I didn’t over-think it; I said thanks, reclined in my seat, and waited while the rain pounded the car on all sides.

“It is so difficult to be a successful taxi driver in this town,” the man began. I nodded my agreement. I assumed he was talking about the exorbitant levies the state government had heaped on them through the Internal Revenue Service. I asked him about it. He smiled and said, “We don’t pay those anymore, we Muslims.” He said those words as if they were supposed to mean something to me, as if I was supposed to solidarize with his cause. As if by some reason, I was supposed to be happy that we Muslims were getting ahead in this world where no one else was. But there lies the problem, I wasn’t a Muslim and I hadn’t been a Christian in a while either. I was still theorizing about the truthfulness of religion at the time but I wasn’t going to say that to him.

“We went to the governor and asked him to exclude us from the levy and he agreed. You know he is one of us, he had to prove it and he did.”I understood what he was saying, even though I didn’t know the details. I understood that in my country, religion was a weapon; it was something people leveraged on to get their ways. It was something people used to justify bad behaviour and horrible habits.”What I am saying is that the governor is supposed to fulfil his promise to put us in Arabic schools and pay us to learn the Quran so we can teach people the correct manner of serving God instead of wasting away delivering people to random locations.”

I wanted to ask why he thought whatever he was teaching would make the lives of people better. Or was he just saying this because he didn’t think being a taxi driver was dignifying enough? I even wanted to ask when the governor made the promise of enrolment into an Arabic school to him but I held myself back. And somehow, this man and the strange conversation I was having with him caused my mind to remember the many lessons on religion I took from my brother-in-law.

“Religion isn’t a creation of God, it is, however, an attempt to explain who God is by engaging in certain kinds of rituals, to keep us sane and pure till our time on this earth is up.”He was replying to an agnostic friend who had paid him a visit and had started the conversation about how pastors were profiting off the ignorance of their parishioners. I had expected him to rebuff the man or, in the very least, show him how ignorant his opinion was or defend his fellow pastors but he didn’t. I think I must have been fifteen at the time but Pastor Ben’s reply had bothered me and stolen sleep from my eyes. How could he have blasphemed with so much ease? But now, that reply has finally found a home in my head. Without religion, who are we?

When my brother-in-law was alive, he lived like a nomad; hopping through several European and Asian countries doing the work of the Lord. This was how he was mostly described: The Pastor. I remember wanting to be like him and in some instances wanting to be him because of the travel stories that rolled off his tongue in conversations. I remember the battle of wits that ensued when he was introduced to my dad as my sister’s fiancé; the manner of their conversation, his confidence, his audacity to keep up a conversation with my dad whom I believed to be the most knowledgeable person alive. This was what birthed my curiosity about him. This curiosity would stay potent till the day death took him from us.

***

I was still lost in my thoughts, thinking about my brother-in-law, when the rain rounded up. My eyes had become watery. The taxi driver tapped me, asking if everything was alright. When I regained my consciousness, I wanted to hate him for grabbing me like that. Then I remembered that he was only trying to be nice and made a mental note to deal with this irrational fear of body contact with strangers once and for all. I told him I was fine, reached for the door, and said my thanks. I ran to my office, the rain pricking my skin like a hundred needles dropping together to punish me for some crime I had committed: perhaps for the questions and thoughts swimming in the river that my head had become.

The weather was cold for most of the day. As I closed for the day, I thought about my brother-in-law again and wondered when that day would come when it would hurt less to think about him. I got back home around four in the afternoon. I was relieved to find the electricity on. I was about to touch the iron door, which led into my apartment when the electricity went out. I could hear the chorus of disappointed moans that accompanied the moment from my neighbours. With my shoulders drooped, I opened the door and was greeted by a river. My sitting room was flooded with water running from the open tap in the sink in the kitchen. The water was some inches short of my knees. I waddled through it to turn off the running tap. The water was warm as if a boiler had worked to keep it that way. It had not rained in my end of Abeokuta for a while even though other parts of the city were mostly wet. What this meant was that the well that doubled as a reservoir from which water was pumped into the building was dry. So when the rain from earlier filled the well, water was pumped into the house and my open tap had flooded my apartment with running water.

When the electricity was on, the water had climbed up to reach the extension boxes and submerged them. The water and the door must have been charged with electricity. If the power supply hadn’t been cut the moment before I touched the electrified metal door, I might have been fried. As I sat down to scoop the water off the floor and rearrange the house, my mind travelled back to the corn seller from the other day, it has been about three weeks to the encounter. Her prayer, the assurance it contained, and for a moment I wondered if the reason I had been saved from being fried was because an annoying woman once pulled at my earphones.

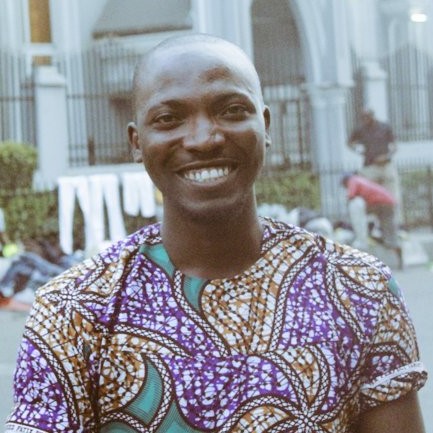

TOLU DANIEL Tolu Daniel is a writer and editor. His essays and short stories have appeared on Catapult, The Wagon Magazine, Prachya Review, Elsewhere Literary Journal, Expound Magazine, Bakwa Magazine, Saraba Magazine, Panorama Journal, Arts & Africa, and a few other places. Tolu currently holds editorial positions with Afridiaspora, The Single Story Foundation Journal, and Panorama Journal. He lives in Abeokuta, Nigeria, and can be found on Twitter via @iamToluDaniel.

TOLU DANIEL Tolu Daniel is a writer and editor. His essays and short stories have appeared on Catapult, The Wagon Magazine, Prachya Review, Elsewhere Literary Journal, Expound Magazine, Bakwa Magazine, Saraba Magazine, Panorama Journal, Arts & Africa, and a few other places. Tolu currently holds editorial positions with Afridiaspora, The Single Story Foundation Journal, and Panorama Journal. He lives in Abeokuta, Nigeria, and can be found on Twitter via @iamToluDaniel.

Featured image: Fancycrave, “Two Grilled Corn Cobs Beside Charcoal,” photograph, on Unsplash.