As memoir writers, we must enter the dark waters of memory where facts are few and remembered events are often unstable. But the subjective experience offers its own reality and can reveal the truths that facts can never discover.

Subjectivity. The Achilles heel of nonfiction writing. While journalists, historians, and other nonfiction writers wrestle with this human filter, always striving to avoid it, remove it, or at the very least minimize it, memoir embraces it. That is not to say the memoirist doesn’t have to uphold the unspoken contract of all nonfiction writers—to be honest, to find the relevant facts, and to reveal as much truth as possible. The memoirist simply works in murkier waters and that opacity itself becomes part of the storytelling.

When I first began writing seriously, it was an attempt to get to the facts of my childhood. I had a multitude of memories and too few facts. Born into the secrecy of fundamentalist Mormon polygamy, many of the records of my past had been falsified, obscuring the facts. My birth certificate was a fake, a false last name, a pretend father. I was taught to lie early on to protect my family from law enforcement and imprisonment. My mother told me that the lie was okay because it was protecting my father. I believed her because of the expression on her face when she saw a police cruiser parked outside our house or when she heard sirens in the distance, the way her mouth pinched tight and how she pulled hard on the cord that closed the blackout drapes at the windows. I learned that lies could protect, and the truth was dangerous. Always the lies were used to cover up reality. We were kept in the house and made to be quiet during school hours so the truancy of twenty school-age children would not be reported. Bank statements didn’t reflect the actual amount of money our family possessed. A marriage license showed that my father was legally married to only one woman, but he was married, in all the ways that mattered, to five others. When my sister was taken to the hospital for stitches, my mother couldn’t tell the truth, but could only decide what lie would be best to put on the paperwork.

On occasion when I found myself outside of the house, I had to be ready to pretend. “Where do you go to school honey?” a librarian once asked when I was checking out some books. I froze. I didn’t know what to say. I mumbled something and hurried out of the library leaving my books behind. When I was asked about how many brothers and sisters I had I always said twelve, thrilled to offer strangers a morsel of truth, a fact hidden inside of the larger fact: I actually had forty-five brothers and sisters but only twelve fully biological ones. I was warned never to tell anyone my father’s occupation, his name, or our last name. To this day, my mother goes by her false last name, chosen for its ordinariness, for its ability to camouflage. There were a few things I knew never to speak of even without being told: the constant physical abuse by my father’s third wife, the humiliations that stuck in the chest, like food in the esophagus, the inappropriate behavior of my brothers—and that of my own. The lies that protected us also made us most vulnerable. We were contained under a carefully constructed glass dome. All evidence was altered, silenced, or erased.

During my writing, I searched for proof of my life, but I found very little. Where were the facts? I pored through my old childhood diaries, but I had altered them in case someone found my notebook and read it. The truth had to be disguised. I had quite a few photos of my childhood, but photos don’t always tell the whole story. Images of smiling children arranged on a staircase, their bruised bodies hidden by long sleeved shirts and dresses that covered their legs; mothers who deeply distrusted one another, smiling and standing in a row, arms linked. It appeared normal. Pictures of toddlers in fat coats making snowballs on a winter day, a group of brothers shooting hoops with my father in the backyard and two sisters, heads leaned in close whispering, just turning at the sound of the camera clicking. According to the photos, we look the part of a happy family. A false impression.

They captured some valuable details. The color of the carpet in my father’s bedroom, the model of the station wagon parked in the driveway, the number of beds crammed into one of the basement bedrooms, the commercial dryer caught turning a full load of clothes. But the photos obscured more than they revealed.

I kept a few small relics of my past, a picture I drew when I was six, the cover of a coloring book with all the pages torn out, a baby shoe I stole from a box in the basement; just one. I thought it was my shoe; I wanted to believe it was my shoe, but I can’t be sure. I had asked my mother for any records about me. Anything. She gave me a small cardboard box with a handwritten document about when I cut my first tooth and how long it took me to learn to walk. It also contained a few vaccination cards and a cutting of my hair taped to a small piece of cardboard. I wondered as I thumbed through the contents if any of it was true. Did she fake the vaccinations? Was that really my hair?

As I delved deeper into my research, I realized that the most reliable evidence I had were memories. It was like sitting in the middle of a room, surrounded by thousands and thousands of sheets of paper. I knew that among these piles of paper, these fleeting, unreliable memories, was the truth of my experience. I didn’t have facts that could support my memories. I didn’t have proof and I didn’t have the answers to my many questions. But I had the subjective, the personal experience, the murky water.

I had what it felt like.

What it felt like to look down the two long dining tables at my many brothers and sisters and know that we belonged to each other; to listen to the familiar sound of five sisters sleeping in the darkness near me, the comfort of anonymity, of blending in with a crowd of children around my father’s knees, the feeling of being inexplicably part of a whole. I can tell you what it felt like to be stared at and mocked by neighborhood children who called us plygs when we squinted through a hole in the backyard fence or dared to show ourselves outside the front gate, to peer through the slightly parted drapes at the kids walking past our house, wondering what high school must be like. And I can tell you exactly how the asphalt road felt under my body in the middle of the night, as I waited for a car to see me too late, to end me, only to save myself at the last second.

I cannot prove that any of it happened.

I cannot even prove I was born.

But somehow through exploring the felt experience, I discovered the answers to an uncertain life. I found versions of myself I would have normally turned away from and discovered I had felt strange loyalty to those who hurt me, and also great shame and humiliation for being abused. I uncovered grief for losses I could not name and found love in unexpected places.

Facts cannot get at this kind of reality, the perceived reality: the bias, the assumptions, the judgments, the confessions, the memory that is not quite a memory, the unprovable. All the things most nonfiction writers try to avoid and exactly what memoirists must reveal. Somewhere between the details of the facts and the details of what it felt like lies the essence of memoir.

SUSANNA BARLOW is a full-time writer. Her memoir Not in My House is about her life in a polygamous family and how she overcame the struggle of surviving abuse. It won First Place for Creative Nonfiction in the Utah Original Writing Competition 2017. An excerpt of her book was published in Artists of Utah 15 Bytes in 2018. She enjoys helping other writers with one-on-one writing guidance and as a developmental editor. You can find her online at susannabarlow.com and on Twitter.

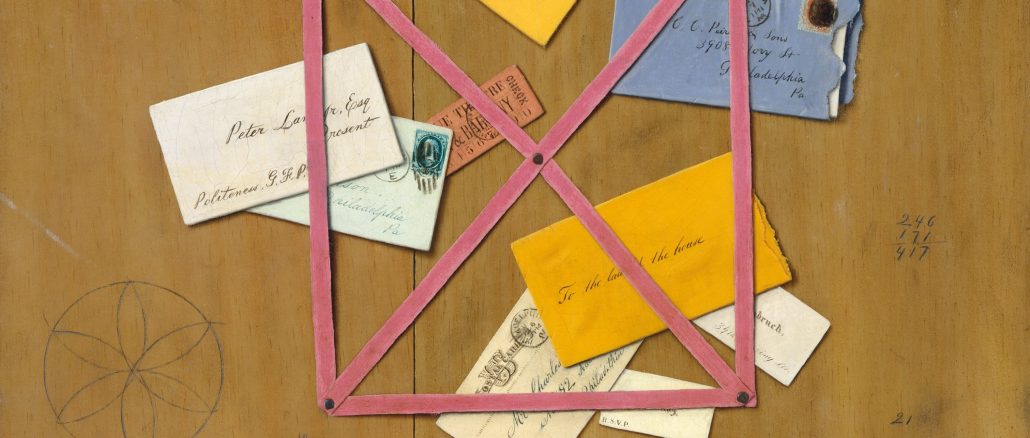

Featured image: William Michael Harnett, “The Artist’s Letter Rack,” oil on canvas, 1879, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1966, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.