“To Helen, a Handbasket” takes a commonplace object—a basket—and uses it as a device to trace the author’s grandmother’s life from her early existence as a dutiful farm wife filling picnic baskets to her final incarnation as a drug-fueled kleptomaniac breaking glass baskets in airports.

The avenues into exploring any life are abundant; they are also, by nature circumscribed in their vantage, though this does not necessarily render them entirely short-sighted. Biography and memoir are, by nature, selective and at least somewhat arbitrary. How, for instance, do we settle upon the symbols or signposts that will offer the greatest insights into a particular soul? No set of assigned criteria safeguards against subjectivity; we must tell what we see and understand – even if that practice opens us up to charges of caprice or partisanship. If this sounds like an apology or defensive, perhaps it is, especially since I propose to offer one potential reading of my grandmother’s life as it was accessorized by an ordinary, and indeed arbitrary, object.

I put forth here not an exhaustive or encyclopedic vision of her life, but instead a rumination to usher forth glimpses into a complicated existence that might be as fruitfully explored by examining one of any dozen objects (or more) that figured prominently in her existence. This style of study is a conceit; I adopt it here to mimic taking a tour through an antique shop – something Gram absolutely adored. Rather than offer clichéd comments about “wishing these items could talk,” however, I intend to tell their tales, rendering them somewhat more alive as I enliven her as well. As I have said, my grandmother lived a life of objects and she did not experience them as either dead or inanimate; they electrified her life and fed her imagination.

From her earliest days, she was trained into this way of thinking and as far as I can tell, she never entirely escaped the sense that she had arrived to the party too late. The sensation of that loss, of having arrived after the fun never left her. Her father drilled his children to learn genealogies of family possessions; he insisted they understand what he considered the extreme importance of possessing fine objects in order to lead a quality life. If this sounds materialistic and shallow, it is hard to deny that it is – at least in part. It is necessary to understand, however, that Helen and her entire family saw something more spiritual – and secure – in beautiful objects. They sought synthesis and transformation in the beauty they found in objects others might simply dismiss as bibelots. Misguided as this may seem, it was their modus vivendi, and it must be embraced – at least theoretically – in order to enjoy the possibility of possession.

From her earliest days, she was trained into this way of thinking and as far as I can tell, she never entirely escaped the sense that she had arrived to the party too late. The sensation of that loss, of having arrived after the fun never left her. Her father drilled his children to learn genealogies of family possessions; he insisted they understand what he considered the extreme importance of possessing fine objects in order to lead a quality life. If this sounds materialistic and shallow, it is hard to deny that it is – at least in part. It is necessary to understand, however, that Helen and her entire family saw something more spiritual – and secure – in beautiful objects. They sought synthesis and transformation in the beauty they found in objects others might simply dismiss as bibelots. Misguided as this may seem, it was their modus vivendi, and it must be embraced – at least theoretically – in order to enjoy the possibility of possession.

For possessed they were; by the past, by possessing, by the inherent possibilities of objects. More than any people I have ever known, the Porters structured a significant segment of their sense of self around objects. Jewelry, furniture, glassware, paintings, and porcelain – to name a few of their fascinations – all operated as avatars, in the totemic sense, of a rich personal and paternal history. As such, all beautiful objects – though some more so than others – assumed essences of the spiritual, the magical, and the puissant. As a result, I have always been fascinated by the relationship between people and objects, and especially the ways in which we invest power in, as well as draw it from, the material world.

As with the Cartesian split, it has become common to sever any substantive relationship between our animate selves and the inanimate objects with which we surround ourselves – though minimalist and anti-materialist movements decree that we must not. Objects, we are told with increasing ferocity, are clutter; rid yourselves of them. Experience is the way to live; give one another vacations or gourmet meals on holidays instead of tangible objects as gifts – that’s the key to a quality existence. No one will want to inherit that stuff, anyway, and before you die it will simply sit, inert, collecting dust.

Except for some, this is simply not the case. My grandmother – and many people in my family, for that matter – found (and find) genuine enrichment and inspiration in the beauty with which they surrounded themselves. They were not the unwitting participants in an early, unfilmed version of Hoarders; they heartily ascribed – as I do – to a philosophy that asserts that our environments matter. What we surround ourselves with impacts our sense of creativity, comfort, and culture. That does not make them mindless materialists or deranged acquisitionists, though certain strains of contemporary thought would say it were so. Their understanding of their stuff was both nuanced and neurotic; it was also productive and problematic.

For Helen, handbaskets – and a great many other objects – were part of her highly developed interior imaginary. These objects signified and embodied histories; I use the plural here because in my family we are taught to conceive of objects as having survived certain verifiable events in the past. This history is fairly prosaic, in some senses, but as the Porter past is checkered with tragedies too numerous to count, it may be so only in the sense that it survived some mishap or another. Some objects didn’t survive, and yet their histories have; they were that significant. More importantly, perhaps, is the ability of these objects to evoke emotion and atmosphere; they have feelings and moods attached to them, as I’ll explain.

This matter is not mindless, no matter how de rigueur is has become to relegate belongings to that state. These objects may seem dead, lifeless things to anyone unfamiliar with their story. But I ask you to suspend this contemporary sensibility and venture forth with a rather magical one in which the things we keep take on talismanic features. They can conjure and caretake – and yet, without caution they make also overtake and distort. At this point such assertions likely sound abstract and oblique, so it’s probably best to proceed so that I can start making sense. If this sounds heady and perhaps a bit purple, I’ll not disagree; it is a world of their construction.

***

Southerners have a saying for when someone – usually female – loses it: “she dropped her basket.” It means the she – whomever that might be – had a meltdown and could not carry her burden of responsibilities for an indeterminate amount of time, though it is always a period that comes to an end. There are other, darker phrases for those who lose control and never recover – basket case being one, though few people understand its original meaning from the First World War. Those darker phrases have relevance here, too, but not immediately.

As I have said, their basket, as far as her family was concerned, had already dropped by the time Helen arrived. All the grandeur and glory of a family who had stolen their land from the resident Native Americans and made a fortune transforming it into farmland had been forfeited.

The temptation here is always to ask why. How does a family that owns nearly the entirety of a county come to control virtually nothing, virtually overnight? Though I could speculate and offer snippets and secrets, the answer is that no one actually knows. Those who did know details died half a century ago and left little behind. Helen knew some truths, in an impressionistic way. Something bad enough to take the entire family’s fortune had happened; family lore said it involved gambling and one of Helen’s uncles. Therefore, it is best not to get mired in the forensic aspects of their story; impressions and vague imprints are all that remain.

Throughout her life, Helen would drop her basket many times, as would those around her. She did her best, figuratively speaking, to pick herself up, collect the contents, and start again. These are those moments, embodied as objects, catalogued as an inventory:

A Bride’s Basket

By the time Helen arrived on June 11, 1923, her mother, Vieva, had kept her bride’s basket as the centerpiece on the dining room table for nearly fifteen years. It was a clear pressed glass piece in a pattern resembling “Thousand Eye” with its endless oculi refracting and reflecting light and the colors and contours of the contents, which changed regularly. Though she knew it had been among the least expensive of the gifts they received, it meant a great deal to her nevertheless. To add to the illusion of its grandeur, she bought a round table mirror trimmed in silver plate to render the piece even more prismatic and impressive. When the money was still plentiful, it often boasted bounty: fresh fruit or flowers from the grocery her husband owned; on special occasions it held a stack of sweets.

Vieva had received her basket just as the custom was going out of fashion. They had first become popular as gifts in the mid-nineteenth century when women of a certain class were gifted elaborate baskets wrought in sterling to showcase the bride’s bouquet after the wedding ceremony and then flowers, cake, or other sweets after taking up permanent residence. By the 1880s, this fashion became more accessible as silver companies produced plate versions and glassmakers offered blown and pressed counterparts. These, though less expensive, were no less ornamented; they often featured various symbols representing good fortune, fecundity and, of course, love.

The gift itself was highly symbolic, though, regardless of the specific ornamentation. Brides received them as symbols of their potential happiness; they were intended to be displayed prominently on a dining room sideboard or as a table centerpiece. They were to be contrived to advertise abundance as well as domestic delight. They might even has served as a kind of precursor to Instagram or Facebook tableaus orchestrated, at least partially anyway, to inspire jealousy and competition among other wives. The best among them changed their displays daily with seductive homemade sweets or ostentatious floral displays.

Their primary appeal was allusive, much like the wedding ring itself. Many brides were bamboozled into believing that a sterling basket symbolized being set for life; a cheap version like Vieva’s suggested a correspondingly sad story which, in her case, turned out to be right. She didn’t believe that superstitious, snobbish nonsense though. She was marrying into money and everyone knew it, she didn’t need a basket declaring it to the world. Besides, she couldn’t have cared less about his cash; she came from a poor background populated by people she loved. Wealth did not necessarily make people worth knowing, even if her husband disagreed with her in that regard.

Nevertheless, she loved her basket. She considered it a creative container to beautify her home and celebrate their love. She liked that people expected her to showcase some silver monstrosity with cherub and garland engravings and that she disappointed them with something far more simple. They already talked about her behind her back as a social climber – which she was not – so she had no interest in owning the trappings to add to their tall tales. Willie B., her husband, would have bought her any basket she liked, but she was happiest with the one she already had – especially at Christmas time when she filled it full of hand blown ornaments nestled on a bed of pine boughs. It glittered and sparkled in the lamp light, putting shame to its overwrought competitors.

Nevertheless, she loved her basket. She considered it a creative container to beautify her home and celebrate their love. She liked that people expected her to showcase some silver monstrosity with cherub and garland engravings and that she disappointed them with something far more simple. They already talked about her behind her back as a social climber – which she was not – so she had no interest in owning the trappings to add to their tall tales. Willie B., her husband, would have bought her any basket she liked, but she was happiest with the one she already had – especially at Christmas time when she filled it full of hand blown ornaments nestled on a bed of pine boughs. It glittered and sparkled in the lamp light, putting shame to its overwrought competitors.

Though many things had to go when they were forced to forfeit the farms, the basket and its mirror survived. “That’s not worth anything,” her mother-in-law offered with all the condescension she could muster – though she was now, too, a pauper. Her basket, to be sure, was sterling and despite its fine pedigree she could not give it away – let alone sell it – after their collapse. Brides were superstitious about such things; Cora Belle’s basket was tainted in an incontrovertible way. Despite its undeniable beauty – and value – it could only bring sadness and destruction to the woman greedy enough to agree to adopt it. When John Elmer, Cora Belle’s husband, took it to the jeweler, head hung low, he learned as much and returned to their newly rented house without so much as a dime. “I couldn’t bring myself to sell such a treasured object, Belle. We’ll find some other way.” He couldn’t tell her the truth; the social implications would destroy her.

Children in Vieva’s house learned quite young that the bridal basket was out of bounds. They were welcome to delight in its good looks, but they were never to touch. Only Dorothy, her eldest, really remembered the days when it had been beautiful to behold. Willie B. delighted at delivering his young bride and daughter some delicacy to showcase in the centerpiece. Each night when he returned from the store he would produce treats like dates, almonds, even once a cantaloupe though it turned out to be too large, for Vieva to work her magic. On special days, like Dorothy’s September birthday, Vieva filled dates with fondant and a whole almond, rolled it in sugar, and stacked them up like little soldiers guarding the last of the delicate pink tea roses she had massed in the center in their very own bowl.

Helen heard such stories as a child – when they were surviving on little more than poppy seed cake and sassafras tea – and fairly foam at the mouth. How it is that they lived with such a surplus of poppy seed cake, no one could ever rightly say, but not a one of them – she and her siblings – could stand the sight of it as adults. They mourned the happiness that had halted so abruptly and felt deprived by their damned luck. They even hated Dorothy a little for having had six years to luxuriate in her parents’ love – both as it did and did not involve her – before the next one came along. All three girls, Dorothy, Marjorie, and Helen each dreamed about the day they would take possession of the basket and revive its past as a tribute to their mother.

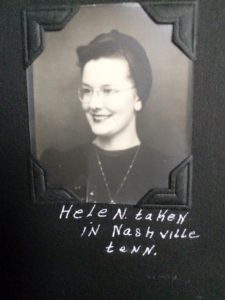

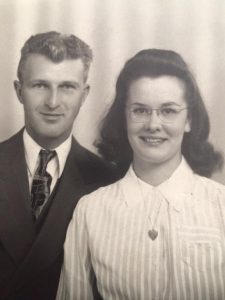

Helen, being the baby as far as girls go, won that battle. Marnie – as Marjorie was called – argued she ought to at least get the table mirror, but in the end Vieva argued the pieces were as married as she was to Willie B. and that was that. Helen, a bride in ’41, received both as her wedding gift from parents who could afford nothing more. Dorothy, who had finally made a favorable match after a major misstep a few years earlier, suddenly had some money and offered to throw the wedding in her home. She suggested Helen bring the mirror and basket to serve as centerpiece for their January wedding, but Helen knew better and demurred. She would not put it past her sisters to break or steal her prize since they felt jilted by their mother’s decision.

Instead, Dorothy bought Helen the bride’s basket she felt she deserved. It was a waffle block pattern – tall, slim, and elegant – made by the Duncan Miller Company. The catch: it was one-quarter the size of her mother’s, the one they all considered the perfect prototype. On a good day, this pretty little piece of pressed glass might hold an object the width of a chicken’s egg, perhaps two eggs deep. It’s an odd standard of measurement, but that’s because some Easters that is precisely what Gram would shove in it. She hated it from the start and heard what it had to say: “You’ll never be Vieva. Lower your expectations. Your marriage is a bad match.”

Her sisters – and really most of her family – always thought she deserved less, and this disastrous gift was no different. She figured they were jealous as she was the only one with looks and her new husband matched them. They could call her stupid, but she knew she had substance. Throughout her life she was never able to part with either basket, though Dorothy’s fated, gifted message turned out to be at least partially true. Her marriage was not happy and though she reveled in those baskets for the first few years of homemaking, it didn’t take long for them to turn into a kind of joke.

Her mother’s, for the majority of Helen’s marriage, stood as the centerpiece on a dining room table that had been her parents’. Because it was ruffled and low-slung, it required many careful contrivances – not unlike marriage – to operate successfully. Rose bowls or other deeper containers could be inserted under the handle to hold water, but then that appliance would have to be disguised. Fresh fruit worked best but again, like marriage, any protracted inattention could lead to unnoticed decay. Gram could easily let fruit rot on the table and not notice it till the house had filled with flies, rendering this symbol of love into something much more funereal than anyone found fetching.

In the end, she opted to fill it with a strange selection of plastic grapes that invited anyone seated at the table to compulsively squeeze and even de-stem them. Gram found this magnetism infuriating; she simply could not understand why we all felt compelled to fondle her fake fruit. I can’t say why either, exactly, but by the time I came along those grapes wore a fur of dust, discolored by decades in the sun. Her marriage to my grandfather, for the most part, had been embittered and it seemed perfectly apropos that an object with which she first associated such joy and then later bitter, brittle happiness should end up as the beautiful receptacle for something so utterly devoid of aesthetic appeal or style.

Picnic Baskets

Helen packed countless picnic baskets from 1946 until 1970 and never ate out of a single one of them. She had been a farmer’s wife since ’41, though she never gave what that meant any thought in the early years. They had, after all, never lived together. They had stayed together when she followed him during Basic Training, but that was more like playing at house than having real responsibilities. Then he shipped out for Europe and she carried on living with her parents. When my grandfather returned from France in ’46, he worked quickly to acquire a lease on a farm about ten miles outside of Monmouth, where she was living. Ironically, the farm was planted in the heart of the fields her family had once owned.

The farm itself was small by today’s standards, but in those days it was perfectly proportioned for him to manage its business most of the months of year. The house was small and abused; it had seen many hired hands and their families. It had only been electrified a year before and still offered no indoor plumbing except a pump in the kitchen. It was uncomfortable two-thirds of the year, but they did the best they could. For Helen, it was a horrible shock; even in their poverty they had never lived in such a place. She knew nothing of outhouses and chamber pots; she had always taken a bath when the mood suited her. Gerald, my grandfather, was largely indifferent to her unhappiness. He expected her to come around quickly and make it all ship-shape.

During the times that he couldn’t handle the work alone – planting and harvesting, primarily – all the farmers in the neighborhood banded together. Helen was amazed to discover the ways of farming since her own father had always worked for the electric company after he lost his own farm. It seemed like a miracle that the men would pitch in and help one another manage the fields and the storage of their produce. Those men always liked her and she enjoyed having them around the farm as they lightened my grandfather’s endless bad moods and fiery outbursts, as he never misbehaved in front of company, struggling as he was (most likely, though never diagnosed) with PTSD and other emotional baggage from the horrors he experienced in the war.

What she was not prepared for during those weeks, however, was the endless meal preparation. For all the joy of banished monotony and much-needed levity, harvest and planting were always the most exhausting weeks of the year as she was expected to provide meals for as many as fourteen men every three-four days. The system worked in rotation among several other wives and usually at least two wives worked each day – and often in the same kitchen. They were expected to provide prodigious amounts of food to the men, wherever they were in the fields. As this was long before any such things as convenience contraptions or time-saving measures, this cooking was more than a full-time job.

Each morning she would arise before the sun and prepare breakfast for the household. Once that was out of the way, pies had to be baked. They always went first because they did not need to be kept hot. She had to produce enough to serve for both dinner and supper; the men expected it. The pies were always fruit; blackberry, peach, and apple were her go-to favorites. Though every farm wife in those days could produce a pretty damn good pie, Helen’s were exceptional – though no one now knows her secret. Her blackberry, especially, had such a reputation that when, after her death, we found a long forgotten, possibly decades-old one at the bottom of her chest freezer, we all thought long and hard about battling the freezer burn just to enjoy it one last time.

She had frozen the fruit for months, working diligently to put up all she could. When those reserves ran out, she ordered frozen fruit – a serious luxury – at the local meat locker. On any given day, she might make 6-8 pies, carefully saving every crust scrap to transform into cinnamon pinwheels to treat the men. Her oven, which ran on bottled propane, could only bake four pies at a time so the entire process took a good chunk of the morning. It also meant that the meals could not require any baking whatsoever. Baking powder biscuits, when they were called for, had to be made in bulk the night before. On the god-forsaken mornings when she gauged the propane wrong, it all went to hell and crisis ensued as she would have to drive like a bat out of hell the six miles to Little York to retrieve more fuel. The men did not appreciate late meals.

The main course was often beef stew or something similar. The ideal was to make enough of something that it could be stretched out for the two meals. It was always a gamble, though, because if the men were really hungry – or overindulgent – at dinner, she might be left scrambling to scratch together the supper. She usually had four hours between, which meant all supplies had to be on hand and there could not be any mishaps in between. In those first years, she made endless commercial-size kettles of chicken and dumplings, beef and noodles, and vegetable soup.

Alongside the main course always came green beans and/or corn, plus mashed potatoes and often stewed tomatoes. You rarely attended any meals at Gram’s house when these weren’t the standard. These were the items my grandfather and his compatriots expected to find and the women, no matter how hard it was on them, complied. It’s really no wonder that most of that generation died from heart disease and other diet-related ailments; the fare they consumed was filled with butter and lard and other pernicious fats. On many an occasion, Gram would carry quart jars of heavy cream the consistency of mayonnaise out to the fields for the men to dollop on their pie.

Once the food was finally finished, transport ensued. One of the women would play spotter, scouting the fields for the men’s location. The other woman then swaddled the pots in wool blankets to keep the food hot and load it into the cab of the truck. Its bed, packed from the preceding meal held the thresher’s table and folding chairs from the church. Once the lead woman returned, the picnic baskets filled with the pies, cutlery and crockery, and wet rags to wash up were loaded into her vehicle. Then thermoses of coffee, tea, and sometimes lemonade were loaded. If anything was forgotten, the men would have to make do. Helen hated that; it felt like a failure. She was their hero when she descended upon the fields; she intended to make herself and Gerald look as good as she could.

But she never ate herself. She fussed over the men with her partner wife, serving and sopping up messes. The men ate like they were starved and she somehow bought what my grandfather always told her: we work harder than you do. She got to stay at home, didn’t she? Of course the minute they stopped eating the women were expected to haul every dirty dish back to the house and make them magically clean again. Their wonderful picnic baskets, chockablock with delights, were suddenly something more like garbage receptacles to be tediously – and laboriously – emptied. On the days when it was “her turn” – like she had won some inestimable prize – she got to go twice.

Once home again, all that detritus in tow – including the re-loaded table and chairs – the entire affair started once more. She knew that the baskets had to be refilled in a few hours and often dreamed of spreading all those dishes out on the lawn and washing them with a garden hose. Instead, she heated water in a stock pot and painstakingly scoured them in a dishpan not much larger than some of the casserole dishes she used to feed the men. Doing dishes alone could take three-four hours of those days. If she was lucky, she would steal away for fifteen or twenty minutes and eat her portion of whatever she had made – carefully reserved from the farming fiends – and imagine what it would be like to run a restaurant where people could offer her similar praise for her culinary acumen without expecting her to eat on the sly. Sadly, she never got that opportunity – though today she might have – and when a heart attack forced my grandfather to give up farming in 1970, one of the first items she contributed to the resultant auction was her very own green-and-tan picnic basket, which had always been used to carry food to others. She felt nothing but relief to watch it go, pitying the poor woman who bought it amidst fantasies about what fun it would be to fill it for her family.

Bushel Baskets

Life on the farm taught Gram all about the sentence of hard labor. Though she had certainly helped preserve food in Vieva’s household, she had never been saddled solely with the responsibility. Gerald expected her to know how and when to do such things, without explanation or prompting. As a young bride at Vieva’s, she might stir, add sugar, or sanitize jars, but she never took on the entire task start to finish. In the first few years it was overwhelming; she could not believe the endless labor of life on a farm with no extra hands to help. Her eldest daughter, Barbara, was too young to be of any use and the ten or so miles to Monmouth may as well have been a hundred. Her nearest neighbor, Jeanette, had her own putting up to do – in fact, it seemed to her that putting up was all farm women ever seemed to do.

The work started in May with strawberries and stretched until September when the apples were finally spent. The beginning of each fruit’s season brought fun; lots of ladies in the neighborhood would gather for the gleaning. These days were similar to those when the men planted or harvested, except no one showed up with their dinner. In fact, they all had to disperse for a few hours midday to create hot lunches and do up all the dirty dishes. Then it was back to picking, which really meant mindlessly pulling fruit while gossiping, laughing, and generally learning about one another’s lives. These were moments of relief followed by sore arms and bushel basketfuls of fast-fading fruit.

The day after picking was always punishing. Some fruit was more forgiving than others; apples, for instance, could be hauled to the cellar and carefully removed from their baskets onto a bed of newspaper and kept for months. Sometimes they lasted almost till the next harvest. Pears and cherries could sit a day or two at most. Peaches, on the other hand, often should have been processed before they were even picked. They were fussy, infuriating fruit – truly the pits. In northern Illinois the trees don’t perform well and require constant attention. Gerald loved peach cobbler, though, so foregoing the fruit was off the table. He tended the troublesome trees and she managed the rest.

Illinois peaches are a pale imitation of their southern sisters; they tend to sport a greenish cast even when ripe. They are also, on average, about one-third of the size of some from the South. Once the pits are removed, it takes a basketful to make a cobbler. While Helen would have been just as happy to buy the canned variety she was starting to see in the store, Gerald would hear none of it. His mother had contended with peaches, Helen could just follow her lead.

Throughout their marriage, these peaches were a point of contention. Her family expected preserves, pies, and cobblers. The pursuit of meeting this perfection would teach her some of the most painful lessons she would learn about life as a farmer’s wife. The first happened when preparing preserves. After the endless peeling of their unpleasantly furry skins, she would extract the flesh hugging the porous pit. She did this with the precision of surgeon, wielding a paring knife she had sharpened into a scalpel. When all this work was done, the largest roaster she could fit in her oven was filled with the fruit, along with a five-pound bag of sugar, a pound of brown sugar and the entire concoction was baked at high heat until it transformed into a peach-flavored sugary sauce.

While it reduced, she often snuck into the bedroom for a nap. My grandfather rarely ever returned to the house during the day – he heartily disapproved on day-sleeping – so she took the risk of resting. Their bedroom was next to the kitchen, so she could monitor the smell of her concoction to make sure it wasn’t turning to caramel or, worse yet, burning. Her nose had become so attuned to culinary scents that she never needed a timer and she could will herself to awaken just to intervene in whatever alchemical alteration was afoot. Except for that fateful day with the peach preserves, that is.

She fell asleep more deeply than usual and awoke to the smell of smoke. She lived in terror of fire ever since the landlord told them that an entire family had perished on this spot when the house that preceded their own had gone down in flames one night. In an instant she flew from the bed into the kitchen. As she opened the oven door she realized the boil had become too boisterous and the resulting splutters and spatters were incinerating on the oven walls. While it didn’t smell great, it wasn’t a big deal. She grabbed two tea towels and set about taking the roaster from the oven. She didn’t realize one towel was slightly wet, which meant the heat instantly shot through it as she picked up the ponderous pan.

In an instant, she lost her grip and spilled molten peach lava down the entire front of her body. The pain was overpowering as the sticky sugar adhered to her thighs and shins, easily penetrating the thin cotton of her housedress. She swooned, dropping the pan at her feet as she expected to black out. Braced against the table, she fought losing consciousness as she started to cry out – all while wondering about the horrible smell that had filled the room. Where had she gone? What was happening? She couldn’t keep track of her thoughts as she screamed and realized there was no one there to help.

The smell, it suddenly came to her, was that lava liquid cooking her skin – a realization that turned her stomach so violently that she then retched the morning’s eggs and toast into all of her spoiled jam. This horrifying side effect somehow calmed her enough to stabilize the situation somewhat as she gathered the courage to look at her legs. The damage was unimaginable; she surveyed skin that was nothing but seemingly one giant blister. On her thighs, skin hung in ribbons. Nausea swept over her once more and this time she vomited directly onto the kitchen table and then passed out for a minute. When she revived, she knew she had to do something. Gerald would not be home for hours; neither would Barb or Patty. As always, she was on her own.

She could not summon the energy to prime the kitchen pump so she could wash off with water. The thought of touching her legs left her sick with disgust. She felt certain she would never survive this. Would they all return home to find her dead? She couldn’t do that to her girls. She had to figure out something to survive until someone else could help. In a moment of madness, she remembered some old wives’ tale about smothering a burn in butter. Recognizing that she had no other plan, she jammed her hand into the butter crock at the center of the table and began smearing it on her thighs as she screamed out in pain and fought back puke.

Somehow, in the midst of all this, she managed to pull out one of the chrome kitchen chairs and sit down, which only heightened her excruciating pain. Never one with a high tolerance for it anyway, she suddenly started to understand how people completely leave their minds when something terrible is happening. She felt as though she were a firsthand witness, but not exactly in the action she was performing. The sensation was terrifying; she started to wonder if this was how dying felt. Or perhaps she was losing her mind? Would her family return to find her feckless?

She sat there, slumped over the table, feet cemented by sugar to the floor, for what seemed an interminable time. As she slipped in and out of consciousness, she awoke each time to discover the hell farm life had created for her that morning. “Goddamn peaches!” she kept telling herself, promising never to touch them again if she survived. At some point, when she could stand it no longer, she somehow managed – through one swift heave – to break free from the sugar cement and stand up. No more had she done so than another wave of nausea descended and she was vomiting again – though there was nothing left to produce. As she fought through, she took small steps toward the bedroom; if she was going to die, it would be in bed.

All her life Helen extolled the virtues of spending life luxuriously in bed while someone waited on her. She dreamed of such decadence. Bed was often the only place that ever seemed safe – especially during the day when the house was abandoned and she could lay there and survey her possessions, telling herself whatever tale she liked. It seemed fitting, then, that she would retreat to that spot in this, her moment of utmost agony. With a thick spread of farm-fresh butter, she plodded forward, fighting dry heaves and crying out with each new step. After seemingly hours, she turned to face the doorway and dropped her body in one fell swoop onto the mattress.

Her knees screamed out in anguish as she made contact, bursting forth with the blister fluid down her shins. This time she blacked out for the better part of the afternoon. She came to briefly and locked eyes on “The Old Farm House,” a Currier & Ives print hanging on the wall. The house and outbuildings rather resembled their own. It made everything about this life seem so idyllic and quaint. “I bet Currier & Ives never made a ‘Death by Peach Preserves’ print,” she thought ironically as she imagined sitting – or rather laying – for the iconic printmakers.

When she next awoke it was because Gerald had entered the house with the girls. Screaming and shouting ensued, though Helen could make none of it sensible. It was just another commotion with which she could not cope. Barbara screamed “Mommy! Mommy!” perhaps thinking she had gone on to greater rewards. Gerald kept grunting – he never seemed to speak anymore until the swearing started – and then he finally blurted out “goddamit! What have you done?” If it was tender mercy she wanted, she had married the wrong man. He was furious to return home to a house that smelled sickeningly of burned flesh, peach preserves, and puke. For him, odd as it may sound, it served as a jarring reminder of the war – minus the peaches, of course.

As they had no health insurance or disposable cash, he did not whisk her away to the doctor. He had grown up in a household where one suffered through afflictions and hopefully lived. His sister Katherine, suffering a severely impacted bowel, succumbed at age 5 because his own father would not risk debt to prevent death. Gerald’s mother was so traumatized by the loss that she actually had the child exhumed and moved when the family relocated to another county. She herself would also experience a stream of torment in her later years after taking to bed with a terminal illness which she labored against largely without the assistance of a doctor. Her husband, however, in the end – perhaps as recompense – did throw her a somewhat lavish funeral to celebrate her stoic suffering.

“You have to take me to the hospital,” she pleaded. “Put me in the back of the truck if you have to.” But he did not. Instead, he headed to Monmouth to track down Helen’s mother, Vieva, to task her with nursing his wife. Never mind that Vieva had a job as a copyeditor at the Review Atlas and endless other responsibilities of her own. Someone had to care for the woman and it never crossed his mind that it could be him. Men didn’t do such things; it was women’s work. So Helen lay there in bed – periodically unconscious – for weeks on end. Vieva came to help and tended the wounds and the children. She also scrubbed down the entire house to kill the godawful smell. Not once did Helen receive any medical treatment for her catastrophic injuries.

“It’s a wonder she didn’t get gangrene,” my mother often says just before she recites her own litany of horrific childhood injuries she survived without the benefit of a doctor’s attentions. It became a kind of twisted badge of pride among them all that they healed on their own. Of course no one ever talked about the psychological damage that caused or the toll it took on their bodies. Somehow, miraculously, with the help of Vieva’s nursing and some so-called “Grandpap Salve” that she made herself, Helen’s legs healed, if you could call it that. They were hideously scarred and she never forgot that Gerald would not take her to the doctor. It was one of the many stops put in place that never got pulled again, as their relationship grew increasingly adversarial.

For the six weeks she lay in bed after the accident, she did little except enjoy the few bits of finery she could see from her vantage, reading novel after novel. She slipped slowly into a greater sense of fantasy about life; she grew less and less certain about what was real and what she had imagined. Never again, however, would she look longingly at the idealized – and patently false – life portrayed in those charming Currier & Ives scenes, which were clearly executed by someone who hadn’t the slightest idea what farm life or the so-called “real America” was really like.

The following summer when she suggested that she would not be processing peaches again, the entire family fell apart. “We love peaches!” all of them screamed in one way or another, eliciting guilt and a sense of duty in Helen. She was truly terrified to make preserves of any kind ever again, truth be told – but the realities of her life left few options in that regard. So she soldiered forward and acted as though she wasn’t forever remembering that excruciating afternoon when she had been boiled alive in jam and then smeared with butter, like a human crumpet. Much to her surprise and relief, the season passed without incident and she regained her confidence in the kitchen.

The following summer as she sat peeling peaches – her least favorite function – she smiled when she finally found the bottom of the bushel basket. As she stood to pour herself a glass of tea in reward, she violently wrenched her right knee when she slipped on an errant peel that had slipped just under the edge of the chair. The damage was so severe – and of course went untreated – that it never truly healed. She would spend the rest of her life limping and suffering because of her family’s insipid obsession with peaches. She would not, however, drop that basket again; the peaches were prohibited permanently from that point on. “If they want peaches that goddamn bad, let them fix ‘em themselves,” she was heard to say to friends on more than one occasion.

An Opalescent Cranberry Glass Hobnail Basket

It’s not easy to narrow down the baskets in Gram’s life that tell important tales to just three. There were countless others that offer insight into her personality and experiences. I might, for example, spend any number of pages telling you about how after she had given up on any resurgence of romance in their relationship after WW II, she started to gather various baskets on the Early American-style rock maple end table that sat between her chair and my grandfather’s in their living room. These baskets were made of that heavy milk glass so popular in the ‘fifties; they were embossed with pansies or clusters of grapes. She also added several Sѐvres painted porcelain baskets of various shapes, all featuring gilded handles and delicate floral hand-painted decorations alongside rather serious chips and/or cracks. Had they not been damaged, she could never have afforded them. This was her way; she would rather have ten damaged beauties that a single pristine one.

It’s not easy to narrow down the baskets in Gram’s life that tell important tales to just three. There were countless others that offer insight into her personality and experiences. I might, for example, spend any number of pages telling you about how after she had given up on any resurgence of romance in their relationship after WW II, she started to gather various baskets on the Early American-style rock maple end table that sat between her chair and my grandfather’s in their living room. These baskets were made of that heavy milk glass so popular in the ‘fifties; they were embossed with pansies or clusters of grapes. She also added several Sѐvres painted porcelain baskets of various shapes, all featuring gilded handles and delicate floral hand-painted decorations alongside rather serious chips and/or cracks. Had they not been damaged, she could never have afforded them. This was her way; she would rather have ten damaged beauties that a single pristine one.

These decorations may seem fairly anodyne and in keeping with that era. The strange thing about them, though, is that they were filled with tweezers, nail clippers for fingers and toes, nail scissors, cuticle pushers, miniature hand mirrors, and various other implements for personal maintenance. She liked to keep these items close at hand so that she might attend to her personal needs while they sat in front of the black-and-white television watching some program or another. For the woman who initially refused to let her man see her in curlers, this was quite a comedown. My grandfather resented greatly that Leave it to Beaver or Gunsmoke was forever punctuated by the crisp click of toenails being sheared or the silent, yet still intrusive, pruning that perennially transpired on Gram’s brows. He brought her to a house with no bathroom, so she performed her ablutions in the living room instead.

I might also return to the tale of Gram and the sterling centerpiece bowl with its fancy glass insert which was also, in fact, a bride’s basket. She coveted that curious confection from the Victorian era from the moment she first saw it; “surely,” she thought, “that must be like Cora Belle’s.” It featured a highly ornate base with a boy and girl playing, with the bowl suspended over their heads. It belonged to Curt, her much-despised brother-in-law, who had married Marnie. Each summer, Marnie and Curt would protest that they simply could not care for their girls, Helen and Jenny, when school was out since they worked all day. Helen, ever her family’s pack-mule, took on the task. The girls would be dropped in late May and stay till mid-August.

Helen loved her nieces like daughters and their extra hands, after a certain age, were certainly welcome when it came to kill and pluck chickens, tend the garden, and, of course, put up fruit and vegetables. During those months, though, their parents rarely ever visited despite living only an hour away. Marnie always promised to send a box filled with surprises, but the surprise always turned out to be that the box never arrived. No matter how kind and helpful she was, her siblings took advantage – which hurt all the more because they were all far more financially successful, lived in nicer houses, and had finer things. When Curt’s mother, old Grandma Lind as she was called, died and left him that bowl among other things, Helen was beside herself. She wanted it so badly she could barely stand it – especially since it wouldn’t fit into their tacky midcentury modern house at all.

In the years after, she would cajole Marnie to give it to her whenever they were alone – always to no avail since it was a family heirloom. Shortly before Marnie died young of breast cancer in ’69, however, she managed to “borrow” that bride’s basket for a party. When it came time to give it back, she balked. She simply could not make herself do it. So she lied and said she’d broken it. She had found out that Curt had been unfaithful and she saw stealing the bowl as a fitting punishment for him. After Marnie died, there seemed to be no point in returning it. She would vicariously achieve her sister’s vengeance through theft. So she kept that particular basket – wrapped in a stolen hospital gown – hidden in her hope chest for the next seventeen years. Everyone knew she had it but no one knew where to find it. They also knew there wasn’t a chance she would give it back. It was finally returned to Curt in ’86 after Gram entered a nursing home. He sold it shortly thereafter, leaving my mother to wonder if she had been right to give his basket back.

I might also regale you with tales of the endless laundry baskets Gram compulsively bought as storage containers in the days before Rubbermaid bins were widely available. As a kid her dining room was always lined with them; some did hold dirty laundry. Most, however, offered an assemblage of items, many of which were stolen. There was no logic to this system, except in her own head and we were all forbidden from getting anywhere near them. She was paranoid, you see, that we might take some of her stuff. So paranoid, in fact, that at one point she did accuse a nine-year-old me of stealing a pair of diamond earrings in antique basket settings. We never found out their fate, but I certainly had not stolen them.

The laundry baskets were best at holiday time. On Christmas morning my father would always have to drive to Monmouth to collect them and carry back the baskets she had filled with our seemingly endless presents. Unlike other people, however, Gram rarely gave us anything new. In fact, her trademark move was to give us fenced goods that she had stolen from a variety of sources. My siblings didn’t really appreciate these gifts; if she sensed that was the case, she often stole them right back. I, on the other hand, loved old things and so I was always delighted when she gave me antique books – usually stolen from the public library or someone else’s house – or some other age-inappropriate objects. One Christmas she gave me an entire set of engraved brass bells. I was stunned; at seven years old I had no idea what I would do with them. Apparently the look on my faced didn’t satisfy her when the box opened, so by New Year’s they were mine no more. So it went. A big part of the fun was discovering the oddities with which she presented us and then hearing my parents’ commentary about them later on – usually after they had “disappeared.”

Perhaps the best – or at least the most important – basket story involves a Fenton Art Glass Company’s opalescent cranberry glass hobnail basket that belonged to my aunt Barbara after she married her first husband, Bill. Both of Helen’s daughters inherited a kind of mania for glass baskets because of Vieva’s bridal basket, so it seemed like something of a victory – and a filial achievement – to acquire another example to enjoy. Those glass baskets are plentiful at flea markets and antique stores these days and one can hardly give them away, they’ve fallen so far out of fashion. In the early 70s, however, they were still desirable and collectors coughed up serious cash to buy these mass-produced marvels. Cranberry glass, especially, caught their eyes and Barbara felt owning one conferred upon her a status heretofore unparalleled among her peers.

After her marriage fell apart, however, it was difficult to continue fantasizing about it as her very own bridal basket. In fact, the basket, along with a great deal of other art glass, had ended up in my parents’ basement in Fort Collins, Colorado, where the entire family had migrated for a time after my grandparents were forced to give up farming. My mother and her sister were both married women by this point; Barb and Billy had moved first, then my parents, then, in ’71, my grandparents. The adjustment for them had not been easy; they had no idea how to live away from the farm that had been their home for twenty-five years. After her children had left, Gram had become increasingly erratic: she stole everything she could with abandon, including prescription pills.

Her favorite was Valium because she could not handle her difficult marriage and a million other serious family problems. She was always the go-to when trouble came, and it took its toll. When Gerald had a heart attack in ’70, they knew he would no longer be able to work. They held a large farm sale and sold bushel baskets, grain baskets, and everything in between. Helen still left with a fair hoard, but she never got over the loss of her possessions; she continued forth with the Porter sense of perennial loss. In 1971, for the first time in their lives – he was 54, she 48 – they bought their own house. It was a small Victorian with ample shelves for her glassware, and for a moment it seemed like they might be happy.

Except she carried baskets of baggage with her and could not adapt to her new environment. She started to hate everything and everyone. She was verbally and psychologically abusive to Gerald, who returned her tactics in kind. She was explosive and the least little thing could send her into a blind histrionic rage. She stayed up most nights listening to big band music, keeping my grandfather awake. She called her daughters nonstop with ridiculous requests, being as surly and snide as humanly possible all the while. It seemed like something had snapped; after years of heaped-on abuse and hardship, she’d had enough. Now she intended to let everyone know how unhappy she had always been.

Except for her next door neighbors, Margo and David, whom everyone else hated. Margo, especially, could do no wrong in Helen’s eyes. In fact, to hear Gram tell it, she was the daughter she wished she’d always had. This, most likely, was a ploy because she knew it royally pissed her real daughters off. They loathed Margo – who was a total bitch – and only doubly more so because their mother had made her a mascot. Every time they saw their mother it was always “Margo this” and “Margo that” – so much so that they made a habit of saying the most foul things they could imagine about her just to aggravate the situation further.

Everything came to a boil when Gram invited her daughters to lunch one day and they parked, legally, directly in front of Margo’s house. They had no more than closed their doors when she popped out, smarmy as could be and said “Could you girls move that car? David likes to park there when he comes home for lunch. Thanks!” My mother and her sister, disguised sailors on shore leave that they sometimes were, angrily moved the car forward six feet and got out grumbling and cursing Margo. This continued as they entered the house.

“She’s such a goddamn bitch,” Barbara mumbled to my mother. “It’s always David is a cop. David could arrest you. We’re important people.” To which my mother pointedly replied, “What a cunt.” When Gram overheard snippets of this, she already knew what was afoot even as she played dumb. “Who are you talking about, girls?”

“Nobody. Doesn’t matter,” Mom stonewalled, hoping to stave off a fight.

“Doesn’t sound like nobody. WHO ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT?” she bellowed.

“That goddamn bitch next door, MOTHER!” Barbara barked, lighting the fuse.

“I LOVE Margo! You CANNOT talk about her like that. She treats me better than you two ever have.”

“She’s a snotty piece of shit, Mother. You only stand up for her because you know we hate her,” mom fired back.

“GET OUT! GET THE FUCK OUT OF MY HOUSE!” she shrieked as she jumped up and down. Stunned, neither daughter knew whether to take the exit or shelter in place. Neither was likely safe, especially since she was certain to take this out on their father once they left.

“I’m not kidding!” she screamed, “get of here you ungrateful little bitches! I’ve had it!” And at that she launched toward them, grabbing the bag of hot dog buns she had asked them to bring. As they fled the front door, she kicked open the screen and continued the onslaught. “I don’t care if you EVER come back! You’re both going to HELL IN A HANDBASKET!” And then, as if almost an afterthought, she launched the bag of buns at them, screaming, “and take your goddamn buns with you!” Margo, delighted at the mischief she had made, mockingly laughed in plain view behind her picture window.

This moment, sadly, would become fairly stereotypical in terms of tone and temper over the next fifteen years. While she had always demonstrated a certain flare for causing scenes and throwing tantrums, they usually occurred infrequently. The move had left her mental health in tatters and she would not even begin to think about seeking help. It is also possible that her hoard of pills had run rather low since her new location left her cut off from her usual supplies. Either way, she was explosive and aggressive and no intervention could calm her down. They made it approximately two and a half years in Colorado before they abruptly announced they would be returning to Illinois for good right after Christmas of ‘73.

At the same time, Barbara’s marriage was falling apart and she moved out of her house. While she left many of her personal possessions behind – one of the great tragedies of Gram’s later life – she did pack a few boxes that she promptly deposited for safekeeping in my parents’ basement. This abandonment became a flashpoint for Gram. She could not imagine how her very own daughter could simply walk away from all the beautiful things she owned. She had far more at thirty than Gram could hope to have in her years that remained. She was furious to think that all the things she had bought and made her over the years were about to become the property of the next woman Billy took up with. It was like the Porters all over again; none of Barbara’s history would be saved in this upheaval.

Because their house was nearly packed for the move, Gram and Papa were staying with my parents for the holiday season, which made everyone’s life hell. Gram continued her erratic habits and horrified the entire family by grooming herself in the middle of the living room and starting a small fire with a tea towel in the kitchen. She said awful things and overate; she only behaved when my father was around – and even that had its limits. Late at night when everyone else was in bed, she would rifle through drawers and cupboards and suddenly things would come up missing.

While everyone had suspected for some time that Gram was a kleptomaniac, no one had hard proof. Objects inexplicably appeared – always accompanied by some rum story – and became part of her mythology. She acquired paintings and other decorative objects that she claimed were part of the Porter collection. She insisted that rings and other jewelry no one else had ever seen were family pieces she had been keeping hidden. As she had always been secretive in that way – she even hid a store of chocolate in her underwear drawer – this proved somewhat plausible. Deep down, however, everyone knew she was up to something somehow dishonest. They had mostly decided, however, that Helen was ferreting away funds to spend on herself or she was running up credit somewhere.

She had done that very thing for years when Gerald would not give her adequate funds to pay for clothes. Left with no other option, she simply opened a credit account with a catalog company and ran up a huge bill over fifteen years, paying only the minimum payment each month. He nearly keeled over when he found out, but his histrionics garnered little sympathy when they learned the reality of the situation. How else was the poor woman supposed to clothe her kids? Where did he think their own modest wardrobes came from? Her daughters figured that once they had left the house their mother was finally enjoying slightly more financial freedom and treating herself to a few things. Gerald never noticed any of their possessions, so who were they to interfere if she was enjoying herself? If people would stop asking about them, she wouldn’t have to lie at all.

That, of course, was not the case. She had been stealing here and there since the 50s and with more time on her hands – as well as more drugs in her bloodstream – she was able to dedicate herself more fully to the art of the steal. Unfortunately, that did not work so well when she moved to Colorado. She wasn’t cleaning houses for money any longer so the only places she really went were her daughters’ homes. And then Barb left Billy and that meant only Patty’s house to patrol. She knew she couldn’t get away with that, so she just mostly did without – she couldn’t get a satisfying fix anywhere.

Once she was certain they were leaving Colorado, though, all bets were off. Her first mission was to reclaim the antique Porter photos she had shared with mom. Barb’s half were who knows where – maybe even the Salvation Army – but she was damned if Patty would do the same, despite having given them to her only a year or so earlier. So one night after everyone was in bed, she snuck into my older brother’s bedroom and stole the whole bunch from the glove drawer in the antique dresser where they lived. Mom would not notice this theft for many months and for a very long time would assume, sick with fear, that they had been lost in a recent move. Her mother had never stolen from her before, so it didn’t cross her mind that such a caper was afoot.

Over the course of the holiday weeks, little things came up missing here and there. Sometimes it was just food and everyone assumed someone else was overindulging and brushed it off. But then stranger, more significant things – like cherished ornaments on the Christmas tree – disappeared with no clear explanation. My older brother was but nine months old, so the most likely explanation – the kid had done it – held no water. As the tension torqued up, everyone said less and less – except for Gram – recognizing that just about any sentence could easily become a landmine upon which no one wanted to step.

The night of December 23, mom was awakened by scratching in the basement. She could not imagine what was happening, but tried to ignore it as sleep had become her sole respite. Next came a much larger clamor that she could not ignore; someone was in the basement – perhaps a burglar had broken in? Furious and exhausted, she grabbed her robe and headed for the stairs. The light was already on, which meant someone had turned it on at the top of the stairs. She crept down quietly and craned her head to see what was going on: there, in the center of the floor, stood Gram fiendishly ransacking Barbara’s boxes.

She was so enthralled in her theft that she didn’t even hear her daughter descend. She was shoving a small silver ashtray in her robe pocket, then something that looked like a little book or box. Here she was, plundering her daughter’s possessions. While it was altogether too much, it suddenly made very clear how she had wrangled all those new acquisitions. She really was just filling her shopping basket with stolen goods and passing them off as her own. While it sucked for Barb, this was not a battle she was willing to have with Christmas – and their departure – so near. She crept back up the (thankfully carpeted) stairs and returned to bed.

The next morning, nothing was any different. Gram was bellicose and belligerent; all was right with the world. The boxes in the basement had been returned to their original configuration so no questions would be asked, though God knows what all she had taken. Mom prayed for two things that morning: 1) that her father never find out about her mother’s thieving and 2) that Barbara not ask to go through her things. If either happened, the results, though undoubtedly spectacular, would almost certainly result in a burial of some sort – though whose is anybody’s guess. That was one basket she simply could not stand to see drop.

The holiday progressed like the nightmare everyone expected it to be. The entire family expended a great deal of time and energy not saying anything about Gram and Papa’s impending departure or any of the million other minefields someone might mention to trigger an explosion. Not that it helped; Gram found a way to fight even if nothing substantial was said. After a series of minor skirmishes over the modern state of marriage and how many more children my parents might produce, it seemed as though they might only suffer garden variety dogfights followed by seething silences.

When Papa expressed disappointment that mom had forgotten his favorite spiced peaches, Gram felt the footlights on her face: she was ready for her close-up. “Oh you want to talk about PEACHES, eh?” The look on his face made clear that he most assuredly did not, though he understood the question to be rhetorical. My father, never one to understand human facial cues or charged contexts, came to Gerald’s defense: “I love peaches! My mother used to put them up by the truckload. She made pies and cobblers and cakes – even sometimes pickles! And ice cream – oh, that ice cream! There wasn’t anything she didn’t do with those peaches.” Dad, usually silent to the point of catatonia, suddenly had something to say as everyone gaped at him in stunned silence. If Gram could have incinerated him with a scathing stare, they might all have started to believe in spontaneous combustion.

“Pat, do you remember the peach story?” he blundered forth. She knew a lot of peach stories, as it turned out, and none of them were appropriate for repeating. Rather than answer, she implored with her eyes that he shut the hell up. As far as anyone could remember, he hadn’t strung so many words together in one instance in the entire ten years they had known him. He always could be counted on to talk cars, everyone knew, so they assiduously avoided the topic and he avoided adopting other approaches – until the peaches, that is.

“You know, when I was in the service and you came down with Mom and Dad!” Now he managed to introduce his parents into the peril of the peaches, which only made things worse. Gram loathed his parents; everyone did. It was rare to have a holiday without them; conjuring up their specters only soured the situation further. Nevertheless, he persisted.

“It’s a great story. You have to hear it!” Though no one signaled they were prospective buyers for what he was selling, he barreled ahead. “You see my dad is really cheap – wouldn’t spend a dime for a safe seat in hell. And mom, well, she just loves produce. It makes her so happy to get as much fruit as she can to put up so that she can make all kinds of sweets for me and dad. It’s really her favorite thing to do.” Of course all of this just sounded like veiled criticism to everyone except dad. Helen hadn’t been the dream wife that Catherine apparently was; she had the nerve to resent all the damage her forced domesticity had done. Why couldn’t she just be like brainless, bullish Catherine who had dropped out of school in the eighth grade and boorishly boasted of having “never read a book”?

“Anyway, all the way to Fort Polk, mom kept seeing roadside stands selling peaches. She was so excited, you know, ‘cause she just LOVES peaches. ‘Don,’ she’d say, ‘we have to stop for peaches on the way back.’ Dad would just grumble, which she took was agreement, and she would talk about all the things she’d make with those peaches. Isn’t that right, Pat? Shouldn’t you tell the rest? You were with them, so you know it best.”

Now it was mom’s turn to fantasize about my father’s head in flames. He just couldn’t be stopped, stupid as he was. Rather than respond she just kept staring, uttering silent prayers that the whole house suddenly explode. Barb, who could not take any more tension – and who had heard this peach parable a half-dozen times before – absconded for the bathroom. And then there were four.

“Anyway, they’d all been in the car for days. Even when they got to Fort Polk Dad still insisted they sleep in the car. They had their usual three square meals of hard salami sandwiches smothered in Miracle Whip that they washed down with Dr. Pepper from the cooler. My folks love travelling like that – spent my whole childhood that way. I guess they were all a little tired, though, because the ride back was a little rough, right honey?”

Crickets.

“Anyway, Mom talked about nothing but those peaches. She was going to take home two bushel baskets of peaches and make preserves. After each peach-stand passed, Dad would say ‘at the next one,’ which Mom took to mean he would stop. He must have said it ten times, right?”

“I guess,” mom grudgingly granted, hoping to bring about some end.

“Anyway, the miles started to stretch and they stopped seeing peaches. Mom asked about circling back, but Dad just exploded. ‘Stop talking about those goddamn peaches, Kate! You don’t need ‘em,’ he bellowed and the rest of the ride home was silent. She never did get any of those peaches, which is a pity.”

The story’s conclusion was met with incredulity. He wasted his word allotment for the next decade on a story highlighting his father’s cruelty and his mother’s gullibility? Helen could relate and so she paid back his blathering with a contemptuous chortle and abruptly got up, knocking over her chair. If there were any justice in the world, a bewitched broom or enchanted chariot would have suddenly manifested and carried her away from that debacle, ideally as she cackled crazily. Instead, she choked out “Goddamn peaches, indeed!” as she started to sob. There was nothing else to say, so she retreated to her room to sleep.

Dad had no idea what he had done, though the three left at the table all sensed it was serious and understood that a counterassault would come. All was quiet on the sequestered front as Helen did not emerge from her room for the rest of the day. Mom kept sniffing for smoke, certain that her mother was about to Medea them at any moment. But nothing happened; the rest of the day passed unremarkably as they anticipated Gram and Papa’s departure for Illinois the following morning. They had only to get them to Stapleton by eleven and their responsibilities for a resplendent holiday would conclude. Hopefully they would find a house to rent, removing them from their children’s day-to-day life.

When morning came, Helen still hadn’t emerged. As everyone scurried about preparing to leave, she finally appeared in her housecoat. They should have known this was when she would make her stand; this had been her m. o. for as long as anyone could remember. As someone who rarely enjoyed the ability to exercise control over her environment, she learned to assert sway through intransigence. She simply would not be moved, literally or figuratively. She spent her days in a housecoat, forever in the process of getting ready and frequently failing to succeed. When she knew everyone else was waiting and expected her to hurry to catch up, she frequently sat down to compose a letter.

She had learned this strategy after a lifetime of being ignored and expected to perform and, for whatever reason, no one was capable of altering this particularly passive assault. “Mother,” mom said, “we have to leave for Denver in a half hour. You have to get ready now.”

“Not until I have my tea,” she said, heading for the kitchen. Uncertain of whether to tell her there was no time and risk another round of yesterday’s battle or whether to remain silent and hope for the best, Mom opted for silence. Helen set about making her tea and noticed Mom’s wedding band sitting on the window sill above the kitchen sink. In one swift motion, she slipped it into her housecoat pocket before anyone could notice. Every step and task to make tea was taken ploddingly as mom stared from the dining room. To complain would only compound the problem.

After tea was taken, there were about ten minutes left before they needed to leave. They would not make the plane, Mom felt certain. Forty minutes later – which was still a minor miracle – Helen announced she was ready to leave. She asked Dad to collect her bags, unnecessarily stating that she would collect her red bag herself. When she emerged minutes later, bag on forearm, the glass basket’s handle peeked just above the brim. As she caught Mom eyeing it, she felt a surge of satisfaction. Would she confront her here? Did she dare call her own mother a thief?

Intent upon departure, Mom refused to be goaded. Let her steal the basket. She didn’t care what happened to it; Barb could always get another. As they piled into the station wagon, snow started to fall and they all knew for certain the trip was pointless. Nevertheless, they forged ahead. Dad drove ninety miles an hour down I-25. Helen was suddenly chirpy and full of excitement about Illinois and returning home where “people love her.” They would stay with Gerald’s brother, Jim, and his wife, Lois, when they arrived. Once a house had been located, my parents would drive back with their household goods. Helen felt certain they would return to their church and catch up with all their friends; life would become what it had once been – at least in some fashion.

Much like their ill-fated flight, however, it was not to be. They would all return to Fort Collins that day, though not before Helen managed to drop her cranberry glass basket on the concourse floor as they attempted to run to the gate. She could not move that fast – her peach injuries being the primary cause, along with her excessive weight – and though she tried, she managed to tilt her bag forward just enough for the basket to tumble out. As it made impact, the shattering silenced everyone around them. Gerald simply stared at his wife with contempt, but said not a word. “What the hell are you doing with that?” was written all over his face. There was no time to ask or explain, they just kept moving instead.

In the post-holiday airport rush, this incongruity got swallowed up in the throng, though it no doubt made an impact. Helen, in all their estimation, was officially a basket case – if one understands the word in the colloquial sense that means crazy. The word itself has a darker, more painful meaning coined for the poor souls who lost all their limbs in the First World War, but no one seems to remember that anymore. Nevertheless, she may even have thought of herself as such since she often used the word herself as a synonym for crazy. She had become the sort who explodes and steals, nursing painful wounds that would never heal. Whereas anyone else might have been humiliated by that broken basket, she brushed it off as though nothing had happened.

It was all a challenge: would they confront her? Did they dare ask how she could do such a thing? She thought not. For years she had been a wife and a mother – a person with prescribed roles she was expected to perform without complaint or complication. By and large, they didn’t care what happened to her, she thought, she was merely a perfunctory placeholder useful for her services – especially when she managed not to harm herself or expect anything in return. Henceforth, she would be relegated to the role of basket case. She would push boundaries and challenge convention; she would revel in their refusal to address her audacity. They had all but used her up, she thought, and now she would show them that she could not be controlled or made to feel guilty. Their resistance to listening to pain and disappointment meant that things like stolen baskets shattering on airport floors had to be treated as commonplace, unworthy of mention. They would be forced to pretend they found her crazy quotidian.

And mostly, they did. Oh sure, among themselves they commiserated about how crazy and unpredictable she had become. There were dark whisperings about her drug use and endless theft. They feared, though, that to confront these issues would only inspire worse behavior and so they opted to ignore it as much as possible. My father bought Mom a new wedding ring since she announced that his peachy story had led to its theft. My grandparents did finally return home and Helen was even more free to commit theft at every turn as my grandfather pretended his cataracts precluded catching his predatory partner in the act – even as she boosted more baskets to keep as badges of her defiance.

JOSHUA G. ADAIR is an associate professor of English at Murray State University, where he also serves as coordinator of Gender & Diversity Studies. His work has appeared in over fifty scholarly and creative writing journals, and his collection Defining Memory: Local Museums and the Construction of History in America’s Changing Communities (edited with Amy K. Levin) appeared from Rowman & Littlefield in 2017.

“To Helen, a Handbasket” is part of Adair’s forthcoming book, The Kleptomaniac’s Collection.

Featured image: Paul Gauguin, “The Siesta,” oil on canvas, ca. 1892-1894, The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection, Gift of Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, 1993, Bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.