Memoir writing can be terrifying. Having it read can be worse. It can also be deeply satisfying. That look into the interior can produce both soothing revelations and dredge up uncomfortable monsters. But the fear is necessary. Without it, the writer lacks the alertness and sensitivity to produce meaningful work. And without readers, the writer remains forever alone.

That is part of the beauty of all literature. You discover that your longings are universal longings,

that you’re not lonely and isolated from anyone. You belong.

– F. Scott Fitzgerald –

Memoir is like a dangerous surgery, turning the body inside out. It reveals the organs, blood vessels, and the nerves. It exposes them to the world and as writers peer into their own inner workings, readers peer inside, too. And that is terrifying. Writing about the personal is not for everyone. Most memoirists come to the genre not because they dream of exposing their personal and private selves for all the world to comment on but are motivated by a deeper need—to understand an experience, to remember a great love, to find closure for grief. The reasons are many, but we engage in the fear of writing memoir to feel we are not alone.

For most of my life I had no idea I wanted to be a writer, even though I spent hours as a kid writing songs and poems on computer paper. It should have been a clue to me that writing was in my future the way I talked and talked and talked. It wasn’t just my mother who I wearied, but my brothers and sisters and aunts and uncles and cousins and neighbors and store clerks and librarians and even the Jehovah Witnesses, who came to our front door with their pamphlets, eventually became exhausted from my endless chatter and hurried down the porch stairs while I leaned after them trying to finish my sentence. Whether written or spoken, words to me, were more than just letters rearranged into myriad combinations. They were chemical components, inert on their own but powerful and sometimes unstable when combined. A word could become anything, sometimes a tonic, sometimes a sword. Words could be subtle, like a barely felt breeze or they could suck your breath out of your body, loud as a tornado. But words were always alive. And I wanted to wield them. And when there was no one else to talk to, I wrote words on every sort of surface, leaving cryptic messages on doorframes, inside of wooden dresser drawers, scratched onto exposed water pipes in the basement.

I had no idea I wanted to be a writer, but I did know I loved words. Words helped me navigate a childhood fraught with danger. Words helped me contain the rage that might have turned to violence. Words helped me stitch up the emotional wounds that otherwise might have become septic. When I became aware of the lack of tolerance of others for my longwinded musings, I turned more and more to the solace of writing. And certainly no one seemed to care how many volumes of spiral bound notebooks I filled up. I talked less and less and wrote more and more. I didn’t censor myself for fear of what others might have said or thought precisely because I had no idea I wanted to be a writer. There was great freedom in that ignorance.

I remember, as a girl, sitting at the third-story upstairs bedroom window with my pen and paper determined to write a poem. I was eye level to treetops and telephone wires, and the small birds that flew so close I could hear their wings like short exhalations. It was evening, and the sky was impossibly blue, contrasted by the pale, pink light of the fading sunset. My view was overlaid with tree branches and the jutting shapes of rooftops and chimneys; swamp coolers and TV antennae. I wanted so badly to write what I saw and felt, sitting above the world that way. Even though I was aware I would be disappointed in the poem, I wrote it anyway. I was trying to pin down a specific moment to hold it in place, and I had to give it my best attempt. I wanted to use the poem as a time-traveling device. To go back and feel all those sensations again, to see the picture I had taken with my language camera, and to sit at that window on that night again, and again—any time I needed to.

And it worked.

Here I am some thirty years later, the scene vivid and clear, the feelings and thoughts of that young girl are all right here at my fingertips. I don’t have the poem anymore, it has been lost among the thousands of others I wrote that disappeared into packed boxes and folded up yellow envelopes. The only part I remember was using the phrase azure sky and how my pulse quickened every time I read it. Azure sky. Azure sky. (The right word can feel so satisfying!) It was a terrible poem, I am sure of it. I did not have a gift for precise, poetic language, but I had a yearning to turn life into art, to convert my experience and emotions into a something I could fold up and put into my pocket for safekeeping. That drive is what kept me writing awful poem after awful poem. It inspired a poem about a made-for-TV movie in which I swooned over the male actor, to the comic family epic that rambled seventeen pages long. I wrote silly, little sonnets about the moon, the stains of oil on the driveway, the little rosebush growing in the front yard. (Actually, I had no idea what a sonnet was, I just called them sonnets so I would sound sophisticated.) I conducted written interviews with my brothers and sisters, always referring to myself as a journalist, pen tucked seriously behind my ear with notepad always handy for those impromptu interrogations about their views on bedtimes and other unfair household rules. I had a few long-distance friends to whom I regularly wrote epistolary volumes about my thoughts on every imaginable topic that were so many pages long I could hardly stuff them into an ordinary envelope. I kept journals through the years, a catalogue of the ranting and ravings of a teenager, full of code words and vague references I thought I would remember for the rest of my life but didn’t.

And yet, I had no idea I wanted to be writer. What I did know was I wanted to understand myself and others, to express the intangible into words. Like a magician, I wanted to step into the invisible world of feeling, thoughts, and mood, and call forth heroes and monsters alike. To use words to weave a magical carpet, to turn lead into gold, to open caves of treasure, and to break evil spells cast upon the innocent.

When I finally realized I wanted to be a writer, I had already been writing for a very long time. Wanting to write and wanting to be a writer are two very different motivations. As a child, I wanted to write, and with nothing more than a pencil and paper I was able to fulfill that desire. As an adult, I wanted to be a writer, and found myself frustrated by the longing to release and the need to be validated by others. Writing had always been a private, internal experience. Wanting to be a writer required me to step out of the comfort of the self. It meant being read. Having my writing read meant having it judged, evaluated, analyzed, criticized, or praised, valued, respected, and even distributed. I was in my mid-twenties when for the first time I experienced the blindness that comes from staring directly at the whiteness of the blank page. I wrote and erased. I wrote, and then refused to let others read my work while also dying to have someone read it and tell me it was okay. I wanted someone else to tell me that I was okay.

I wasn’t afraid of writing. I was afraid of the written. I wasn’t afraid of the process of writing, I was afraid of the product. The process was all possibility. The product had edges and boundaries. It had a beginning, middle, and end. It proclaimed itself. It was at those very edges I met my fears. What was once so effortless became paralyzing. While I was drawn to the process, I panicked at the product. It is why I find endings so difficult. It is a door closing. It is a proclamation that what I have written is enough. I am proclaiming that as a writer and even as a person, I am enough.

The fear is real. To mitigate this fear, I tried to be objective in my writing. I tried to reduce it to a formula or a recipe, like baking a cake or weeding a garden. But when I did this, my writing was empty and lifeless. It needed the uncertainty and risk of failure to keep it alive. It is also exactly what is required to create compelling work. It is this fear that keeps the work dynamic and vibrant. It is fear that pushes me, challenges me, and asks me to move nearer to the edge. It reminds me there is always more to learn and that not everyone will approve of what I have to say, but that doesn’t make it any less necessary to say it. It requires me to take responsibility for my words, even if I am frequently surprised by them. As a writer, I feel both competent and utterly incompetent at regular intervals, sometimes simultaneously. And, like all works of art, the written can never truly be finite. It is a prism, a container to hold a living idea that can be returned to again and again, allowing the reader (and the writer) to discover something new each time.

Memoir, especially, has the audacity to slice through skin and bone and enter our hidden human spaces, allowing the writer, with gloved hands, to touch the delicate memories, the framework of experience. When I allowed others to read my work, what I thought was mine alone—my brokenness, my shame, my hope—became our brokenness, our shame, and our hope. Ours.

SUSANNA BARLOW is a full-time writer. Her memoir Not in My House is about her life in a polygamous family and how she overcame the struggle of surviving abuse. It won First Place for Creative Nonfiction in the Utah Original Writing Competition 2017. An excerpt of her book was published in Artists of Utah 15 Bytes in 2018. She enjoys helping other writers with one-on-one writing guidance and as a developmental editor. You can find her online at susannabarlow.com and on Twitter.

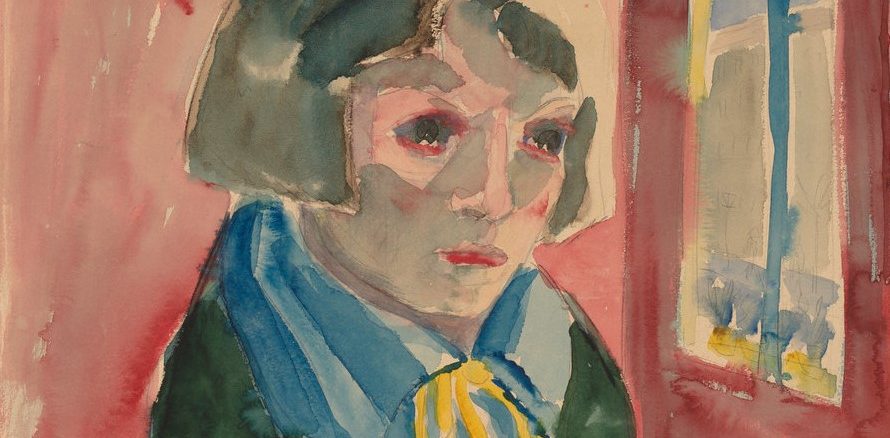

Featured image: Walter Gramatté, “Woman at a Window,” watercolor over graphite, 1922, Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen, National Gallery of Art.